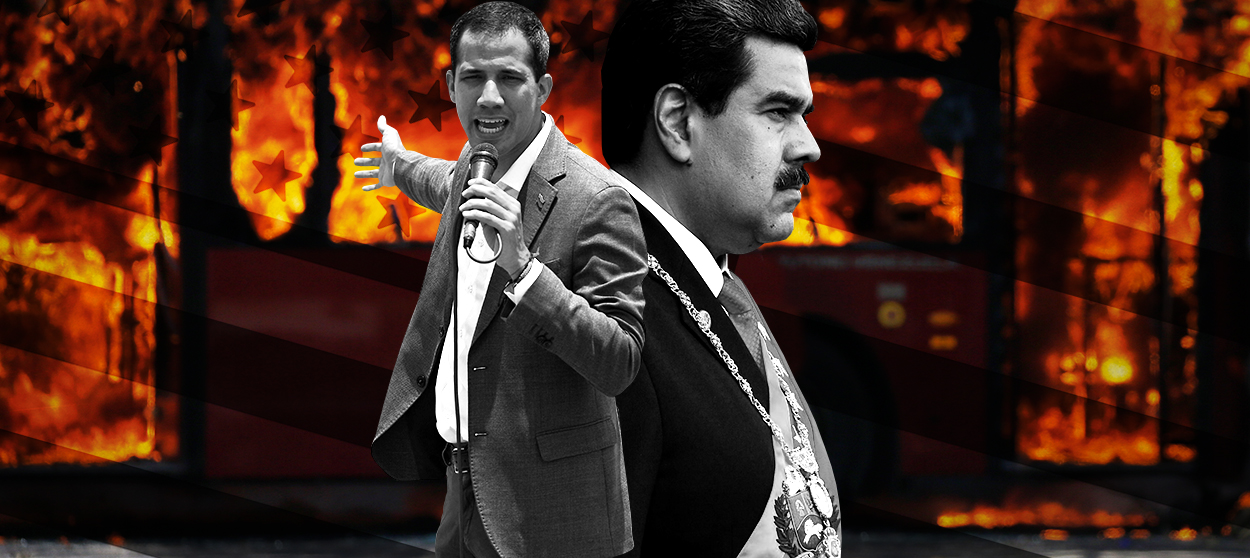

America's coup attempt in Caracas

Why Venezuela would be far better off if it could decide its future without American meddling

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

However events play out in Venezuela over the coming hours, days, weeks, and months, the United States will be to a significant extent responsible for the outcome. This is our baby. We've come out in strong opposition to the government of Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro. We just as strongly backed Juan Guaidó's bid to name himself acting president of the country and rallied other countries to recognize the legitimacy of his claim to power. And it is wildly implausible that Guaidó would have launched his attempted coup without our knowledge and close involvement.

Of course propagandists for the Pentagon would prefer that we not even call it a coup. In their sophistical view, Guaidó's already the leader of the country, Maduro is a lawless usurper, and all Guaidó is attempting to do is bring the facts on the ground into alignment with this reality. But this is an ideologically motivated fantasy. Up until the events of Tuesday morning, Maduro was in control of the Venezuelan government, including its military. Guaidó then attempted to demonstrate that he had some members of the military on his side in order to convince the rest to join him. That's the textbook definition of an attempted coup. As of Tuesday evening, it hadn't worked. If events continue along these lines for much longer, it will be accurate to describe Guaidó's actions as a failed coup.

And regardless of the outcome, the U.S. will be at least partially responsible. We've certainly been here before. It's the story of Cuba, Chile, Nicaragua, and El Salvador repeated now in Caracas. A Latin American government descends into chaos, the United States takes an active interest in the outcome of the unrest, manipulating the people involved, making its preferences clear, issuing threats and working behind the scenes and under cover to control the outcome.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Meddling in the internal affairs of other countries is something empires do, and in this respect the United States is undeniably an imperial power. This was clearer during the Cold War, when the U.S. and its imperial rival and ideological opponent (the Soviet Union) turned the globe into a chess board, carving up spheres of influence, divvying up regions, and picking proxies to wage hot wars in order to push back against each other's ambitions.

Because this contest ended in such an unexpected and lopsided victory for the American side, we were never forced to examine whether all or most of these points of conflict were necessary or even contributed meaningfully to the outcome. Was it really imperative for the U.S. to wage (and fail to win) two costly, ideological wars in East Asia in the middle decades of the 20th century? Did the Chilean coup of 1973, which installed the authoritarian government of Augusto Pinochet, significantly advance our aims against the Soviets? How about the death squads that we supported in Nicaragua and El Salvador during the 1980s as a way of stymieing communist hopes in the hemisphere? Would the Soviets really have held on much longer in Moscow without such efforts and the immense human suffering they produced?

Our efforts to overthrow Maduro seem comparatively benign. He and his dictatorial predecessor, Hugo Chavez, have transformed Venezuela, which sits on the largest oil reserves in the world, into an economic basket case plagued by hyperinflation, food shortages, and collapsing social services. Why shouldn't we intervene in order to overthrow a government marked by malicious incompetence and help install one that might do a better job?

The answer is that it's not our business to do so.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Democracy is a lovely ideal, but it doesn't just imply a set of norms and institutions — free and fair elections, individual rights, an independent judiciary, and so forth. It also involves national self-determination. And this latter standard can't be achieved in a nation when another country attempts to manipulate and control the course of events within it. The Venezuelan people need to decide their fate for themselves. We can hope for the best, and this can include hoping for the successful overthrow of the Maduro government and its replacement by a better one. But as soon as the United States becomes involved, attempting to enact the coup and install a replacement, we poison the process, undermining the democratic legitimacy of the very people we're trying to help.

Now the person or group attempting the coup can be credibly accused of doing the bidding of the United States. If the plotters succeed, this will weaken their authority. If they fail, it will implicate the U.S. in the repression and possible bloodbath to come. Far better to let events unfold of their own accord and then help out after the fact however we can.

But what about the hard-nosed case for intervention — the one based on the need to thwart Russian mischief-making in our hemisphere on behalf of the Maduro regime? Going all the way back to the Monroe Doctrine, first enunciated in 1823, the U.S. has asserted a right to oppose the meddling of world powers from other parts of the globe in the affairs of the Americas. That would seem to justify taking a stand against Maduro and his Russian sponsor.

The problem is that, even if we still wish to define American interests as encompassing the entirety of our hemisphere, we do an extremely poor job of prioritizing the defense of those interests over other pursuits around the globe. In particular, if we want Vladimir Putin to keep his hands off of Venezuela and recognize the legitimacy of our claim to such an expansive sphere of influence (Caracas is over 1,300 miles away from Miami), we should probably be less insistent on expanding NATO far into Russia's historical sphere of influence, and indeed right up to its border.

Russia's effort to meddle in Caracas is partly a function of this tension and double standard on our part — asserting a right to control who does what in our (expansive) backyard while denying the legitimacy of other countries doing something analogous in their own regions, and indeed provoking them with actions meant to show that we couldn't care less what they think. Such behavior severely weakens our hand in any effort to persuade Putin to back off his efforts to shape the course of events to our south.

Venezuela would be better off if both world powers stepped back from playing their imperial games and allowed events to unfold without either attempting to control them. That is what the democratic ideal of national determination truly demands.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’

How to Get to Heaven from Belfast: a ‘highly entertaining ride’The Week Recommends Mystery-comedy from the creator of Derry Girls should be ‘your new binge-watch’

-

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960s

The 8 best TV shows of the 1960sThe standout shows of this decade take viewers from outer space to the Wild West

-

Microdramas are booming

Microdramas are boomingUnder the radar Scroll to watch a whole movie

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred