Scandals no longer matter

The potency of scandal is waning in the political realm. The trend is unlikely to stop there.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If you're a movie mogul, media superstar, or journalist with a modicum of power, the lesson of the past two years is that a credible accusation of unprofessional or unethical behavior will cause a scandal that can instantly ruin your reputation and will quite likely destroy your career.

But if you're a prominent politician, the likely consequences are … far less obvious. And that tells us something important about the distinctive character of American politics at the present moment — and maybe about far more than that.

President Trump has said and done things that would have left the career of a journalist or media personality in tatters. Yet he won the presidency. The picture allegedly showing Gov. Ralph Northam (D-Va.) striking a flagrantly racist pose in a photo from his medical school yearbook would have led many businessmen to be canned. Yet two months after the scandal broke, Northam remains in office, and the public has largely moved on. Brett Kavanaugh was accused of high school behavior that in many other fields would have likely required at least a rote expression of contrition or regret. Yet he fought the charge rabidly, conceding nothing, and there he sits on the Supreme Court.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Then there's the exception that proves the rule: Al Franken, the former Democratic senator from Minnesota, resigned in December 2017 in the face of a handful of #MeToo accusations that some considered too mild to warrant such draconian consequences. Ever since, prominent Democrats have grumbled about how his rapid capitulation was a mistake. The clear implication for Joe Biden, whose nascent presidential campaign is currently enduring a slow drip of (so far) minor accusations of inappropriate touching on the part of the former vice president, is that he shouldn't react impetuously to the accusations, lest he end up following Franken in quitting too quickly.

Put all the cases together and we're left with a far more sweeping conclusion: A politician can weather a storm of scandal and survive. The trick is not to back down. Concede nothing. Refuse to give in. Display no sense of shame or guilt. And before long the storm will pass.

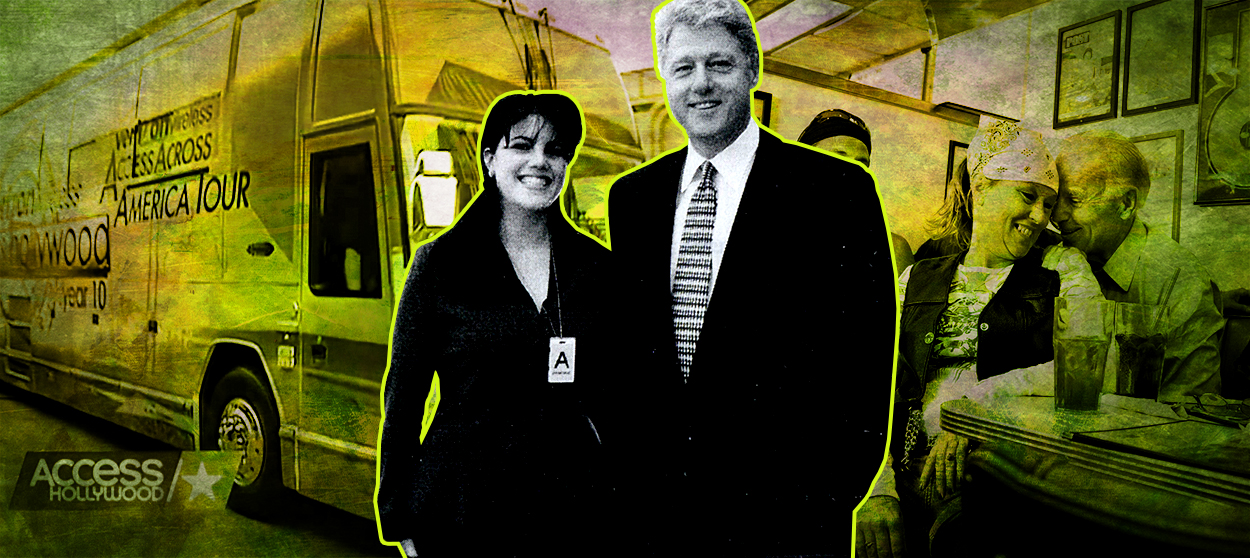

The first politician to demonstrate the capacity to ride out a scandal in this way, even in the face of solid evidence of a misdeed, was Bill Clinton, aided very powerfully by the entire leadership of the Democratic Party. Clinton undeniably lied under oath. He clearly behaved sordidly in the Oval Office with an intern less than half his age. Yet at no point did he or the Democratic leadership concede a thing. Ken Starr's investigation, the shocking details it revealed about Clinton's actions with Monica Lewinsky, impeachment — the president and his fellow Democrats dismissed all of it, ascribing it to a purely partisan crusade against him and his administration. This dismissal, which never wavered, is what separates this episode from Watergate and the Iran-Contra Affair, both of which ended in at least a partial concession of wrongdoing.

And it worked. Clinton survived impeachment. His approval ratings never significantly slipped. He ended his presidency quite popular. And this popularity has persisted through the years.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Why does denial work? A mix of reasons. People have short attention spans, and the ever-accelerating news cycle makes them shorter with every passing year. Then there's the rise of political tribalism and negative partisanship, which incline people to accept bad behavior from their own side; that can predispose roughly half of the electorate to view the news of a scandal with a skepticism that only deepens over time, especially in the face of a strenuous disavowal of the accusation. Finally, there's the all-American love of toughness and victory. As the days drag into weeks after a scandal breaks, the very fact of the politician's survival comes to be taken by many as itself a sign of virtue — an indication that the scandal-plagued public figure actually deserves to prevail. Once that tipping point has been reached, the politician is home free.

The dynamic plays out differently in media, journalism, Hollywood, and the corporate world more generally because of the profit-seeking imperatives of business. Those who run the show are desperate to keep their brands unsullied by bad press and negative publicity.

The question is whether this will remain the case. How long will CEOs, advertisers, and PR firms continue to run away from talent embroiled in scandal when they see over and over again in the political sphere that the public at large doesn't especially care?

Of course some members of the public do care — especially the very-much-online self-styled activists and members of woke Twitter mobs. They can and do generate enormous amounts of heat in response to behavior that violates evolving (and contested) moral norms. But how much damage do those few hundred, or at most a few thousand, social media obsessives really do? How much business do they drive away? In a country of 320 million consumers, and a world of several billion more, do those stoking the scandal really matter? And even if they do, how long will they continue to matter? If a Hollywood studio or magazine publisher knows that, in many cases, the scandal will blow over in a week or a month, why cut and run rather than wait it out?

We like to look down on the sleaziness of politics, and there are more than enough examples to justify this impulse. But the fact is that this sleaziness is a function of what voters reward, tolerate, and fail to punish — and those voters are us, the very same people who consume news and entertainment by the bucketful. Why would we be moral sticklers in one facet of our lives when we're not in another?

The potency of scandal is waning in the political realm. The trend is unlikely to stop there.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.