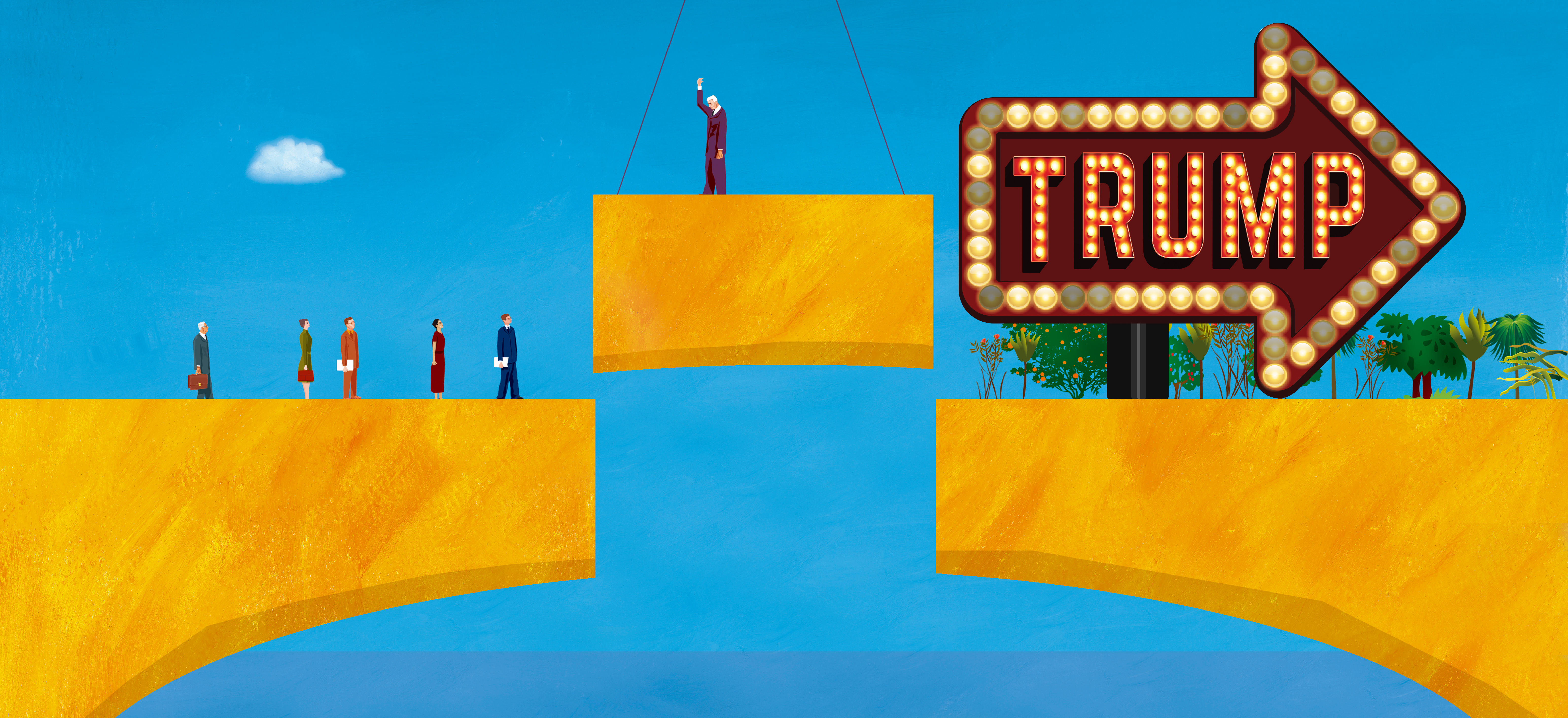

Mike Pence has a bridge to sell you

The GOP vice presidential nominee is building a bridge between Trumpism and the Republican Party

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The vice presidency is a transparently stupid office.

The only reason we have a vice president in the first place is that the presidency was originally conceived as a kind of elected monarch chosen by the people from among the national worthies. Within such a scheme, it wasn't completely silly to designate the runner-up as the successor-in-waiting — which is how our presidential elections worked in the early days of the republic.

But soon enough, it became clear that elections for president would be partisan affairs, so it stopped making any sense for the vice presidency to go to the runner-up. The job of serving as a political sop to a losing faction and waiting for one's predecessor to die is a poor fit for anyone temperamentally suited to the presidency. And so for much of the rest of American history, the vice presidency was a thankless office, and most of those accidentally elevated therefrom have distinguished themselves primarily by their mediocrity, and occasionally by worse.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It would have been preferable if the framers of the 12th amendment had eliminated the office entirely, and designated the secretary of state as successor in the event of the death, impeachment, or resignation of the president, with a special convention of the Electoral College to follow either to ratify or to replace the accidentally ascendant. Alas, that is not what happened.

Which brings us to 2016.

Hillary Clinton is an establishmentarian candidate par excellence, and her running mate is cut from closely matching cloth. How Tim Kaine comports himself in a debate or on the hustings is of interest primarily to people curious about the possible political future of Tim Kaine, either in four years if Clinton loses or in eight if she wins.

Mike Pence is another story. As a highly orthodox and thoroughly boring VP nominee, the sort of person who one can imagine being president but have a hard time picturing getting elected under his own power, his selection bares some resemblance to Ronald Reagan's choice of George H. W. Bush in 1980. He represents almost perfectly the party that existed prior to Trump's triumph. By accepting a spot on the ticket, then, Pence has positioned himself uniquely as someone who could attempt to bridge the gap between the conqueror and the conquered.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Tuesday's VP debate was our first glimpse at how that gap might be bridged. But to see it clearly, we have to see past the smoke screen that Pence emitted for much of debate.

That smoke screen was a consistent effort to pretend that there was a clear thread of continuity between Trump and prior Republican history. Pence simply refused to acknowledge that Trump represented anything particularly new, except in personality terms. This has been described variously as a gaslighting of the American public, as a form of political performance art, and as possible further evidence of the strength of conservative epistemic closure.

But if you set aside the fact that Pence egregiously misrepresented Trump, and consider merely how he represented him, you can see the outlines of Pence's bridge between Trumpism and the GOP. Here's what it looks like.

1. The Anchorage

In suspension bridge construction, the anchorage is the heavy, solid structure at either end of the bridge that holds the tension of the cables. And there are analogously solid ways in which Trump does represent conservative Republicanism as we have come to know it. Trump has proposed a massive tax cut tilted overwhelmingly toward upper income taxpayers. He has proposed a wholesale gutting of regulations aimed at environmental and consumer protection. He has called climate change a hoax. He has loudly proclaimed his allegiance to the NRA's understanding of the Second Amendment. And while he patently has no interest in religious or moral conservatism, he pays lip service to the idea of appointing judges approved by the socially conservative right.

Finally, Trump is a walking, talking affront to political correctness in all its forms. Inasmuch as that's a real motivating issue for Republicans (and it appears to be), it's hardly one that began with Trump.

Pence comfortably hit all of these themes in the debate, and he could do so without completely denying reality. If he was speaking to Republicans reluctant to make their peace with Trump, this was the anchor of that appeal.

2. The Span

Two of Trump's signature issues, immigration and trade, are areas where he has forthrightly flouted recent Republican orthodoxy. But these are issues where the Republican Party has been engaged in intramural squabbling for some time. Much of the congressional GOP has been in open revolt against the party leadership over immigration reform since the second term of George W. Bush's administration, and heterodoxy on free trade has been on the rise within the GOP — indeed, even an establishmentarian former investment banker like Mitt Romney saw fit to attack China for predatory trade practices during the 2012 campaign.

It's not particularly clear what Trump proposes to do about America's trade deficit or about the precipitous decline in manufacturing employment. Much of the damage from the rise of China has already taken place, and most of it isn't due to currency manipulation. But what is clear from the debate is that Pence — a Midwesterner — is more than willing to highlight trade as an issue for the future. “Deals that put the American worker first” will be the watchword — whether the deals themselves actually do that or not.

Similarly, with immigration, Pence soft-pedaled Trump's more extreme proposals (the formation of a deportation force, for example), while staking out a position that is still considerably more restrictionist than the Bush-McCain-Rubio view. After 2012, the quick consensus was that the only way for the GOP to win the White House in the future was by spearheading immigration reform. Pence's comfort speaking about immigration almost exclusively in terms of security suggests that at least some of the establishment isn't eager to be trumped on this issue again — even if they aren't quite willing to be as vituperative as their nominee.

3. The Suspension

Trump's third signature issue in the campaign has been foreign policy. He started by vocally criticizing the Iraq War, which he claims to have opposed from the beginning (and which his Democratic opponents claim he supported — though the likely truth is that he never really thought about it at all). But his critique spread far beyond Iraq, to question the very basis of collective security itself. Trump's vision of American foreign policy is far from coherent, but its impulses are narrowly self-interested. He has proposed unilateral actions in violation of both international law and the laws of physics to crudely advance American goals, construed alliances as a tributary arrangement where clients pay us for protecting them, and expressed blithe unconcern about the possibility of the world being reordered by other powers in ways that might ultimately be detrimental to America. This vision is completely at odds with the notion of America as "leader of the free world" or the guarantor of international order.

On this subject, Pence flatly ignored the unbridgeable divide between his own views and those of his boss. Pence argued for a more aggressive approach to the conflict in Syria, a conflict which Trump has said America should let Russia handle (apart from bombing ISIS and somehow magically taking their oil). He argued for a more confrontational policy towards Russia in its near-abroad, something Trump has explicitly abjured. Faced with Trump's insouciance about nuclear proliferation and his proclamation that NATO is obsolete, Pence behaved as if Trump never said these things.

Pence could have presented a more rational, reasonable Trumpism, calling for a more cordial relationship with Russia or a less-hegemonic approach to the Middle East without abruptly tearing up existing commitments. But he did nothing of the sort. Whether Pence genuinely can't tell that Trump's views are wildly at variance with what GOP candidates have stood for in the past, or whether he thinks Trump's voters are unaware of the ways in which he has broken with that tradition — either way, his determination to stick to the old script suggests that this divide will be bridged only by a flight of fancy.

Or perhaps after four years of governance by a liberal hawk, even the GOP establishment will have to consider whether it might not be worth considering alternatives to omni-belligerent "leadership."

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.