When will a white man say what Ta-Nehisi Coates said?

We shouldn't need black people to recount the horrors of slavery for us

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How can it be that, in 2019, writer Ta-Nehisi Coates was forced to give testimony in front of the House Judiciary Committee that sounded like it could have been given in front of the Joint Committee on Reconstruction in 1866? How is it that, more than a century and a half after the end of the Civil War, a black man had to instruct members of the United States Congress on the rudiments of slavery and its legacies?

How can it be that, rather than participating in a national reckoning like those provided by South Africa's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, or Germany's many post-war acts of national self-reflection and atonement, America is barely humoring the idea of paying reparations to the descendants of former slaves?

Most importantly, why oh why are powerful white men still pretending to listen instead of saying what needs to be said? When will a white man sit where Coates sat yesterday and address black people in the manner he spoke to those white representatives, and by extension white America: without the buffer of mediating, academic language, bluntly, poetically, vividly, humanely and unforgivingly, eye-to-eye, person-to-person, unafraid of the truth?

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

When will a white man speak to black America and say, "Here's what we did: we hunted you. We trapped you. We tore you from your mother's arms and called you cargo.

We beat you. We put you in a crouch under an all-day sun and deformed you. We forbid you to read. We lashed your skin with salted leather if you read, or dared to stand up. We took your son from the arms of his mother, and burned you alive if you protested. We murdered you.

We murdered your children. We left your daughters to die in the mud after birthing our children. We branded your children like beasts. We crushed the bones of your children's hands with the weight of these great buildings they raised. We celebrated these buildings as our accomplishment.

We wrote laws in these buildings forbidding your grandchildren to vote, or read or keep a family together or enter the buildings they built. We mocked them for not being able to do those things. We dared your grandchildren to vote, or love, or read. We drowned them or hung them when they tried to do those things. We told stories of their ignorance and wickedness when they didn't try.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

We drew lines around your great-grandchildren's water fountains and bus seats, bright red-lines around their neighborhoods, to keep our money out. We taunted your great grandchildren with dreams. We told them what to dream, then mocked them for dreaming those dreams. We shackled their hands with their bootstraps. We flailed our arms and balled our fists and reddened our faces in roaring incomprehension that they didn't have jobs, or know the value of an education. We murdered them. We wished we didn't have to murder them, though, so that should count for something.

We burdened them with our fear. We dropped the unmeasurable weight of our failures onto them and laughed when they bent their spines. We insisted they straighten up. We laughed at their names and erased their faces. We stole their expressions of pain and called them our own. We warped them into the shape of our nightmares, swollen to the size of demons, and feared for our lives instead of theirs. We sighed about this on occasion.

We pretended to not understand your great grandchildren. We wondered what their problem was, and we murdered them. We murdered them by crooking our fingers, for putting their hands in their pockets.

And we wanted you to get over it.

We sleep on a mountain of bones. Every load we lift has been made lighter by generations of broken black hands. Every dollar we spend is soaked in the sweat of untold centuries' worth of demeaned and invisiblized people. We travel through life on paths cleared by people of color yet named after white men, men who in turn conscripted still more people of color to the job of genuflecting at their faux self-awareness. Men like me.

The crime is ongoing. It is the engine of our success and will only stop when the wheels are jammed. I am here to throw myself on the wheels. The day of reckoning has come.”

When?

Peter Birkenhead is a writer who lives in Washington, D.C. His work has appeared in The Washington Post, The Daily Beast, the Los Angeles Review of Books, and other publications. He is the author of Gonville, a memoir published by Simon & Schuster.

-

Companies are increasingly AI washing

Companies are increasingly AI washingThe explainer Imaginary technology is taking jobs

-

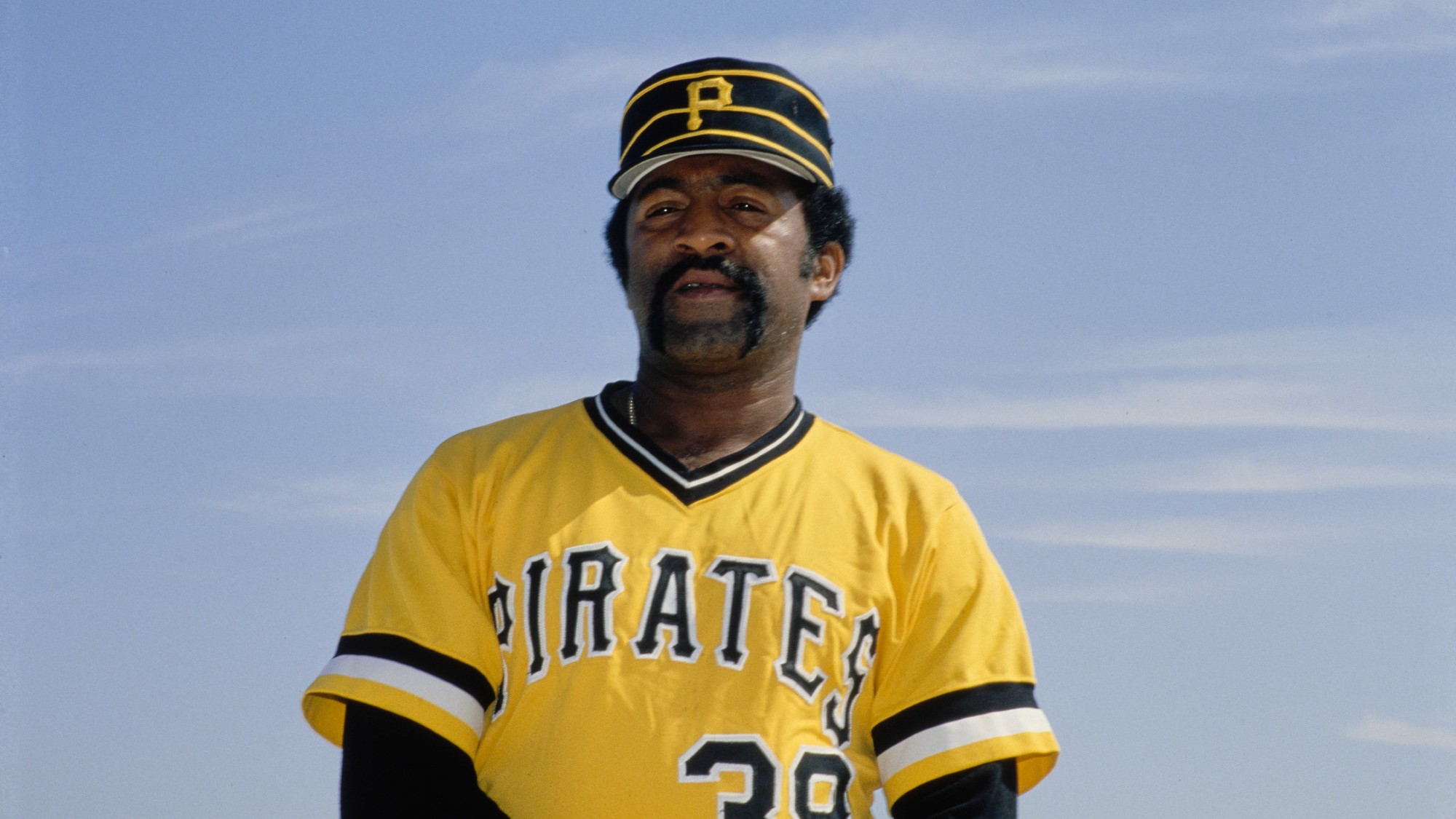

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Fame

The 9 best steroid-free players who should be in the Baseball Hall of Famein depth These athletes’ exploits were both real and spectacular

-

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’

‘Bad Bunny’s music feels inclusive and exclusive at the same time’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred