Fear the reparations backlash

The moral case for reparations may be strong. But the political and cultural costs would be extremely high.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

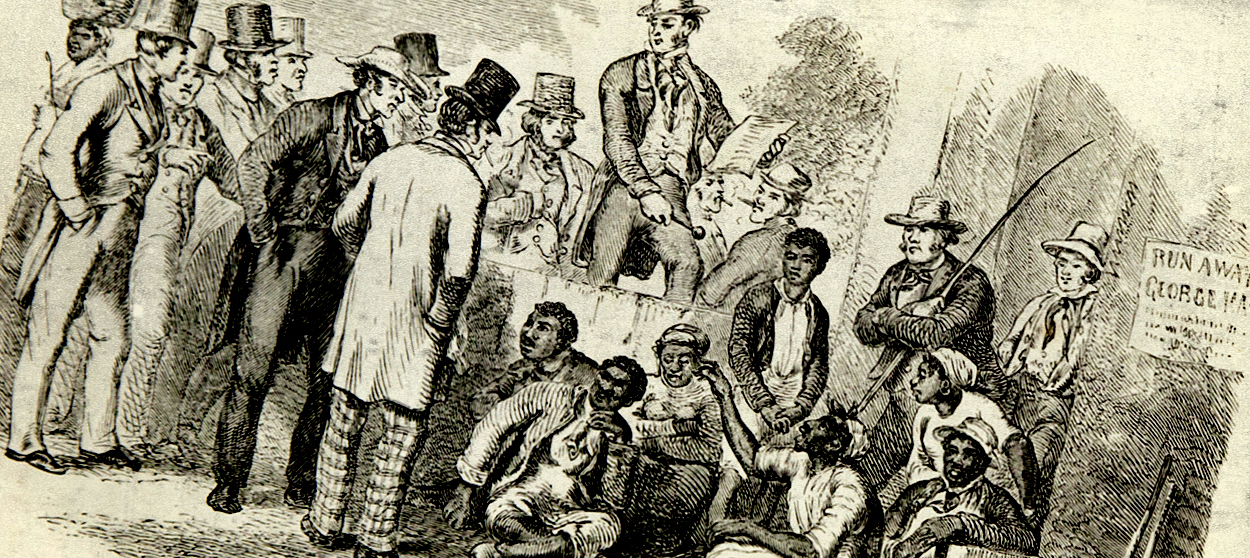

Democrats running for president in 2020 have already endorsed a long list of ambitious, controversial policies: The Green New Deal, Medicare-for-all, free college, the breakup of tech companies, and more. But one proposal belongs in a different category because it would seek to address the gravest injustice in American history. I'm talking about reparations for African-American descendants of slaves.

The idea of compensating Americans whose ancestors were brought to the New World by force and held in bondage for as long as 250 years has been debated numerous times in American history. The most recent case for reparations came in 2014 in the form of a powerful, deeply reported essay in The Atlantic by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Democratic presidential hopefuls aiming to stand out from the crowd have begun championing the cause. Sens. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.) and Kamala Harris (D-Calif.), and former Obama administration official Julian Castro, are already on board. The fact that David Brooks, a moderately conservative New York Times columnist who has taken recent swipes at both the Green New Deal and Medicare-for-all, has now endorsed the policy as well is a sign of just how mainstream it has become.

The moral case for reparations may be strong, but the political and cultural consequences of enacting the policy are likely to be extremely high. Far from serving as a moment of moral reckoning and healing for the country, as its advocates contend, it would inspire a severe backlash that would inflame tensions on both sides of the color line — and set the stage for future calls from other groups for acts of public restitution for past injustices. It's a recipe for greatly intensified civic anger and resentment.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

As I argued when he first published his essay, Coates' case for reparations was important and compelling — but also wrong-headed.

Coates asserted that American patriotism is a fraud. In his words, a form of American national pride that "proudly claim[s] the veteran and disown[s] the slaveholder," and that celebrates "freedom and democracy while forgetting America's origins in a slavery economy," is "patriotism à la carte." As he put it in one of the essay's most unforgettable lines, "To ignore the fact that one of the oldest republics in the world was erected on a foundation of white supremacy ... is to cover the sin of national plunder with the sin of national lying." In Coates' view — one endorsed by Brooks in his recent column — the only way for the United States to purify its patriotism and truly expiate its racial sins is for it to fully own, accept, and atone for them by enacting a policy of reparations.

That might sound good in theory, but it isn't at all the way it's likely to work in practice.

White Americans love to think well of themselves and the country — loving the United States not just because it is ours but even more so because they believe the country is good in itself, intrinsically worthy or deserving of love. Debating and attempting to enact a policy of reparations would force white Americans to confront their country's longstanding and persistent racism and place that reckoning at the core of how they view the country's history and themselves. That is quite likely to spark a defensive political, social, and cultural reaction.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Or perhaps I should say a further reaction. Coates wrote his essay, and I penned my response, with Barack Obama in the White House entering the final years of two terms as the first African-American president. Things look far bleaker two years into the presidency of Donald Trump. (I say that as someone who thinks it's too reductionistic to treat Trump's political rise as entirely a function of white racial resentment.)

Coates' original call for reparations was based on the hope that enacting the policy would make possible a final reconciliation or turning point in our history after which our racial sins could be left behind, with the country fully repaired and those sins at long last purged from our national soul. Brooks' account of what he hopes reparations could achieve is based on similarly lofty expectations.

But politics and history don't work like that. As Aristotle and Alexis de Tocqueville both point out in their own ways, an error made at the beginning of a new system of government — an error like the one committed by the American constitutional framers in founding a government on the principle of natural rights while also permitting the institution of slavery for members of a racial minority — can never be fully expunged. The mistake has been baked into the political system, along with its norms and traditions, from the start.

There are no political do-overs. No ways for a country to be born again. No national rites of purification.

What we're left with, instead, are a series of piecemeal efforts to redress injustices followed by reactions. The emancipation of the slaves and Reconstruction were followed by Jim Crow and the KKK. The Civil Rights Movement was accompanied and followed by the rise of the New Right. The presidency of Barack Obama was followed by Trump. The debate and passage of reparations legislation might prove healing for some, but it would almost certainly spark its own severe backlash among many others.

Might it nonetheless be worth the consequences? Perhaps — if we could know that demands for reparations would be limited to the descendants of slaves. But we can know no such thing. On the contrary, the dynamic of grievance politics in the United States tells us that reparations for African Americans would only be the start. Just as anti-discrimination law and affirmative action began with blacks and then spread to different races, ethnic groups, and other protected classes, so calls for reparations would quickly metastasize to different groups demanding recompense for past and present injustices.

If you doubt it, consider that just last week a resolution in the House of Representatives originally intended to single out those who traffic in anti-Semitism quickly morphed into a generic denunciation of "hate" directed against a laundry list of groups: "African Americans, Latinos, Native Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and other people of color, Jews, Muslims, Hindus, Sikhs, the LGBTQ community, immigrants, and others."

The case for treating the injustices suffered by African Americans in the United States as sui generis — and worthy of a uniquely aggressive response, including reparations — is quite strong. But that doesn't mean that activists who claim to speak for members of other groups will go happily along. They almost certainly will not. The one thing on which they are likely to agree is that the group that should be forced to pay repeated penalties for its collective sins is the white population of the country, and especially its supposedly most privileged class: straight, able-bodied white males.

Can anyone seriously believe that a politics organized around the effort of a series of minority groups to extract reparation payments from whites will be anything other than hideously toxic? The best way to avoid the brutal backlash that would follow may be to avoid provoking it in the first place.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.