The evolution of the Supreme Court

The nation's highest court dominates our politics. But it didn't start out so powerful.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The nation's highest court dominates our politics. But it didn't start out so powerful. Here's everything you need to know:

How did the Founders view the court?

While the Constitutional Convention of 1787 agonized over the specific powers delegated to the legislative and executive branches, the Framers devoted relatively little energy to the judiciary, leaving its powers mostly vague and undefined. Alexander Hamilton argued that the judiciary would be the "least dangerous'' branch, with the justices dependent on Congress for their salaries and budget. Without the "purse" or the "sword," Hamilton maintained, the court's rulings would depend "neither on force nor will, but merely judgment," with the court's power resting in its prestige. During the first years of its existence, the Supreme Court heard only four cases. When John Jay, the first chief justice, resigned in 1795 to become governor of New York, newspapers framed the move as a promotion. The court, Jay complained, lacked "energy, weight, and dignity."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When did that change?

With John Marshall, the nation's fourth chief justice. Appointed in 1801, the 45-year-old Virginian almost immediately began carving out a more prominent role for the Supreme Court. In the landmark case Marbury v. Madison (1803), Marshall asserted the court's power to strike down laws passed by Congress as unconstitutional. "It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is," Marshall wrote, establishing judicial review as a keystone of American constitutional law. The Marshall court also shaped much of the federal system that we know today, repeatedly ruling that federal laws are superior to state laws. This enraged small government–minded politicians, such as then–President Thomas Jefferson, who accused the Marshall court of judicial overreach. "The constitution," Jefferson wrote, "is a mere thing of wax in the hands of the judiciary, which they may twist and shape into any form they please."

Who succeeded Marshall?

After 34 years as chief justice, Marshall gave way to Roger B. Taney, who came from a family of slaveholding Maryland tobacco planters. In one of the most infamous decisions in Supreme Court history, Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), the court ruled against Dred Scott, an enslaved man from Missouri who sued for his freedom. Blacks, Taney wrote, could not be citizens and "had no rights which the white man was bound to respect." The court further ruled that the federal government could not restrict slavery in the territories, striking down the Missouri Compromise of 1820.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What was the impact of Dred Scott?

It was a disaster. Taney had hoped to end the bitter national debate over slavery by making it settled law. Instead, the court's decision further polarized the country, emboldening Southern slaveholders while hardening opposition to slavery — and tarnishing the court's reputation — in the North. When Taney ruled against President Abraham Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus for suspected Confederate partisans during the Civil War, Lincoln ignored the order. Taney feared that the White House might even try to arrest him as well, with Northern newspapers accusing him of treason. In 1863, congressional Republicans added a 10th justice to the bench to ensure more pro-Union rulings.

When did the court settle on nine justices?

After fluctuating between six and 10 justices, Congress in 1869 set the number at nine, and it has remained there since. But tension over the court's makeup continued. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, conservative courts struck down progressive legislation on child labor, minimum wages, and shorter workweeks. The conflict came to a head in the 1930s, when the court stymied much of President Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal legislation. Roosevelt pushed Congress to add as many as six new justices to create a liberal majority, railing against the Supreme Court as "nine old men." Roosevelt's "court-packing scheme" met with bipartisan backlash and was ultimately shelved after swing vote Justice Owen Roberts started to vote with the court's liberal bloc. Roberts' sudden shift — apparently a strategic attempt to save the court's integrity — has been dubbed "the switch in time that saved nine."

What about confirmation hearings?

For years, hearings were held only for controversial nominees, with most nominees confirmed on a voice vote. The first public hearings were held in 1916 for President Woodrow Wilson's nominee Louis Brandeis, the first Jewish Supreme Court justice. Confirmation hearings became a regular part of the nomination process only after the court ruled school segregation unconstitutional in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), increasing public interest in the court's impact on daily life. Brown was a 9-0 ruling, but in recent decades, the court has become increasingly polarized — especially in major, culturally controversial cases. Before 1940, fewer than 2 percent of the court's decisions were decided by one vote. Since then, it's been about 16 percent. The current court has decided 21.5 percent of its cases by a 5-to-4 ruling. Chief Justice John Roberts himself has said that if the court is perceived as clearly divided along partisan lines, "it's going to lose its credibility and legitimacy as an institution."

The (mostly) men in black

Since its creation, the Supreme Court has had 113 justices, and all but six have been white men. Today's court is the most diverse in history, with three women and two people of color. But in other ways it's incredibly uniform. While just over half of all former justices went to an Ivy League school, all of today's current justices have a degree from either Harvard or Yale. With the exception of Justice Elena Kagan, all of the current justices served on federal appeals courts. Kagan was the dean of Harvard Law School before becoming solicitor general. In the past, 58 justices were elected officials — including William Howard Taft, who became chief justice a decade after serving as president — but none of today's justices has held elected office and answered to voters. "I, for one, do think there is a disadvantage from having (five) Catholics, three Jews, everyone from an Ivy League school," said Justice Sonia Sotomayor in 2016, arguing that judges should be from more varied backgrounds. "We understand things from experience."

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’Feature Activists say a Supreme Court ruling has given federal agents a green light to racially profile Latinos

-

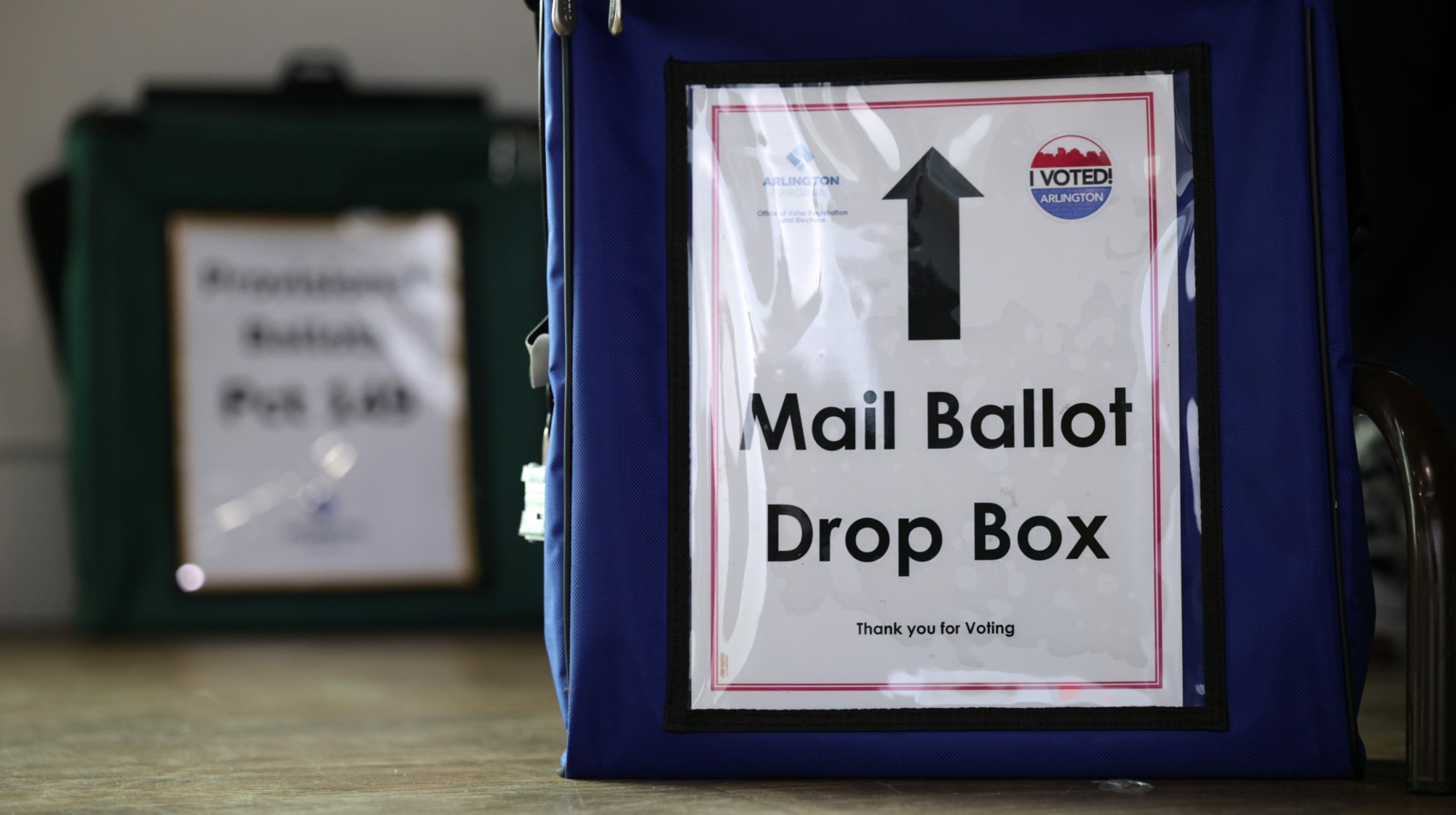

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limits

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limitsSpeed Read The court will determine whether states can count mail-in ballots received after Election Day

-

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme Court

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme CourtSpeed Read Even some of the Court’s conservative justices appeared skeptical

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party