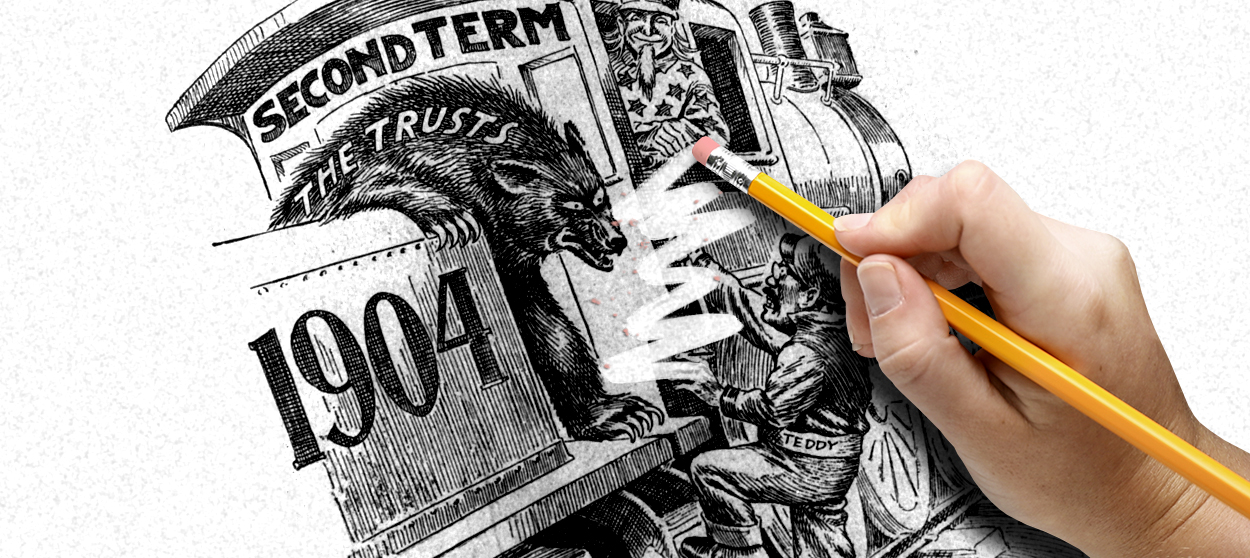

What we lose when we lose political cartoons

The New York Times' decision to cut cartoons is a sad moment for journalism

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

In a cheeky 2012 cartoon by Daryl Cagle, a dog lifts its hind leg for the wind-up. "The Times has no credibility — and no cartoonist," a black speech bubble leaks from its mouth, "but it's still good for something."

Up until this week, though, the overseas edition of The New York Times had soldiered on, employing the publication's only two remaining political cartoonists. Patrick Chappatte and Heng Kim Song's tenure came to an abrupt end late Monday, however, when the editorial page editor James Bennet announced that the Times was "bringing [the global] edition into line with the domestic paper by ending daily political cartoons." Seven years after Cagle's illustration, his dog's lambasting of the Times seems brutally on point. With the annihilation of its editorial cartoon section, the paper gives up one of journalism's — and democracy's — greatest weapons.

Although Bennet claimed the paper had been mulling eliminating the section for "well over a year," the timing seems suspicious to some. In April, the Times had published a cartoon of President Trump walking Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu like a dog; in its apology, the Times rightfully identified the illustration as "clearly anti-Semitic and indefensible." The paper then sweepingly "suspended the future publication of [all] syndicated cartoons," from which the offending image had been pulled; then, only two months later, Bennet announced the paper's last vestige of commitment to editorial cartoons was being erased, too. "I'm putting down my pen, with a sigh," blogged Chappatte in a must-read post about his editor's decision. "That's a lot of years of work undone by a single cartoon — not even mine — that should never have run in the best newspaper of the world." (Chappatte, it should be noted, is one of many cartoonists from around the web to be featured in The Week's free political cartoon newsletter).

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The incident at the Times is only the latest reason to feel concern about the state of political cartoons in this country. Once a deeply-ingrained part of American journalism, there were some 2,000 working editorial cartoonists at the start of the 20th century. In a 2012 special report by the Herb Block Foundation (named for the legendary cartoonist who coined the term "McCarthyism"), fewer than 40 staff cartoonists were found to be employed by U.S. newspapers, a number that is no doubt smaller today. It is particularly a shame because editorial cartoons exercise a freedom that sets the United States apart from other countries: "Cartoons can jump over borders," noted Chappatte in his post. "Who will show the emperor Erdogan that he has no clothes, when Turkish cartoonists can't do it?"

Editorial cartoons' courting of controversy is often a positive and democratizing force, one that rightfully makes people in power squirm by casting motives into sharp relief. It can also come at great risk to the artists: Most famously, 12 people were killed in 2015 when terrorists opened fire on the newsroom of the French satirical newspaper Charlie Hebdo, ostensibly over the paper's cartoonish depiction of Muhammad.

This can come with a negative side too, as it's not totally uncommon for hateful images to make it into print in the guise of political cartoons: The unnecessary anti-Semitic depiction of Netanyahu is one of a few recent examples, including a "racist" depiction of Serena Williams that was recently published in Australia, and a New York Times editorial animation of Trump and Putin was widely criticized as homophobic by critics. Still, such mistakes, while deeply regrettable, should not cloud the important work that many other cartoonists do.

A truly great editorial cartoon, rather, should be the knife-twist of accountability. While reported articles keep the powers that be in check, and opinion and editorial sections help readers make sense of that reporting, editorial cartoons are the jolt that shocks you into caring. Many people find them so vital to the journalistic process that there are calls to put them on the front page. To lose them, then, is to lose one of the most powerful wakeup calls we have available to us as readers. Where would we be without Robert Minor's succinct anti-war illustration of a headless man, declared by an army medical examiner to "at last" be "a perfect soldier?" Or without Benjamin Franklin's dissected snake urging the states to "join, or die," often cited as America's first political cartoon and a pivotal rallying cry ahead of the Revolutionary War?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

It really should be the golden age of political cartoons, too. Not just because of the ample material, but because social media caters to our limited time and attention, and single-panel images are easily shared and understood within moments of reading them. The occasional viral political cartoon proves the point, such as Pia Guerra's chilling picture of Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School security guard Aaron Feis being welcomed into the afterlife by countless victims of mass shootings. Political cartoons are taking on new forms to adapt to the digital era, too, as found in the great work coming out of The Nib, or webcomics like K.C. Green's dog that reacts to his house burning down with the addictively-quotable proclamation "this is fine."

Still, there is a worrying drought of editorial cartoonists, and the Times' move this week is the wrong one, regardless of whether it was truly long in the making or a knee-jerk response to an unfortunate event. As cartoonist Ted Rall told NPR in 2008, the members of his profession are "the canaries in the coal mine" for the newspaper industry and, in turn, for the state of American democracy. "Maybe we should start worrying," is how Chapatte puts it in his post. "And pushing back. Political cartoons were born with democracy. And they are challenged when freedom is."

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.

-

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on track

The Olympic timekeepers keeping the Games on trackUnder the Radar Swiss watchmaking giant Omega has been at the finish line of every Olympic Games for nearly 100 years

-

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?

Will increasing tensions with Iran boil over into war?Today’s Big Question President Donald Trump has recently been threatening the country

-

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the president

Corruption: The spy sheikh and the presidentFeature Trump is at the center of another scandal

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred