I want Hillary Clinton to win Texas and Donald Trump to win Wisconsin. Here's why.

Donald Trump needs to lose the election — bigly. But if he wins certain swing states, both parties will learn important lessons.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Assuming the polls are not wildly off, and that nothing dramatic radically changes the outlook for the election, Donald Trump is going to lose, and lose badly. And if he loses badly enough, he may drag the Republican Party down with him, costing them control of the Senate and leaving the House on a knife's edge.

Such a rout would be richly deserved. But there are different ways for the GOP to lose badly, with different implications for the future. A double-digit victory margin for Hillary Clinton, and an overwhelming, 1988-style victory in the Electoral College, would be a clear repudiation of Trump and all he stands for. But that's precisely the problem. Not all that Trump stands for deserves repudiation, but a devastating loss of that sort would encourage the Democrats to consolidate their newly dominant coalition, while encouraging the Republicans to return to their old time religion in the hopes of restoring their brand. Such a "reset" of American politics to its pre-Trump configuration would leave the crucial issues Trump raised unaddressed.

An Obama-style victory would, in some ways, be even worse. If Trump is able to hold on to the states Mitt Romney won, in spite of Trump's manifest unfitness for office, his open warfare against his own party, and the hollowness of his own campaign, the message to Republicans will be: Our base is impregnable. We don't need a positive message; we just need for the Democrats to fail and a working majority will fall into our hand. And that failure is only a matter of time.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

A nail-biter, meanwhile, would be the worst outcome of all, empowering Trump personally to pursue his claims that the election was rigged, and to remain the voice of much of the GOP's base, while turning the focus of both parties' attentions toward the personal weaknesses of Hillary Clinton.

No, what the country needs is a clear and decisive repudiation of Trump that also demonstrates that his message struck a chord beyond the precincts of Appalachia — a victory for Clinton that also contains a warning about the dangers to come if Trump's legitimate issues are not addressed, and a loss for Republicans that also points to a more promising future under a different standard-bearer.

For a model of what such a loss would look like, consider not the blowout elections of 1972 or 1964, but the election of 1896.

For the 20 years prior to that famous election, the Democrats had done moderately well for themselves by nominating moderate candidates from the mid-Atlantic states (Samuel Tilden was from New York, as was Grover Cleveland; Winfield Scott was from Pennsylvania). They won some elections, and they lost some elections — and when they lost, it was by the narrowest of margins (indeed, they twice won the popular vote but lost the Electoral College).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

But there were unaddressed issues bubbling that threatened the stability of the parties as they stood. In particular, America's farmers were suffering severely under the prevailing hard-money policy that President Cleveland's Democrats shared with the Republicans, and there was a pervasive anxiety about how mass immigration was changing both the character of the country and the distribution of the era's economic gains.

In 1896, the Democrats broke with what had been their winningest formula, and nominated a populist champion, William Jennings Bryan. Bryan ran on a platform of bimetallism — an inflationary policy that would help indebted farmers at the expense of creditors — and against the banking interests on the East and West Coasts. And he personally represented a notion of what a "real American" was, or ought to be: white, Protestant, and oriented toward the countryside.

Bryan lost — and lost decisively. But he also won states that no Democrat had won since the Civil War — Kansas, Nebraska, and Colorado — along with new states like Washington, Montana, and Utah. Bryan gave representation and a voice to those who were losing ground in the era of the robber barons. And while McKinley's coalition was the coalition of the future, a version of Bryan's coalition — one that more comprehensively added Northern industrial workers — represented the future of his party.

Today, America's industrial laborers are in a somewhat analogous position to farmers in Bryan's day. And while Trump is no Bryan, his explicit appeal to those voters, and declaration that he would be their voice, deserves electoral recognition. Both parties need to be put on notice that there is a set of voters, and a set of issues, that are up for grabs, and that there is opportunity as well as risk involved in courting them.

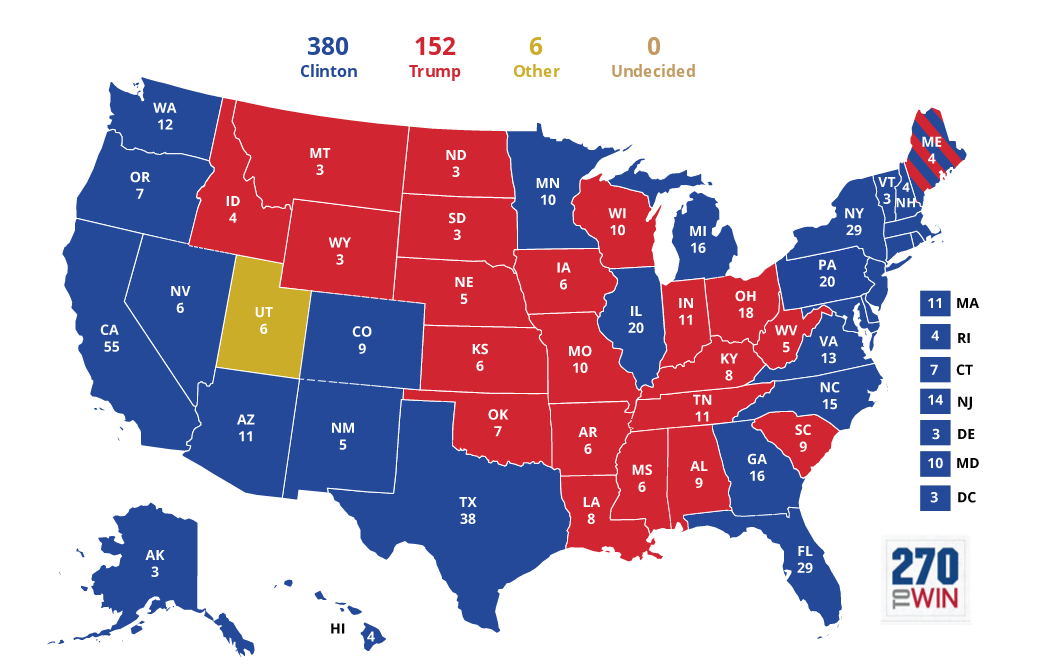

So if had my druthers, on Nov. 8, the map will look something like this:

Is that map even possible? Could Clinton win Arizona and Georgia — even Texas and Alaska — while losing Ohio, Iowa, and even Wisconsin?

It's not likely — but it is possible. Clinton hasn't led in any recent Texas poll, nor Trump in any recent poll of Wisconsin — but several polls of each state show the race in the low single digits. And the likely electoral drivers in each state are demographically quite different. Clinton could win Texas with massive Hispanic turnout in cities like San Antonio coupled with large-scale defections from the GOP by educated white women in suburbs like Plano. By contrast, if Trump were to win Wisconsin, it would be because he racked up huge margins among white voters without college degrees in places like Racine who traditionally have voted Democrat, if they voted at all. As for Iowa and Ohio, they have seen quite a number of polls that look promising for Trump — about as many as Arizona has had that herald a Clinton victory.

If I were a senior Democratic Party official and saw that map, I'd worry about 2020. I'd know that a less personally repellant nominee could bring states like Texas and Arizona back into the fold, and that a GOP that put some substance behind some of Trump's gestures towards economic populism could be a major threat across the Great Lakes. Throw in a recession, and Clinton becomes a one-term president. And so I'd caution Clinton to remember the mantra of her husband's campaign — it's the economy, stupid.

And if I were a senior Republican Party official and saw that map, I'd be chilled by the political abyss that a continued embrace of Trumpism had opened up. But I'd also be warmed by the promise of a future beyond 2020 — and I'd see that map as the opportunity to engage in the vigorous debate about the party's future that the leadership had assiduously avoided for three cycles.

It's not likely. But wouldn't it be nice if this stormy electoral season ended with a silver lining?

Noah Millman is a screenwriter and filmmaker, a political columnist and a critic. From 2012 through 2017 he was a senior editor and featured blogger at The American Conservative. His work has also appeared in The New York Times Book Review, Politico, USA Today, The New Republic, The Weekly Standard, Foreign Policy, Modern Age, First Things, and the Jewish Review of Books, among other publications. Noah lives in Brooklyn with his wife and son.

-

‘The West needs people’

‘The West needs people’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxes

Filing statuses: What they are and how to choose one for your taxesThe Explainer Your status will determine how much you pay, plus the tax credits and deductions you can claim

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred