America needs more congressmen. Hundreds and hundreds more congressmen.

Engorgio Congress!

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pretty much everyone hates Congress. So it may surprise you to hear that we need more congressmen. Hundreds and hundreds more congressmen.

I have argued before that as long as the GOP remains in thrall to partisan extremism, the Democrats must use procedural warfare — within the bounds of the Constitution — not just to reclaim power over the next four years, but also to remake the American political system once they have attained it. That system as it exists comprehensively disadvantages Democrats in national elections and governance. Finding remedies for this problem means pursuing statehood for D.C. and Puerto Rico, enacting a huge expansion of voting rights and access, and breaking California into as many as seven different states, most of which can be achieved with simple acts of Congress and none of which require amending the U.S. Constitution.

But when they find themselves back in the majority, Democrats must also pursue an idea that might seem totally insane: Doubling the number of seats in the U.S. House of Representatives.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The GOP-led 2010 gerrymander was a fiendishly clever operation that handed the House of Representatives to the Republican Party seemingly in perpetuity. But even if Trumpian incompetence leads Democrats to recapture power at the state level in 2018 and 2020, and thus have the opportunity to strategically craft the next round of congressional redistricting, they have a major problem. It's called "partisan sorting" — meaning Democrats increasingly live together in major metropolitan areas while Republicans are concentrated together in the country's exurbs and rural areas. This is a problem not just for our politics — since individuals with opposing views rarely meet or interact with one another any longer — but for Democratic hopes of holding the House long enough to make real changes.

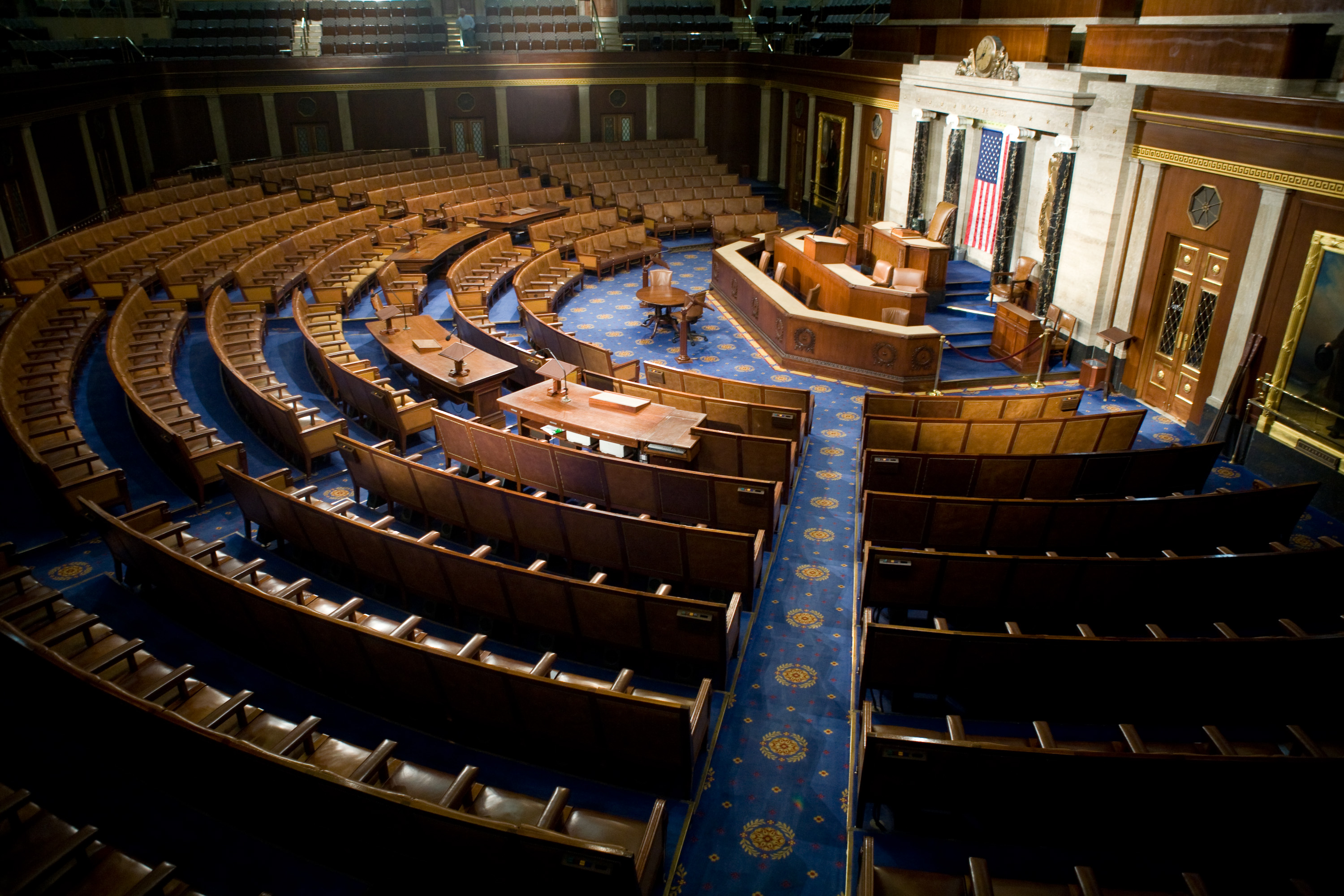

Is expanding the House even possible? Sure it is. Remember, many taken-for-granted features of our politics (like the size of the Supreme Court) are not written into the Constitution. One of those quirks is the size of the U.S. House of Representatives, which has been fixed by law since 1911 at 435. Not only does this set-up deprive most Americans of any meaningful access to their representatives, it is utterly in contradiction with what the Framers intended. In Article 1, Section 2, the Constitution states the "number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty thousand." Today, each House member represents, on average, more than 700,000 citizens.

In the past, Congress would routinely vote to expand the number of House seats to keep up with America's growing population. But this practice came to a sudden halt in 1911, when lawmakers worried that allowing the House to get too big would make governance impossible. Since then, the country has added more than 200 million citizens to its population but has never permanently increased the size of the House (the number was briefly upped to 437 when Alaska and Hawaii were admitted to the union). The U.S., in fact, features the second-worst legislator-to-constituent ratio in the entire world next to India. And unlike changing the makeup of the profoundly undemocratic Senate, there is nothing in the Constitution to stop Congress from scrapping its 106-year-old cap on the House and increasing it in size.

There are solid reasons for doing this just on democratic legitimacy grounds. Adding representatives in the House would give more ordinary Americans the opportunity to run for office and diminish the power of dark money on any individual race. Constituents would not need to travel as far to visit the office of elected representatives, whose staffs would have more time to devote to services. Most Americans have no idea who their representative even is — bringing that person closer to the people can only enhance his or her legitimacy. We'd have some bigly construction work to do on Capitol Hill to make room for the extra congressmen, but hey — this is the most powerful nation in the history of the world we're talking about here. We can build an addition on one of our houses.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Doubling the size of the House would also greatly benefit the Democratic Party, which suffers disproportionately from the concentration of its voters in major cities. Think of a state like Pennsylvania, which today is almost equally divided between Democrats and Republicans. Donald Trump won the state — which went Democratic in every other presidential election since 1992 — by the tiniest of margins. Yet this sharply divided commonwealth features an insanely gerrymandered House delegation of 13 Republicans and five Democrats, thanks to a combination of clever Republican-led redistricting after the 2010 census and the concentration of the state's Democratic voters in Philadelphia and Pittsburgh.

If Pennsylvania had 36 representatives instead of 18, it would be much harder to cram Democratic voters into overwhelmingly partisan districts in its two urban centers. Imagine, for a moment, that every single one of the 12 million or so citizens of Pennsylvania got a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. That delegation would by definition be impossible to gerrymander, and you would expect about six million Democrats and six million Republicans. The smaller the House delegation is from any state, the easier it is to manipulate the district boundaries to trap your opponents in a small number of overwhelmingly safe seats. And like all Americans, Pennsylvanians deserve a congressional delegation that represents their will rather than grossly distorts it.

The national implications of gerrymandering are clear and deeply problematic. In 2012, for instance, Democrats won more votes for the U.S. House than Republicans but received only 46 percent of the seats in the chamber. In 2016, Democrats lost the national House vote by a single percentage point but scored just 44 percent of the seats. The lack of fit between the national House vote and the number of seats has been a persistent problem throughout U.S. history. And before GOP partisans dismiss the idea, please note that Republicans have been on the wrong end of things as often as they have benefited from it. To name just one example, in the 1992 national election, Republicans received 45 percent of the House votes but received just over 40 percent of the seats. In fact, if Democrats lead the next round of redistricting, it will almost certainly be the GOP that suffers.

Like so many of America's democratic institutions, the structure of the House is an ossified relic unsuited for modernity. It just so happens that bringing the legislature into the 21st century would benefit today's Democrats. Sometimes self-interest lines up neatly with the right thing to do. Democrats would do well to start workshopping enlargement proposals now, so they aren't caught flat-footed the next time one of their own holds the speaker's gavel.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred