Why America's strict new anti-abortion laws could backfire

The legislators who pushed restrictive new laws in Alabama and Georgia should be very nervous

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The anti-abortion laws passed in recent days by legislatures in Alabama and Georgia seem designed for one purpose: to get the Supreme Court to overturn its landmark 1973 Roe v. Wade ruling that guaranteed a woman's right to an abortion. The Court — more solidly conservative now than ever thanks to the recent addition of Justice Brett Kavanaugh — may well uphold those new laws.

Will voters do the same?

Maybe not. There is plenty of evidence that citizens of conservative states are, to some extent, actually protective of abortion rights. It may not be something they proclaim in their offices, at church, or to pollsters — but their secret beliefs can become quite evident once they enter the voting booth. This should make the legislators who passed the new bills very nervous.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

My home state of Kansas has been a hotbed of abortion-related activism for more than a generation. Most memorable, perhaps, were the 1991 "Summer of Mercy" protests in Wichita, where thousands of protesters flooded the city to blockade an abortion clinic operated by Dr. George Tiller; over the course of six weeks and more than 2,600 people were arrested. Anti-abortion protests in Kansas have, on occasion, congealed into violence: Tiller's clinic was firebombed in 1986; he was shot and injured by an abortion opponent in 1993; he was shot and killed by another abortion opponent in 2009.

But the state's record on abortion is more mixed than Tiller's story might suggest. Take, for example, the story of Phill Kline, someone you've likely never heard of but whose rise and fall could be a warning sign for anti-abortion legislators in Kansas and other red states today. Kline spent a decade as a culture warrior in the Kansas legislature before being elected the state's attorney general in 2002. He used the perch to go on an anti-abortion crusade, ultimately bringing more than 30 misdemeanor charges against Tiller in 2006. A judge threw out those charges; Tiller was acquitted in a follow-up case the following year.

But voters in the famously red state of Kansas had enough: Kline lost his re-election campaign, badly, with just 41 percent of the vote. He managed to get himself appointed as district attorney in Johnson County, home to prosperous Kansas City suburbs, only to lose a primary election two years after that. These days, he's on the faculty at Liberty University in Virginia, having lost his law license for misconduct during the abortion investigations.

Kansas is hardly a progressive state, but voters here often tire quickly of extremists. The same is probably true in other conservative states. While America's abortion politics are polarized, many citizens are closer to the mushy middle on abortion — morally squeamish about it, but sometimes willing to suspend those qualms when faced with difficult decisions for themselves or their family members.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Across the nation as a whole, just 17 percent of Americans say Roe should be overturned entirely, and this reality is reflected at the state level: In 2008, voters in the solidly-Republican state of South Dakota overwhelmingly rejected a statewide ban on abortion — and repeated the feat two years later, even after exceptions for incest and rape were added to the proposed law. In 2011, Mississippi voters rejected a similar referendum by an even larger margin. Back in my home state of Kansas, the state Supreme Court last month ruled — shockingly — that the state constitution protects the right to an abortion.

"There's a lot of public pressure to be anti-abortion," Marvin Buehner, a South Dakota OB-GYN said at the time of the 2008 proposal. "People are more likely to answer the poll that they'll support [a ban]. Then they get into the ballot booth and decide they just can't vote for something like that."

These sweeping new laws do very little to assuage the concerns of such voters. Alabama's bill, for example, makes no exception for incest or rape. Georgia's law would grant personhood protections to fetuses just six weeks after conception. Even if the Supreme Court upholds the laws, the examples from Kansas, Mississippi, and South Dakota suggest that legislators who passed these new bills could find themselves suddenly vulnerable.

Of course, that won't satisfy pro-choice women and men who believe the right to abortion is just that — a right, to be defended by government, not compromised by it. "Today's women can only thrive in a state that protects their most basic rights — the right to choose when and whether to start a family," Andrea Young, executive director of Georgia's ACLU, said last week, pledging to challenge the state's new law.

Despite the high stakes of the coming court battles over the new anti-abortion laws, the Supreme Court is not the end of the line. In politics, few battles are ever completely won or lost. Nearly 50 years after Roe v. Wade, the fight may just be beginning anew.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymander

Supreme Court upholds California gerrymanderSpeed Read The emergency docket order had no dissents from the court

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

How robust is the rule of law in the US?

How robust is the rule of law in the US?TODAY’S BIG QUESTION John Roberts says the Constitution is ‘unshaken,’ but tensions loom at the Supreme Court

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’

The ‘Kavanaugh stop’Feature Activists say a Supreme Court ruling has given federal agents a green light to racially profile Latinos

-

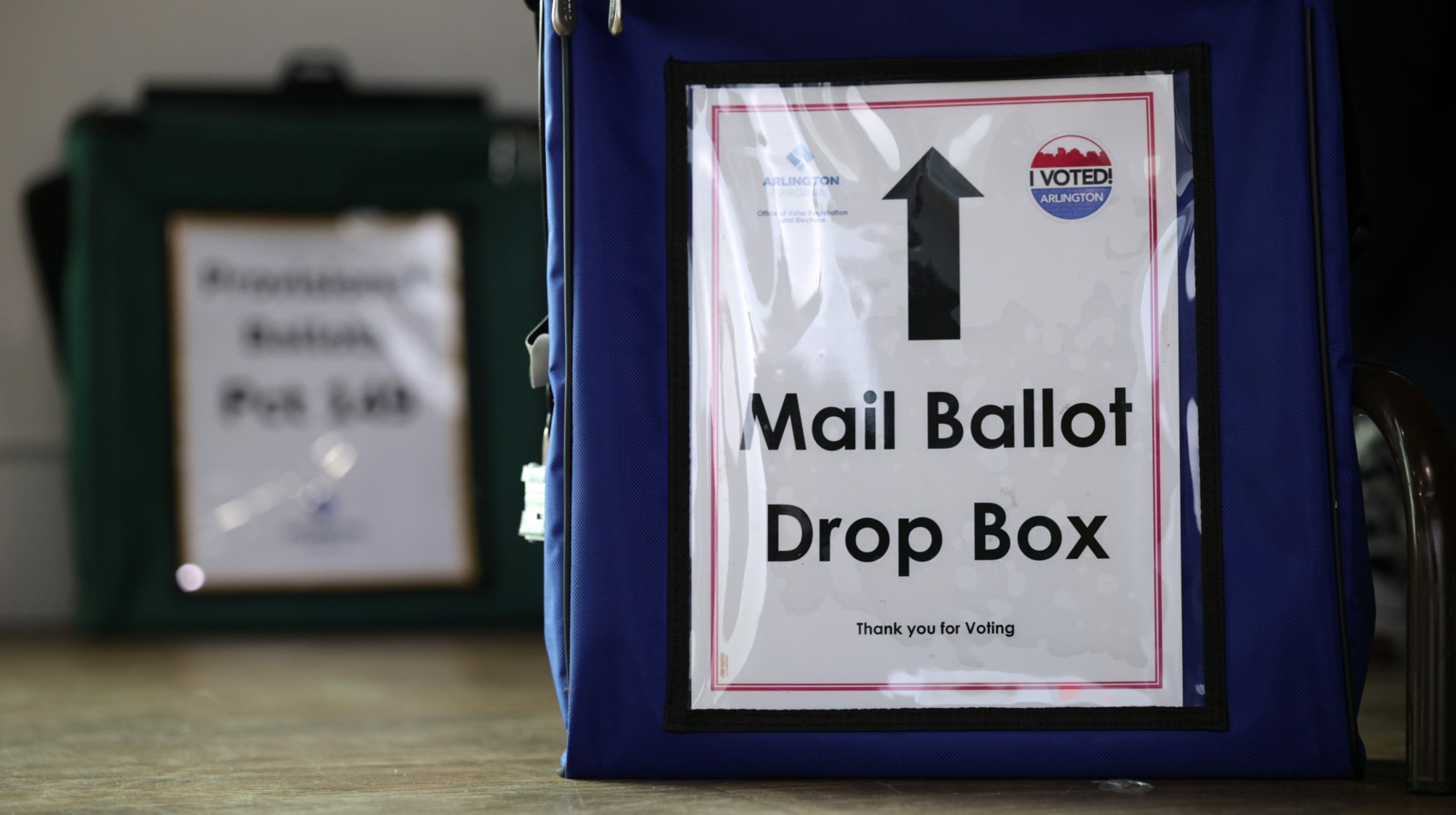

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limits

Supreme Court to decide on mail-in ballot limitsSpeed Read The court will determine whether states can count mail-in ballots received after Election Day

-

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme Court

Trump tariffs face stiff scrutiny at Supreme CourtSpeed Read Even some of the Court’s conservative justices appeared skeptical

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party