How the new 2020 primary schedule gives Beto and Kamala a critical boost

It's called home-field advantage, and it's about to become a very big deal

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

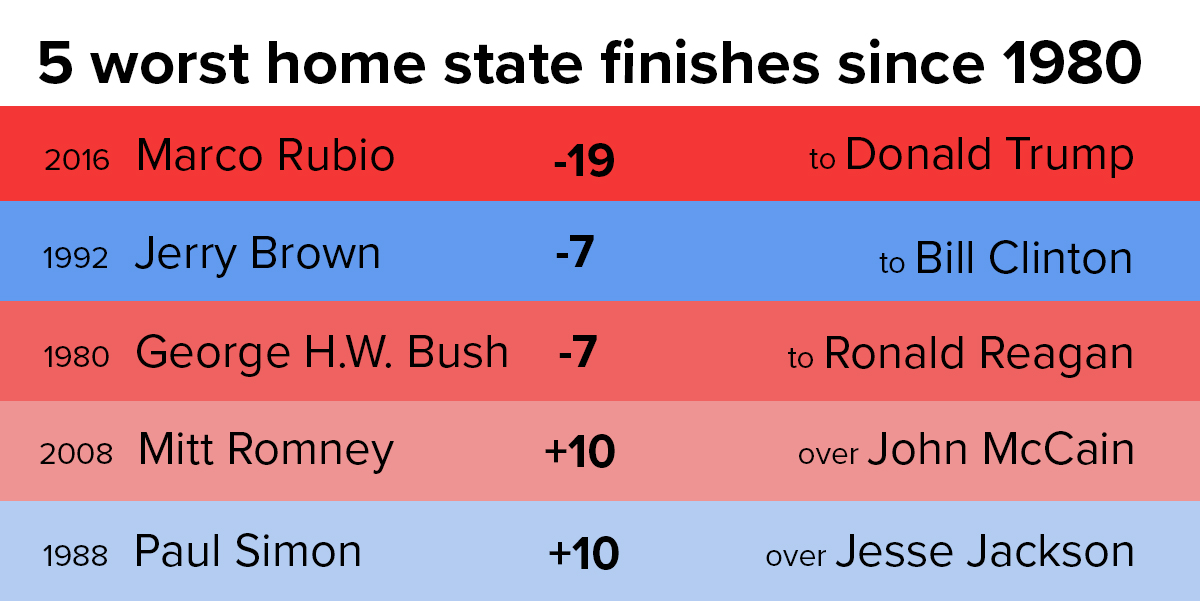

When Marco Rubio was humiliated in the 2016 Florida Republican presidential primary by eventual nominee and ongoing international scourge Donald Trump, he was the first serious GOP candidate to lose a home-state primary since George H.W. Bush lost Texas to Ronald Reagan in 1980. The longstanding home turf primary advantage held by presidential candidates is one of the main reasons that the new 2020 schedule — with California and Texas now voting on the enormous March 3rd Super Tuesday — may give a decisive early advantage to two Democratic hopefuls: Sen. Kamala Harris (Calif.) and former Rep. Beto O'Rourke (Texas). And because of Democratic primary rules, it might be hard for anyone else in the field to catch them.

How strong is the home state advantage? In 1988, five candidates made it to the Iowa caucuses in the Democratic primary, but by mid-March the race was effectively a three person scrum between Tennessee Sen. Al Gore, Massachusetts Gov. Michael Dukakis, and South Carolina civil rights activist Jesse Jackson. Yet despite winning no more than 4 percent of the vote in any of the Super Tuesday contests, Illinois Sen. Paul Simon still won his state's March 15th primary, beating Dukakis, the eventual nominee, by 10 points. In 2016, despite being hopelessly buried in the GOP delegate count, Ohio Gov. John Kasich won his Ohio turf, beating Trump by 11 points. And in 2004, both North Carolina Sen. John Edwards and former Vermont Gov. Howard Dean won their states' contests long after they had publicly withdrawn from the race. In other words, home field advantage plays, even well past the point where voters know the ultimate outcome.

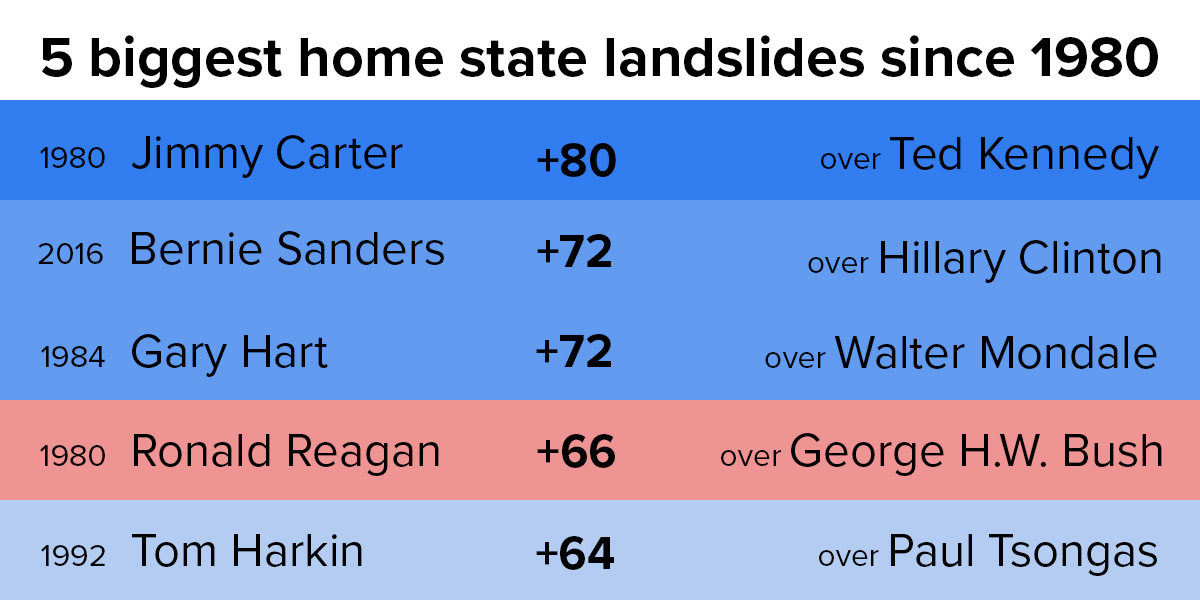

The home state advantage in both party primaries is robust and longstanding. I compiled data going back to 1976, and found that, on average, home state candidates won 37 of 40 contested primaries and caucuses by an average of 37 points. These calculations exclude races where the home state candidate had withdrawn from the race (like Dean in '04) or where the home state candidate no longer faced an actively campaigning challenger in the race (like Democrat Al Gore in 2000 over the long-withdrawn Bill Bradley in Tennessee, or Republican Bob Dole in the 1996 Kansas caucuses). But they do include races that were functionally uncontested, as with Sen. Tom Harkin's 1992 Iowa blowout, where the other candidates ceded the state to him. If you exclude 1976, which featured a peculiar number of home state landslides, the average native turf boost is just under 35 percentage points. The effect appears to be diminishing somewhat over time, as the post-2000 advantage averages 27 points.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

At the root of the phenomenon is name recognition and familiarity (unless you're Rubio). Most presidential candidates who are not already national figures struggle for name recognition even in their own states. Forty percent of Michiganders, for instance, have no opinion of low-profile Sen. Gary Peters (D). In a crowded field, being known and not despised on your own territory can be a pretty significant advantage (again, unless you're Rubio). And state voters tend to like their representatives and governors more than the rest of the country does. That's how, despite being widely reviled outside of Texas, Ted Cruz was able to cling to power last year against O'Rourke on the strength of his stronger local appeal.

How might the home field advantage affect the chase for the 2020 Democratic nomination? Like with the Republicans in 2016, there may be more than a dozen serious candidates at the outset. Just last week alone, Congresswoman Tulsi Gabbard (Hawaii) and former HUD Secretary Julian Castro announced their intentions to pursue the nomination. But in contrast to what Trump was able to do to the Republican field, no Democrat is going to be able to pull decisively away by winning 30 or 35 percent of the vote in state after state. That's because the Democrats use exclusively proportional rules for awarding delegates, meaning candidates get roughly the same percent of available pledged delegates as their percentage of the overall vote. Trump parlayed a series of plurality wins against a crowded field into a towering delegate advantage because of how many Republican primaries are winner-take-all or winner-take-most. Had Republicans used Democratic rules, Trump would likely have arrived in Cleveland for the Republican National Convention without a delegate majority, making possible the kind of scheming to keep the nomination away from him for which some party leaders yearned.

Imagine for a moment that six serious Democratic candidates survive the debate cattle calls, the scramble for money, resources, and staff, and the year-long slog from announcement to the Iowa caucuses. Start with the five candidates who have placed highly in lefty straw polls: former Vice President Joe Biden, Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders, Massachusetts Sen. Elizabeth Warren, Harris, and O'Rourke. Then add someone who is largely off the radar right now, like Oregon Sen. Jeff Merkley. For the first four contests, let's say for the sake of argument that Sanders wins Iowa and Nevada, Warren wins New Hampshire, and Harris wins South Carolina. Merkley fails to place in the top three anywhere and calls it quits, while Biden's steady if underwhelming double digits all over the map convince him to hang in for Super Tuesday.

And that's where California and Texas might prove crucial for Harris and O'Rourke. Moving them up and having the contest's two biggest delegate hauls on the same day, early in the calendar, will allow Harris and O'Rourke to bag a potentially insurmountable number of delegates. While neither the schedule nor the delegate totals for each state are totally finalized, we can get a pretty good idea of where things would stand. Let's give her home state of California to Harris by the post-2000 average of 27 points, as well as North Carolina, Georgia, and Alabama, all states where African-American voters will be critical. Give Massachusetts to Warren, Virginia, American Samoa, and the Democrats Abroad to Biden, Texas (by 27) and Tennessee to O'Rourke, and then Vermont and Oklahoma to Sanders. You can play around with the margins for the candidates in each state, but this would likely leave Harris with 400-450 delegates and O'Rourke with 250-300, followed by Warren and Sanders each with between 200 and 250 and Biden around 200.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In other words, Harris would lead O'Rourke by 100 or so delegates, and everyone else by as many as 200. And these are conservative calculations, assuming that in a crowded field like this, only Sanders blows everyone out in his home state, and that Harris and O'Rourke are kept under 50 percent in California and Texas, respectively. At that point, journalists might be inclined to treat this like a two-person race. As Sanders discovered in 2016, even a seemingly small edge like the 191 pledged delegate lead that Hillary Clinton had on him after Super Tuesday is hard to overcome with the party's proportional rules. It requires a sustained collapse in support for the leading candidate that is unlikely absent a massive scandal or health-related withdrawal. O'Rourke could catch Harris, but Warren, Sanders, and Biden would be faced with an insurmountable deficit. Even if the splintered field means that no candidate gets a majority, there will be enormous pressure to award the nomination to the candidate with the most delegates.

This scenario raises all kinds of fun strategic questions for the various campaigns. Can Harris and O'Rourke afford to punt on the first two contests in Iowa and New Hampshire? Can Warren and Sanders gain traction in the race if they appeal to such similar constituencies? How can Biden distinguish himself from the more openly progressive Warren and Sanders while also not losing support to the younger, similarly center-left O'Rourke? Can a dark horse like Merkley or Ohio Sen. Sherrod Brown crash this party with strong showings in the debates and early states? Should the other candidates mount serious runs at Harris and O'Rourke in California and Texas, even if just to keep their margins down?

For now, this is all just speculation. We're still more than a year out from Iowa, and anything can happen. Of this group, only Warren has announced officially — perhaps to box out Sanders and convince him to endorse rather than run against her — and there's no guarantee that either Harris or O'Rourke will run or be able to make it to the nominating contests, let alone win their all-important home turf. If you had told people in January 2015 that the host of Celebrity Apprentice would make it to Iowa and Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker would drop out before a single vote was cast, they would have laughed at you.

But Harris and O'Rourke's advisers are looking at the same primary calendar and delegate math that we are, and here's one thing I can guarantee you: They like what they see.

David Faris is a professor of political science at Roosevelt University and the author of "It's Time to Fight Dirty: How Democrats Can Build a Lasting Majority in American Politics." He's a frequent contributor to Newsweek and Slate, and his work has appeared in The Washington Post, The New Republic and The Nation, among others.