This is what it's like to have a president utterly devoid of empathy

Trump went all the way to Puerto Rico to talk about how great he is

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Have a good time."

That's what President Trump told a family of hurricane victims on his visit Tuesday to Puerto Rico. In fact, it wasn't the first time he offered survivors of a natural disaster his best wishes for a fun afternoon. As he was leaving a shelter in Houston for those displaced by Hurricane Harvey, he told the people there, "Have a good time, everybody." Have a good time.

This week we're seeing, more than ever before, what it's like to have a president who is not just utterly devoid of empathy, but unable to even pretend otherwise. Much as I hesitate to make a psychological diagnosis of the president, there is a void in this man where the ability to make human connections is supposed to reside.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At some point or other — and usually with regularity — the president of the United States is going to have to act as consoler in chief. There will inevitably be natural disasters, terrorist attacks, mass shootings (our particular specialty), and various kinds of tragedies that befall Americans. When it happens, the president is called upon to act as a surrogate for us, doing what we would do if we were there, saying the inspiring words we wish we had the eloquence to speak, imparting caring, commitment, and resolve. We also put ourselves in the position of the person being comforted, as he makes us feel cared for and protected even at a tragic moment. If he does it right, he can create some measure of national unity, if only briefly.

We've always assumed that by the time a politician gets to be president, he's already good at this sort of thing, because he would have had to enact versions of it a thousand times. Every time a voter comes up and says, "Sir, I've got diabetes and I want you to protect my Medicare," he has to create that human connection quickly while the cameras click away, to show her that he cares about her and he'll come through for her. Sometimes those interactions have a long life; George W. Bush gave a hug to a girl whose mother died on September 11, and his political allies turned it into an ad that blanketed the airwaves leading up to the 2004 election ("He's the most powerful man in the world and all he wants to do is make sure I'm safe, that I'm okay," the girl says in the ad). Bill Clinton was mocked for saying "I feel your pain," but that was one of the core themes of his 1992 campaign, that he understood what people were going through in a tough economic time, while his opponent was removed and oblivious. Whether you loved him or hated him, there was no question that Clinton's ability to connect with people was one of his greatest strengths.

A president might communicate his empathy in a carefully written speech, but more often it comes through in those unscripted moments, when we get to watch him making that connection with an ordinary person. Most of us realize that to a degree it's artificial, that both the president and the person he's comforting are aware that the interaction is being photographed. But we hope that it can still be an expression of something real.

But Donald Trump can't do it, and it isn't just because he doesn't have as much practice on the campaign trail. It's because of who he is.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We knew what we were in for when he announced that he'd travel to Puerto Rico Tuesday, a brief visit that came after he spent days insulting the mayor of San Juan over Twitter and complaining that Puerto Ricans were a bunch of lazy bums unwilling to do enough to help themselves recover from the storm (they "want everything to be done for them when it should be a community effort," he said). The problem was obvious: The mayor and the people she represents weren't fulsome enough in their praise of the president, and since at the core of his character is a division of humanity into people who admire and praise Donald Trump and people who don't, that made them the enemy. Just as he spent months talking about how unprecedented his election victory was, every time Trump talked about Puerto Rico he'd insist that the aid effort was going great and everyone was giving his administration high marks.

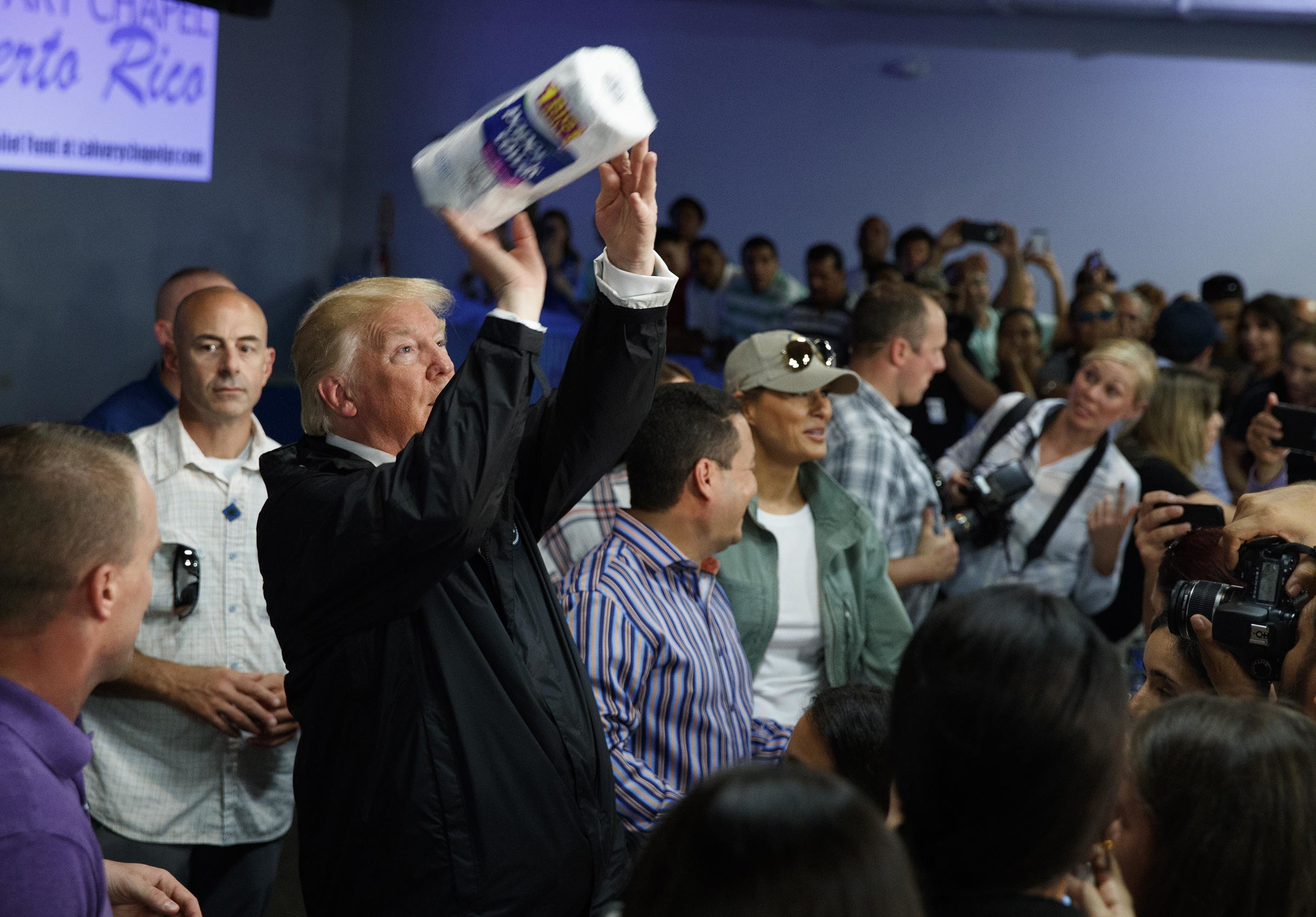

In other words, it was all about him and how terrific he is. And when he showed up in Puerto Rico, he said one gobsmacking thing after another. He told them that they should be very "very proud" of the relatively low death count there, particularly when you compare it to "a real catastrophe like Katrina" — which is like saying to someone, "Hey, too bad your mom died, but I heard about a whole family that got killed in a car crash, so you should be happy!" He chided them for costing too much money to help: "I hate to tell you, Puerto Rico, but you are throwing our budget out of whack." He praised the island's governor for "appreciating what we did," and asked their congressional representative to repeat the praise she had given him earlier ("say a little something about what you said about us today").

For whatever combination of reasons — a demanding father, a lifetime spent as a bombastic salesman — Trump feels an unquenchable need to characterize anything that might reflect on him, no matter how remotely, as a smashing success, and that takes precedent over any other consideration. He even said about the massacre in Las Vegas, "What happened is, in many ways, a miracle," continuing that "how quickly the police department was able to get in was really very much of a miracle. They've done an amazing job."

That's what he said after 59 people were murdered and hundreds more injured. If your reaction to that is, "Is he some kind of lunatic?" you're not alone. Any normal human being would understand that after such monumental carnage, you can and should praise the efforts of the first responders, but if you do it in a way that sounds like you're trying to find the upside to the river of blood pouring through the streets of a major American city, you aren't just not doing what a president is supposed to. You're not doing what a human being is supposed to.

But that's who Donald Trump is. And it won't be the last time he reminds us.

Paul Waldman is a senior writer with The American Prospect magazine and a blogger for The Washington Post. His writing has appeared in dozens of newspapers, magazines, and web sites, and he is the author or co-author of four books on media and politics.