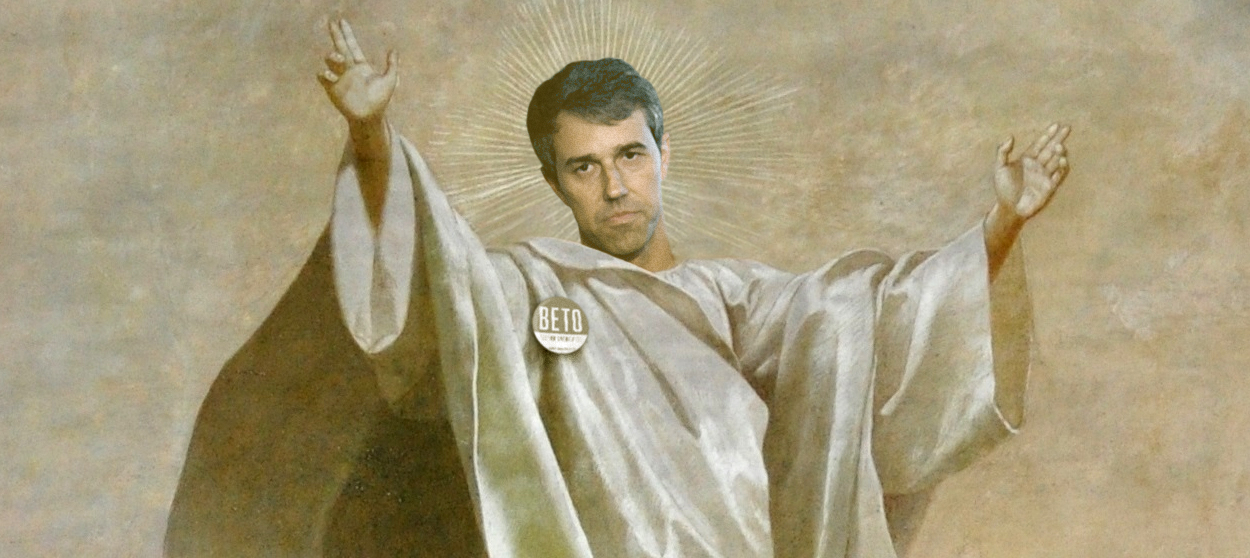

Don't idolize your 2020 pick

Beto is not your Christ. Neither is Trump, nor anyone else who runs for president.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Former Texas Rep. Beto O'Rourke officially launched his candidacy for the Democratic nomination by declaring to Vanity Fair he is "just born to be in it." And his supporters seem to have picked up on the "chosen one" undertones already, with a sign at a Saturday night rally in Austin glorying, "BETO IS OUR CHRIST."

This is, of course, just one sign. Maybe it was a joke. Maybe a single, still image misrepresents the grimace of devotion on the sign-holder's face. Maybe he's not there to support O'Rourke but to embarrass him — the Trump 2020 flag in the background shows counter-demonstrators were on hand.

But maybe not, and maybe the fact that a "BETO IS OUR CHRIST" sign is plausible as a sincere statement of political enthusiasm should give us serious pause as we plunge into the 2020 race. Ours is a culture friendly to idolizing public figures, politicians very much included, and this campaign season will offer plenty of opportunity for such misguided worship. Next year will be a high holy year of American civil religion, one marked by the (political) death of many gods. We place our faith in them at our peril.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

There is a sense, yes, in which this is nothing new: That sign-holding man in Austin did not invent political adoration. Former President Barack Obama's campaigns, for example, were known for their messianic themes, especially in 2008. Oprah Winfrey described him in the run-up to that year's primaries as a rare politician "who know[s] how to be the truth," which is difficult not to read as a reference to one of Jesus' most explicit claims of divinity.

But there are also at least three ways in which 2020 promises to take Americans' idolization of political leaders to fresh heights.

The first is structural. As the office of the presidency becomes ever more powerful and unbound by constitutional and social constraints, it is unsurprising to find Americans investing the role with salvific significance. When it seems the president can do anything he wants, it is natural to want him to do the anything you want. The modern Oval Office is the seat of unparalleled power, so it is foolish but not obviously irrational to believe that installing the right person is the solution to all our national woes. And absent dramatic reforms — which both parties extoll in the minority and abandon in the majority — the public conception of the president-as-savior, chosen to enact the hope of America, will continue to escalate alongside executive authority.

President Trump (and at least some of those jockeying to be his opposition) will further this dynamic by encouraging political idolatry from his fans. Trump's not the originator of our civil religion, but he has availed himself of it in unique ways. Think of how he demands intense personal loyalty; how he takes credit for the whole health of the economy ("the greatest jobs president God ever created"); how he dominates the news cycle and with it our mental real estate; how he declares himself the proper repository of our political faith ("I alone can fix it"); how he fixates on greatness.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

All of this pushes us, regardless of political affiliation, to think of the presidency as a near-omnipotent determinant of our national fate. When you're electing a god, the stakes are high!

The second factor at play in 2020 (and beyond) is the decline of other outlets for our religiosity. Now you may believe, as I do, that those without substantive faith commitments are inclined to bring religious fervor to their politics because we are made to find meaning in community life and transcendent ritual, and the emptiness we feel without them is a "pointer to something other and outer." Or you may simply think our brains evolved for religiosity.

Whatever the cause, the effect is the same: As religious participation declines, political participation appears as the only large-scale alternative. It can offer religion-like feelings of belonging, service, and commitment to truth — or at least a temporarily functional facsimile. So we substitute state for church, voting for prayer, celebrity endorsers for clergy, and human props for saints as we pick our preferred deity on the ballot.

And this is not a phenomenon exclusive to the explicitly religiously unaffiliated. As Timothy P. Carney argues in a compelling county-level statistical analysis of 2016 primary results at The American Conservative, "Many of Trump's earliest and most dedicated supporters were seeking a deeper fulfillment" than surface-level pledges of factory jobs and restricted immigration: "[W]hen Middle America turned away from church, they were missing something. And they sought it in Trump," while staying nominally Christian.

The third reason 2020 will see Americans particularly prone to political idolatry is how the race has been widely cast as a "good vs. evil" fight where we decide "what kind of country we are." This too is not new, though the rhetoric does feel more dramatic than in most elections of recent history. The other two factors are feeders here: Growth of executive power means the president has real capacity to do evil, and religiosity in political zeal pushes us to seek alliance with an ultimate good. We are awarding a very large prize, and we want our decision to be judged on the right side of history.

The trouble with all this is that the imperial presidency is a hazard to be dismantled, not grasped; that flawed and finite politicians are always doomed to insufficiency as recipients of our hope and trust; and that settling into a stark, "good vs. evil" mindset with our political opponents — the family members, friends, coworkers, and neighbors who vote differently than we do — makes it all but impossible to do anything but deepen that division, perhaps pushing them to reactively embrace the bad ideas we want them to abandon.

Beto is not your Christ. Neither is Trump, nor anyone else who runs for president. And that's true no matter how willing they may be to play that role or how good it may feel to let them play it. Political idolatry is a sure route to disappointment; your idol may look golden, but his feet are made of clay.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?

Why is the Trump administration talking about ‘Western civilization’?Talking Points Rubio says Europe, US bonded by religion and ancestry

-

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far right

Quentin Deranque: a student’s death energizes the French far rightIN THE SPOTLIGHT Reactions to the violent killing of an ultraconservative activist offer a glimpse at the culture wars roiling France ahead of next year’s elections.

-

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?

Secured vs. unsecured loans: how do they differ and which is better?the explainer They are distinguished by the level of risk and the inclusion of collateral

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred