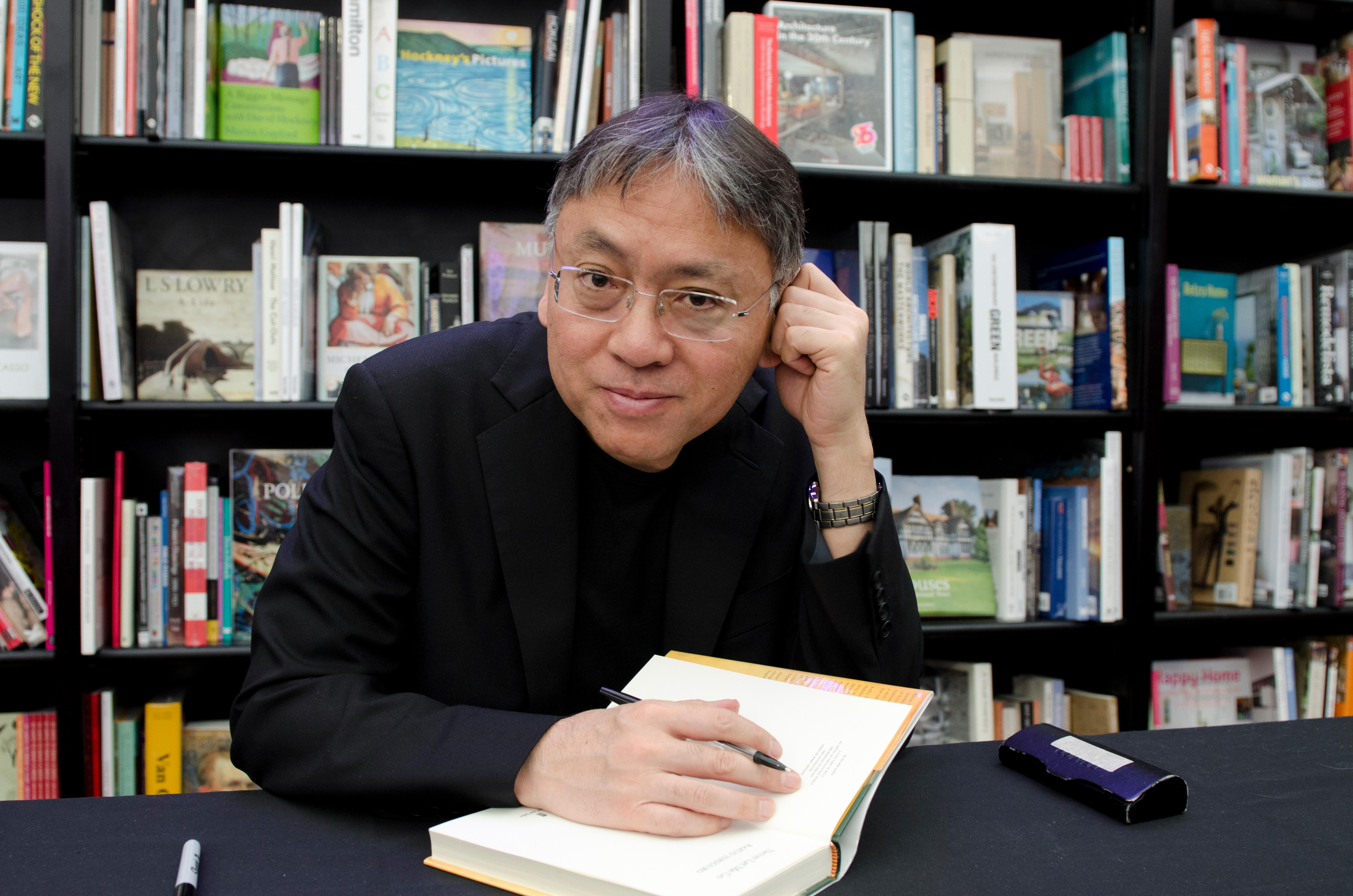

The underestimated Kazuo Ishiguro

Why his self-effacing novels merit a Nobel Prize

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's safe to say Kazuo Ishiguro was, if not quite a Bob Dylan–level dark horse, not really on anyone's radar to win the Nobel Prize in Literature. Neither the Rumpus nor the New Republic put Ishiguro in their lists of Nobel hopefuls, for instance. And though Ishiguro is an artist who has — and has earned — an enormous amount of readerly goodwill, his last two books, Nocturnes and The Buried Giant, received mixed reviews. Most of his popular fame rests on two books: The Remains of the Day, narrated by a butler whose beloved former employer turns out to have been a Nazi sympathizer, and Never Let Me Go, a story about boarding school children who turn out to be clones grown and raised for eventual organ harvesting. Perhaps not coincidentally, both have been adapted into movies.

It would be a little absurd to use the occasion of a Nobel Prize to claim the winner gets no respect. On the other hand, Ishiguro's work is often deliberately self-effacing. He rarely goes in for stylistic flourishes, and the mood of his work is usually (though not always) quiet, even mundane. So while Ishiguro is not precisely underrated, let's call him underestimated. Even in his more self-consciously ambitious work, he's not really drawing attention to himself.

So what is it about his work that merits this kind of prestige? That "in novels of great emotional force, [he] has uncovered the abyss beneath our illusory sense of connection with the world" is the official explanation. As explanations go, it's a little mysterious.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Though The Buried Giant deserved the mixed reviews (I gave it one myself), its chosen conceit contains the answer to this question. The book is about a mythical England which is under a fog of forgetting. Lifting the fog, it eventually becomes clear, will mean remembering terrible things. Some of those terrible things were done by the very characters we are following through the book, who, advanced in years and under the spell of the fog, have little idea what they have done. What also becomes clear is that remembering the past will cause, in turn, terrible bloodshed.

You would expect this kind of story to progress a few different ways. One is to pen a story on the virtues of forgetting — of moving on, letting the past stay buried. Another is to praise remembering: justice and hard truths at all costs. Or you could try to thread the needle such that you try to write a story about forgiveness that is not ultimately about forgetting. Instead, Ishiguro chooses not to choose. The guilt of his characters is a simple fact, one that will be made right neither by forgiveness nor by bloodshed, one that ultimately cannot be solved by forgetting.

Only a few of Ishiguro's characters are what you might call "bad people" — malicious, predatory, or cruel. They do exist: Christopher, the protagonist of When We Were Orphans, eventually discovers that his life was financed by his mother's rape at the hands of a warlord named Wang Ku. Wang Ku is certainly a villain; but the book focuses more on Christopher himself, who asks his mother, at the end of the book, for forgiveness.

Forgiveness for what? It's a good question. ("Did you say forgive [him]? Whatever for?" asks his mother, who cannot recognize him.) Christopher hasn't done anything wrong, exactly; he didn't know he was profiting from evil. The entire book tracks his journey to uncover the mystery of his past. At the same time, he's guilty. So is Stevens, the butler who narrates The Remains of the Day, for the work he does for the fascist he adores. So is Masuji Ono of An Artist of the Floating World, who created propaganda for Japan in World War II (among other failures).

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Novels about ordinary people who profit from evil — because they themselves are unimportant, because the ask isn't high, because they've willfully forgotten or been shielded from the truth — what could capture more clearly the situation of most of Ishiguro's readers? Certainly they can find themselves entangled in this situation wherever they turn. You don't need to look for anything big. To pick one example: If you are reading this story on an iPhone, it's easy enough to find a story about the conditions under which your phone was produced.

So if you want to know why you ought to read Ishiguro — and why he deserves to be highlighted, to you, at this particular moment — one answer is that he is the novelist of guilt. The guilt is unavoidable; it's something you acquire by being alive. It's not dischargeable; you'll always have done what you did. And yet because of its very universality, it's something you cannot shrug off. It's not enough to say that everybody fails, takes short cuts, or does wrong things. It won't free you to say you're not the only guilty party.

And what will? Probably nothing. Ishiguro's books aren't solutions or how-to guides. His depiction of rituals of forgiveness and penance in The Buried Giant are deeply skeptical. What matters is that you are guilty. However you choose to acknowledge or avoid it, that's the truth. And it always has been.

B.D. McClay is a senior editor at the Hedgehog Review.

-

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'

5 cinematic cartoons about Bezos betting big on 'Melania'Cartoons Artists take on a girlboss, a fetching newspaper, and more

-

The fall of the generals: China’s military purge

The fall of the generals: China’s military purgeIn the Spotlight Xi Jinping’s extraordinary removal of senior general proves that no-one is safe from anti-corruption drive that has investigated millions

-

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’

Why the Gorton and Denton by-election is a ‘Frankenstein’s monster’Talking Point Reform and the Greens have the Labour seat in their sights, but the constituency’s complex demographics make messaging tricky

-

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'

Walter Isaacson's 'Elon Musk' can 'scarcely contain its subject'The latest biography on the elusive tech mogul is causing a stir among critics

-

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!

Welcome to the new TheWeek.com!The Explainer Please allow us to reintroduce ourselves

-

The Oscars finale was a heartless disaster

The Oscars finale was a heartless disasterThe Explainer A calculated attempt at emotional manipulation goes very wrong

-

Most awkward awards show ever?

Most awkward awards show ever?The Explainer The best, worst, and most shocking moments from a chaotic Golden Globes

-

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. deal

The possible silver lining to the Warner Bros. dealThe Explainer Could what's terrible for theaters be good for creators?

-

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'

Jeffrey Wright is the new 'narrator voice'The Explainer Move over, Sam Elliott and Morgan Freeman

-

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020

This week's literary events are the biggest award shows of 2020feature So long, Oscar. Hello, Booker.

-

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortality

What She Dies Tomorrow can teach us about our unshakable obsession with mortalityThe Explainer This film isn't about the pandemic. But it can help viewers confront their fears about death.