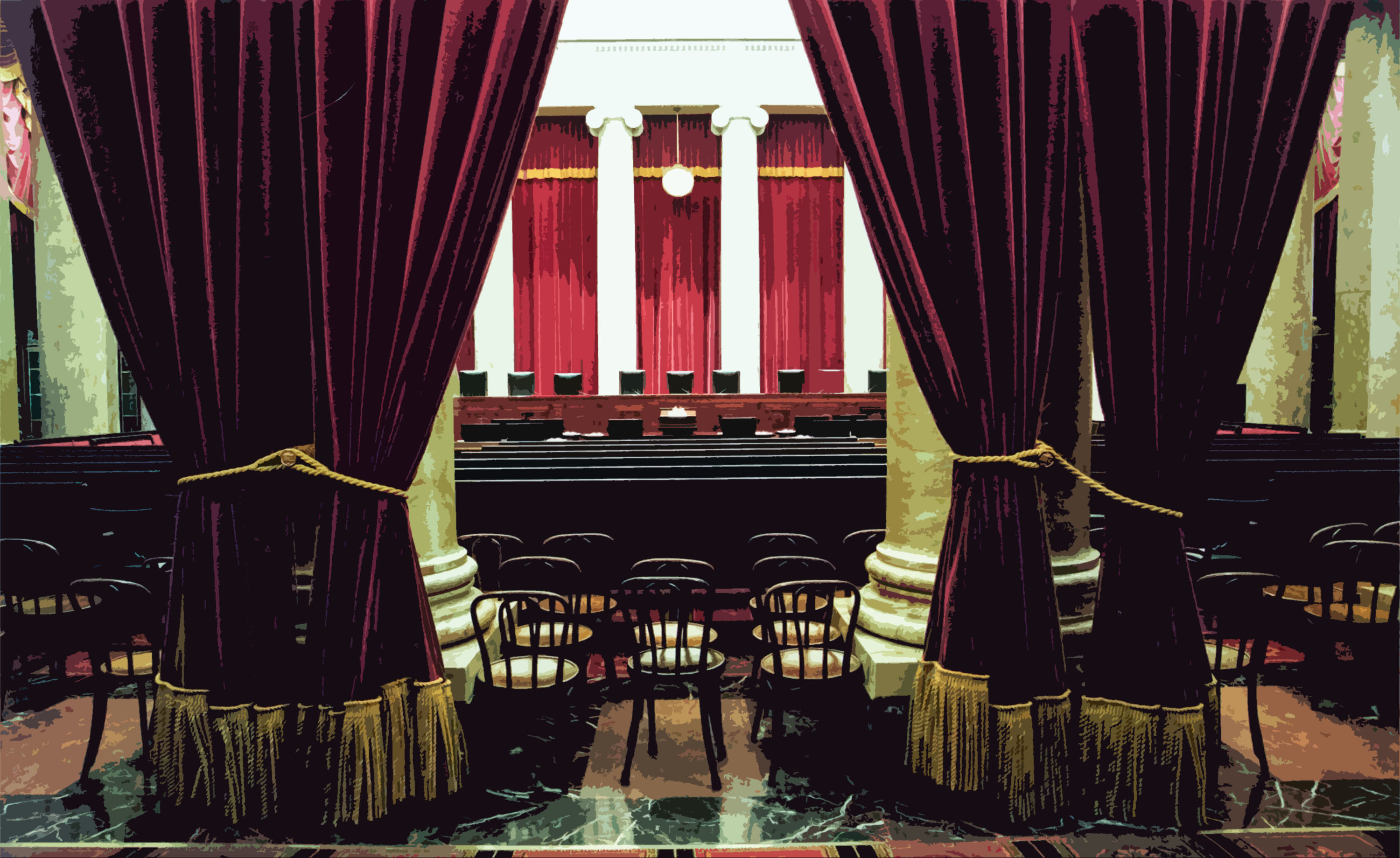

How to fix the Supreme Court

Supreme Court justices shouldn't serve for life. They should each get 18 years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

America's severe partisan polarization is wreaking havoc on each of the branches of the federal government. But it's the judiciary that's so far suffered the gravest consequences.

In the year since the death of Antonin Scalia, the Supreme Court has been hobbled, forced to muddle through its tasks with just eight justices. The proximate cause of the problem was, of course, the refusal of the Republican leadership in the Senate even to hold hearings, much less permit an up-or-down vote, on Merrick Garland, President Obama's choice to succeed the conservative justice. That, in turn, has inspired Senate Democrats to refuse to meet with Neil Gorsuch, President Trump's nominee. If the Democrats attempt a filibuster, the Republicans will be able to use their majority to force a vote by changing the rules of the Senate. That would mark yet another new low in the politicization of the high court.

The rancor embroiling the court is an expression of broad-based polarization in American political culture. But when it comes to the court itself, this hostility ultimately traces back to 1987, when Senate Democrats rejected the nomination of Robert Bork purely on ideological grounds. Tensions surrounding the confirmation process for federal judgeships and the high court have slowly increased ever since then, with the Garland blockade setting a new standard for dyspeptic dysfunction.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Republican Mitch McConnell, the Senate majority leader, claimed there was precedent to block a high court nominee in an election year, but it wasn't true. Instead, what we saw in the unparalleled intransigence of the Republicans was an expression of ideological desperation: If Obama were permitted to flip Scalia's seat to the left, it would be a net ideological gain for Democrats — and the stakes were simply too enormous to permit that, especially with a presidential election looming.

Whether McConnell would have permitted an Obama nominee to receive a floor vote if Scalia had died three months earlier — a full year before the presidential election — is something we will never know. The same goes for the possibility that McConnell or other Senate Republicans would have blocked any and all nominees named by a President Hillary Clinton, as some (in the weeks leading up to Election Day) suggested they would do following the inauguration of the Democrat.

The stakes for both Republicans and Democrats are somewhat lower now. President Trump has nominated someone quite ideologically close to Scalia, making the Gorsuch confirmation a battle over whether the high court will be permitted to keep its former balance of liberals and conservatives. Yet Democrats remain understandably irked by the way Garland was treated and eager to inflict pain on Trump's nominee in retribution.

And then there's the question of what will happen when and if Trump gets the opportunity to nominate someone to succeed a liberal justice. Without the filibuster, there's little the Democrats would be able to do — as long as they continue to find themselves in the minority in the Senate. And that points to the possibility that we may have entered an era in which presidents are able to get Supreme Court nominees confirmed only when their party holds the upper house of Congress.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Thankfully, there is a possible way out of the ever-worsening deadlock that confronts us — an institutional fix that was suggested in a recent book by legal journalist Lincoln Caplan, American Justice 2016: The Political Supreme Court (which I had a hand in publishing).

Caplan proposes that the Constitution be amended so that Supreme Court justices are appointed for 18-year terms instead of life terms, with appointments staggered every two years. This would guarantee that each one-term president would get to nominate two justices, and every two-term president would get to nominate four, with the justices rotating off the court in a regular pattern every two years (except in cases of untimely death or debilitating illness). Caplan also suggests that the chief justice could automatically be the most senior justice on the court or the median justice — any mechanism that would avoid the arbitrariness of one nomination (immediately after the retirement or death of a chief justice) carrying more weight than others.

As Caplan notes, this reform of the court would likely "reduce the strife in the confirmation process, by making appointment and confirmation an every-other-year practice." And unlike most proposals for constitutional amendments, this one would benefit both sides of our polarized ideological divide. It's hard to see why either party would stand against it. It's fair.

Everyone has an incentive to de-escalate the high court wars. What better way to accomplish that worthwhile goal than to introduce a novel bit of institutional machinery into our 18th-century anachronism — the clanking and grinding Rube Goldberg contraption we call the Constitution?

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred