Trump is an apocalypse

The original meaning of apocalypse is a moment of exposure. Seeing it can feel like the end of the world.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The last book of the Bible is an apocalypse. We call it "Revelation" in English, but in the Greek it's apokalypsis, as in, the "apokalypsis of Jesus Christ ... to his servant John."

Apokalypsis does not mean "catastrophe." There is plenty of that in Revelation, but our use of "apocalypse" as a synonym for world-ending disaster is the result of this book, not the other way around. Apokalypsis is a literary genre our culture has abandoned, and it simply means "revealing." (Thus, "Revelation.") The concept is one of unmasking, of unveiling a previously hidden truth. The display is necessary, but that doesn't make it happy. Seeing it can feel like the end of the world.

Apokalypsis is a moment of exposure, a paradigm shift. It's suddenly realizing you were in the wrong. It's finally admitting a relationship is over. It's turning on the light and seeing cockroaches scatter.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

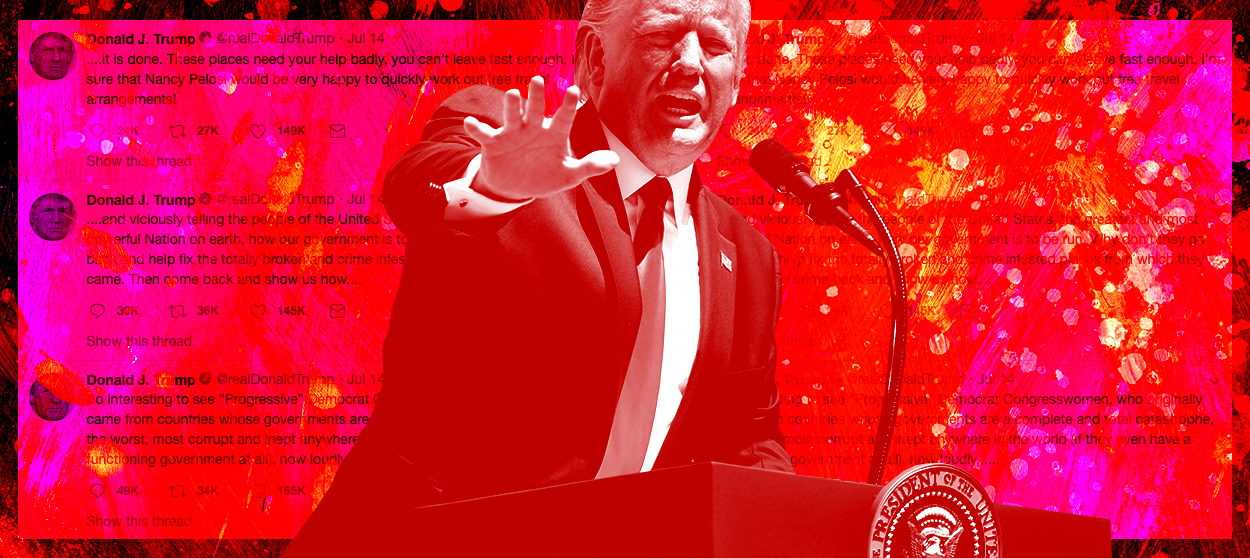

President Trump is an apocalypse.

"The most useful thing about Donald Trump is that he coaxes many people into revealing their worst character traits in defense of him," tweeted Corie Whalen, a freelance writer and former communications director for Rep. Justin Amash (I-Mich.), after the president's go back to where you came from remarks. "I've learned a lot of terrible things about many folks I was once comfortable associating with," Whalen added. "I'm a whole lot more cautious now."

Regardless of whether and how politics should rejigger our relationships, Trump's apocalypse will surely elicit the impulse. The four years since he rode that golden escalator into our national consciousness have often been described as "polarizing," and that's not wrong. But much of the discord over Trump we're experiencing is not new movement to political extremes but a revelation of what was already there. Trump has surely catalyzed division in our polity, but I suspect he has done much more to merely expose realities previously unnoticed, hidden, or ignored.

This clarifying effect is evident, as Whalen wrote, where Trump's Republican defenders are concerned. Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.) is a case in point.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Before Trump, Graham's infinite hawkishness was his defining political feature. It was and is a disgraceful motivating principle — I mean, what kind of person responds to national war weariness with, "Well, don't vote for me"? — but pre-Trump Graham seemed to operate out of a concern for Americans' security, however unethical and impractical his methods. He militated against Trump's candidacy on foreign policy grounds, claiming Trump's occasional anti-interventionist instinct would "lead to another 9/11."

Trump's immigration policies, and especially his campaign announcement slurs about Mexican immigrants, were another sticking point for Graham, whom Rush Limbaugh once dubbed "Lindsey Grahamnesty." "When Donald Trump says that most of these people are drug dealers and rapists, what you're telling [hypothetical Hispanic American] Sgt. Gomez is his mother, his older brother, his father, in the eyes of at least one Republican, are a bunch of bad people," Graham said. "Why would any group vote for a party who embraces that? I sure as hell wouldn't."

Today he sure as hell would. Graham has emerged as one of Trump's most vigorous defenders, gamely showing up to interviews after each new outrage to offer some small caveat about personal disapproval before launching into a steadfast apologia for the president. His goal, Graham explained in an unexpectedly candid talk with The New York Times Magazine, is "to try to be relevant," which is a nice way to describe craven pursuit of power.

Graham arrived on cue in the go back to where you came from controversy, calling the minority representatives Trump targeted "a bunch of communists" who "hate our own country." His only critique: The president should focus a bit more on policy. A few years ago, Graham was calling Trump a "race-baiting, xenophobic, religious bigot" for comments like these. Now he's just got messaging tweaks.

This is apokalypsis. The cockroaches are visible.

The president is also a source of revelation about his enemies. Think of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) and her steadfast refusal to launch impeachment proceedings (or even a symbolic vote of censure) against Trump or any of his secretaries despite her Democratic majority. For all her fiery rhetoric about the president as a racist, fascist criminal who must be removed from Washington, Pelosi declines to exercise her branch's constitutional oversight authority.

"I know that aggressive oversight, especially impeachment hearings, is a politically fraught decision, full of risk," notes New York magazine's Andrew Sullivan in a thorough dissection of Pelosi's choice. But if "she doesn't act against a serious threat to the Constitution," he continues, "voters will infer that the Democrats don't actually believe there's a threat."

Or perhaps they will infer that the gravest threat Pelosi perceives is not Trump's retention of power but her loss of it. Whatever happens, her response to Trump is apokalypsis.

To the extent that he has permanently changed our politics — and it is difficult, at this point, to envision what a post-Trump political and media climate will be like — this revelation will continue after Trump leaves office, whenever that may be. Once uncovered, these realities won't be rehidden. Neither must we let them be forgot.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred