The limits of Messi's magic

Lionel Messi can't save Argentina in this World Cup. But it's not his fault alone.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Just before Croatia embarrassed Argentina in what was each country's second 2018 World Cup game, TV cameras captured perhaps the most telling moment of the entire tournament: During his home country's national anthem, Argentina's captain/superstar/savior Lionel Messi had his head in his hands, looking defeated before the ball was even kicked.

This is the image that best captures the mess that has been Argentina's World Cup campaign. Despite nabbing a last-minute 2-1 win against Nigeria in their last group stage game Tuesday and narrowly sneaking themselves into the Round of 16, Argentina isn't convincing anyone they're a real trophy contender. Their 3-0 demolition at the hands of Croatia last Thursday still looms large — not to mention their stunning 1-1 draw against Iceland to open the tournament.

Prior to Tuesday's decisive showdown with the Super Eagles, the blame for Argentina's woes had fallen squarely on Messi. The forward was expected to carry the worst Argentina team of his career to glory this year and finally claim the international title that has long eluded him. Though the quest continues, it now pits Argentina against powerhouse France in the knockout round — and no one would be surprised if the Albiceleste goes down, finally ending the disaster that has been this World Cup for the team.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

With Messi freshly turned 31 years old, it's likely that if and when Argentina sputters out of Russia, that's curtains for No. 10 in the World Cup. One question will remain: Should Messi be held singularly accountable for his team's failures?

Unless he somehow drags this team to the ultimate title in world soccer, the answer will be a resounding yes. He's the captain, he's the best player on the team, he's the superstar. When the team wins, he is praised — and when they lose, especially over and over again on the global stage, he should be scorned.

But despite what you may read zipping around the internet, the reality is that this blame is misplaced. Messi deserves some scrutiny, yes — but certainly not the most, and nowhere near the amount he will receive from aggrieved fans.

For starters, this Argentina team is terrible. On the field, it's only narrowly worse than the 2014 squad that Messi carried until the end. But the problems start at the federation level, where the Argentine Football Association (AFA) rules over a tragic kingdom. Corruption led to the resignation of a president, four coaches in four years, and such mishandling of budgets that Messi himself had to pay for security guards for the national team.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The biggest mistake the AFA made, however, was assigning Jorge Sampaoli to the manager spot last year. Anyone who'd caught even a minute of Sampaoli's tenure with Chile, or his stint with Sevilla after that, could have told you two things. One: Sampaoli is a great and innovative coach. Two: His preferred style is horribly mismatched to this Argentina team.

Sampaoli's system relies on chaos and running. Messi — and so, by extension, Argentina — relies on precision and a system wherein he has the freedom to create moments of magic. Either the AFA didn't understand its roster, or it felt that Sampaoli's hot personality could overcome this divide. Either way, to say the federation failed is to undersell the crisis of the Albiceleste.

In the lead-up to Tuesday's game against Nigeria, reports emerged suggesting that over the weekend, the players staged a Messi-led revolution that tried to get Sampaoli ousted. When the AFA refused, the team reportedly decided that they would choose their own lineup for Tuesday's game anyway, forsaking Sampaoli's direction.

The rumors turned out to be not quite true. Per Mundo Albiceleste, there was indeed a team meeting Friday evening between all the players — but also present were AFA president Claudio Tapia, Sampaoli, and the rest of the coaching staff. By all accounts, the conclusion reached at the meeting was that Argentina would only advance if they did so together.

Still, that the global media and soccer fans alike believed the whispers of a dramatic, mid-Cup coup speaks to the general sentiment around this Argentina side. Everyone seemed to agree that the players coaching themselves could not be any worse than the squad's performance under Sampaoli.

And even as he "led" his team to a win against Nigeria, it's fair to say Sampaoli still got it wrong. His refusal to play Giovani Lo Celso — Argentina's most complete center midfielder — or Paulo Dybala almost cost the Albiceleste, as did his insistence on playing Gonzalo Higuaín for the full 90 minutes. If Argentina had been eliminated, it's unclear how Higuaín could've stomached his return home, given his late-game whiff that echoed so many failures past.

Sampaoli simply isn't built to adapt — and it was very nearly his side's downfall. Maybe he's incapable of another system, or maybe he's foolish enough to believe that Croatia would be stumped by a half-hearted press or Nigeria by Enzo Perez hobbling around the pitch. Either way, his players did not buy in completely, and they pulled out the win against Nigeria only because of individual moments of greatness from Messi and teammate Marcos Rojo.

But the limits of Messi's magic were clear even before he and his team were backed against the wall. In Argentina's first match against Iceland, Messi was constantly triple-teamed, pushed, and shoved off his rhythm; he ended the game scoreless after infamously failing to convert on a penalty kick that would've given his team the win. Playing physical with Messi is a tactic opponents will continue to employ for the rest of the tournament — and unless Argentina drastically changes its strategy, it's likely to work.

Still, Messi can carry his team. He got Argentina going in the must-win match against Nigeria with a magisterial goal in the 14th minute, and his teammates still look to him to relieve pressure and get them into scoring positions. The real problem is that for Argentina to succeed at the level its fans have come to expect, Messi must be all things to all people. He needs to make his teammates better in ways that few other players are expected to, but he also needs to step up individually in the highest-pressure moments and score the goals that remind Argentine fans of the legendary Maradona.

Messi is more artful and tricky at heart; he does things from distances and angles that shouldn't be possible, but he's less a domineering, otherworldly force. His main role is to be bigger than the game, and to make his teammates believe that they can win every game because they have the world's best weapon on their side. That is why so many believed that an Argentina team that barely made the World Cup in the first place could actually compete for the trophy. (I believed it too, right on this very website.)

But whether by Sampaoli's hand, or by a lack of talent, or by Messi's failure to be the alpha and the omega, Argentina probably won't win this tournament, and Messi's streak of falling short at the World Cup will always be mentioned in conversations about his legacy. For some, Messi can never truly be the greatest of all if he doesn't win a World Cup with Argentina, like Maradona did. He's won the Champions League; he's won countless La Liga titles; he is, by all statistical or even anecdotal evidence, the greatest singular force to ever step on a soccer field. But if he doesn't do the impossible and lift the World Cup trophy this summer, it won't matter — even if the failure was hardly his fault alone.

The narrative awaits, and it will be written in permanent ink: Here lies Lionel Messi, a pretty good player who never won anything important for Argentina.

What a shame.

Luis Paez-Pumar is a freelance writer based out of New York City, specializing in sports and culture commentary. A graduate of New York University, Luis lives in Brooklyn with a small pug named Clyde. In his free time, he spends his time watching too much television and trying to read books faster than he can buy them.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.

The hottest Super Bowl ad trend? Not running an ad.The Explainer The big game will showcase a variety of savvy — or cynical? — pandemic PR strategies

-

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.

Tom Brady bet on himself. So did Bill Belichick.The Explainer How to make sense of the Boston massacre

-

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIII

The 13 most exciting moments of Super Bowl LIIIThe Explainer Most boring Super Bowl ... ever?

-

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio State

The enduring appeal of Michigan vs. Ohio StateThe Explainer I and millions of other people in these two cold post-industrial states would not miss The Game for anything this side of heaven

-

When sports teams fleece taxpayers

When sports teams fleece taxpayersThe Explainer Do taxpayers benefit from spending billions to subsidize sports stadiums? The data suggests otherwise.

-

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseball

The 2018 World Series is bad for baseballThe Explainer Boston and L.A.? This stinks.

-

This World Series is all about the managers

This World Series is all about the managersThe Explainer Baseball's top minds face off

-

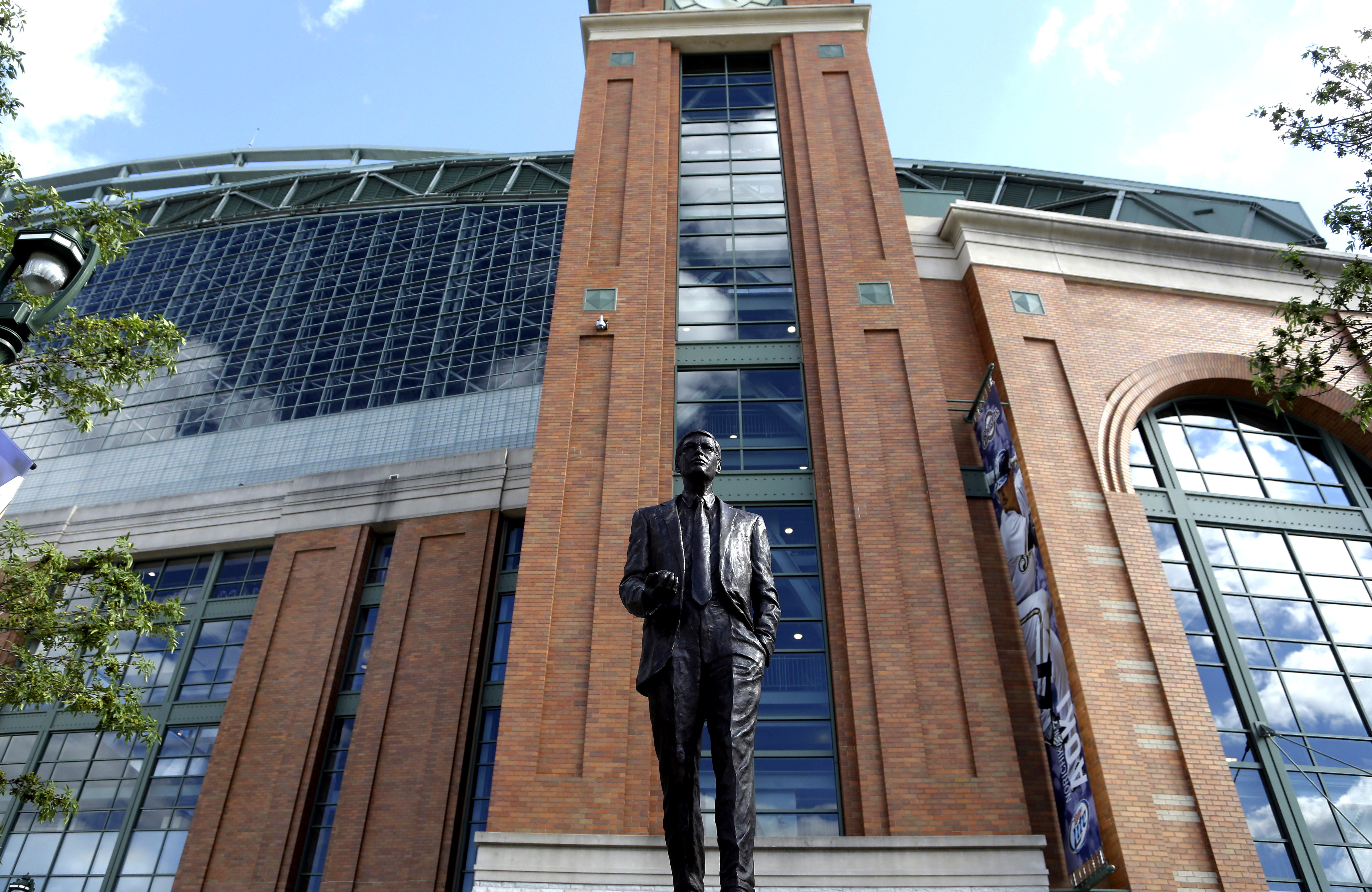

Behold, the Bud Selig experience

Behold, the Bud Selig experienceThe Explainer I visited "The Selig Experience" and all I got was this stupid 3D Bud Selig hologram