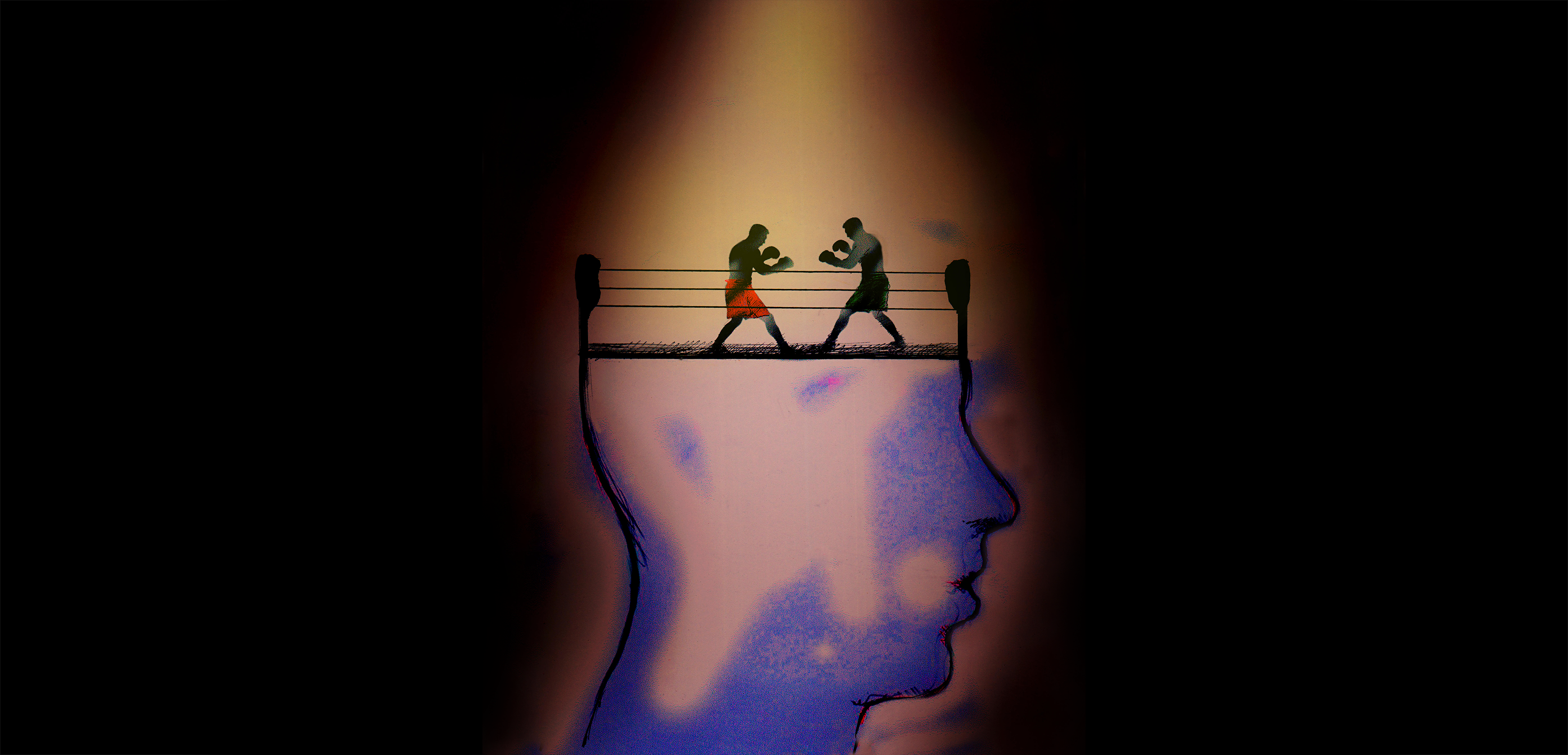

You weren't supposed to have to think about politics

Politics are here to be a servant to better pursuits. It's time we treat them that way.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

You were not supposed to have to think about politics.

Not this much, anyway. Good citizenship was not supposed to entail paying obsessive attention to a 24-hour news cycle. It was not supposed to demand conversational knowledge, at any given moment, of at least 15 issues of national importance. It was not supposed to be the task of each American to have An Informed Opinion on What the Government Should Do about every matter of state.

America's founders never wanted politics to be a major occupation of your mind. It was not supposed to feature prominently among your worries. Most of the time, it was not supposed to be your responsibility.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

I know, I know, we learn in grade school that America is a democracy, and each of us must do our part to ensure good governance "of the people, by the people, and for the people." This may be inspirational for children, but it is not entirely true.

The United States' government has democratic elements, yes, and, in some ways, it has become more democratic with time. (In other ways, it has become less democratic, and I'll leave it to the reader to decide whether the net change is a loss or gain.) To say our country is a republic rather than a democracy is also misleading, but it does remind us of an important point: Our federal system is representational. It is not direct democracy. Each of us does not weigh in on everything. Instead, we periodically vote on representatives who will weigh in on our behalf while we do other, better things.

This is with good reason. At the most practical level, direct democracy was always impossible for a country of the United States' size. And even now, assuming technology could be secure enough to use without concern over hacking and other malicious manipulation, there is cause to reject direct democracy: A system designed to force every responsible citizen to pay constant attention to politics is not desirable.

We elect representatives to do the great bulk of our politicking for us because we have more important things to do. We have families to raise and jobs to work and homes to maintain. We have our own areas of interest and expertise, our own relationships to cultivate. And, crucially, we have limited time, energy, and mental space. Some of us may choose to make politics our hobby or occupation, but all of us should not have to make that choice.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Politics is one aspect of our society. It is one part of many. We all no more need to be politicos, amateur or professional, than we all need to be philosophers or writers or tailors or dog rescuers or plumbers. Philosophy, books, clothes, rescue dogs, and working toilets are all important, just as politics is, but they are not everyone's concern all the time. They are some people's profession and the hobbies of others, but for most of us, these and any other field of work or pastime are only occasionally encountered.

You may object that politics is unique, that it is not comparable to writing or plumbing, that the division of its labor must be universal in a system of universal suffrage. Perhaps, with former Rep. Barney Frank (D-Mass.), you believe "government is simply the name we give to the things we choose to do together." If that is true, we must all choose to do politics, and to do it often.

But I submit that Frank's line is at once an understatement and an overstatement. It is an understatement in that politics — or, more properly, the state — is not what we choose to do together. It is what we are forced to do together. I say "forced" not as a negative judgment (that is another question for another time), but as a description of the reality that the state is considered to hold the monopoly on legitimate violence in our society, and that it uses this monopoly to compel a degree of our participation.

But Frank's definition is an overstatement, too, in that politics is not the totality of what we do together, and labeling it thus erases civil society. To ignore all the non-government, non-business things we choose — actually choose — to do together is dangerous. It is also understandable, for politics is eating an ever-larger portion of our lives. Whether we want to choose to do politics with any regularity feels increasingly irrelevant; it is always there, whether we like it or not. The preeminence Frank assigns the political, the way he implicitly sweeps away our non-political yet still communal activities, accurately reflects politics' creeping infestation of obligation in our lives.

Some of this is specific to our present climate. As Ezra Klein documented in a perceptive piece at Vox last month, President Trump governs by the principle that "attention … alone creates value." Trump's "rule, his realization, is that you want as much coverage as possible, full stop," Klein writes. "If it's positive coverage, great. If it's negative coverage, so be it. The point is that it's coverage — that you're the story, that you're squeezing out your competitors, that you're on people's minds." Trump is always on our minds, and he is teaching the rest of Washington his methods. (Incidentally, this is part of why I recommend reading the president and other politicians rather than watching them. It creates some mental distance.)

But politics was an invasive species in our mental habitat well before Trump came along. He is at least as much a beneficiary of this change as he is a creator of it. Like Frank's comment, he both reflects and advances the dysfunction. With or without Trump, the political steadily is replacing the civil, religious, local, and familial as a source of identity in the public sphere. How we think of ourselves and how we define what it means to be a good member of our community is increasingly framed in political terms.

"Our ancestors were more static, their pursuits more local," writes Gracy Olmstead, a contributor here at The Week, for the Intercollegiate Review. "While some did travel in search of a new life or better prospects, most remained in place. They were known and identified by family, neighbors, and friends. Their personal and political personality unfurled amid a built-in community." Religious participation, however casual or nominal, likewise "presented opportunities for camaraderie, philanthropic support, and love."

But today, Olmstead continues, the "ties of faith and place" and other such civil identifiers are supplanted by a "struggle … to match our displaced and atomized selves with some sort of tribe or community, and thereby create a specific identity." We feel obliged to think about politics all the time because it is constantly presented to us, but also because it is an ever more significant part of how we think about ourselves.

This ought not to be so. It is exhausting for things to be so. It is right, normal, and reasonable for most people not to think about politics most of the time. However flawed its function, that is one great virtue of the theory of representative government: It frees us alike from the tyranny of rule by others and the tyranny of having to think about politics every damn day.

This freedom is part of why the framers of our government eschewed direct democracy. In a letter to his wife, Abigail, in 1780, John Adams described his own exclusive focus on the "Art of Legislation and Administration and Negotiation" as a gift to posterity. He gave his life to politics so his children could be free of it, so they might study "Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture," and so their children might "study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine."

Politics is here a servant to better pursuits. It is not our highest obligation, the sum of "the things we choose to do together." It is a necessary but not especially noble substrate on which we build greater things.

Yes, politics matters. Of course politics matters. I spend much of my days writing about why and how it matters. But it does not matter most. It is not our most important commitment or identifier. It is not our greatest concern or responsibility. Or rather, it should not be.

Yet what is and what should be are rarely the same, and I am not optimistic that the political will cede the mental territory it has captured. The 24-hour news cycle will not die in the foreseeable future. Trump will leave Washington, but the incessant attention his tenure has demanded will not exit with him. The climate Klein's article describes will ebb and flow, but mostly flow. At the individual level, we cannot change this. We cannot ignore politics, even if we want to.

We can, however, change how we think about politics. We can refuse to let it claim more of our minds and our time. We can limit our political attention to select issues that trouble us most, rejecting the demand that we all have an opinion on every topic. We can instead choose to care for a few things well. Most of all, we can deliberately cultivate meaningful non-political relationships and commitments as a counterbalance to our political identities and obsessions.

This is a patchwork remedy, and perhaps an unsatisfying one. It will not end the exhaustion of modern politics. But it may temper and contain it, and prevent its infestation of the good parts of life.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the deep of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred