The value of Marianne Williamson

Her answers may be flimsy, but she's asking the right questions

Enough for one day about what Joe Biden said in response to what Kamala Harris argued about her plan after receiving criticism from, I don't know, someone, maybe Bernie. Instead, let's acknowledge what internet memes are already suggesting: namely, that the most interesting candidate seeking the Democratic presidential nomination is Marianne Williamson, the author and spiritualist guru currently polling at around 0.4 percent.

When I say that she is the most "interesting" candidate I do not mean to suggest that Williamson has a good chance of winning or that she is likely to exercise a serious influence on the direction of her party in the next year and a half. For all I know, her campaign, such as it is, is a Russia-funded psy-op, as Jill Stein's independent bid for the presidency in 2016 largely was.

What matters about Williamson is not the likelihood of her becoming president, but what she has to say to the American people, for its own sake.

Subscribe to The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Don't misunderstand me. Williamson's books and speeches are not intellectually distinguished. They are, in fact, full of the worst kind of New Age mumbo-jumbo. But it would be a mistake to dismiss her out of hand for this reason, not least because it means conceding that the language spoken by the average politician of either party — neoclassical economics, with its fabulous bestiary of "margins" and "rational actors" and "indifference curves" — is not itself anagogical gibberish straight out of The Golden Bough. Williamson's conceptual tools might be poorly made, but they are meant to repair things that the vast majority of American politicians, left, right, and center, do not even recognize as broken.

A good example of this was her recent conversation with CNN's Anderson Cooper on the subject of antidepressant medication. What Cooper seemed to want to argue with her about was the value and efficacy of such drugs according to "the data," and whether, for example, they are occasionally overprescribed. Williamson responded by suggesting that what we now identify as "depression," a purportedly non-optimal imbalance of certain chemicals in the brain, is actually an important, indeed essential part of what it means to be a human being. Cooper was less outraged than baffled. (He was not alone.)

The idea that suffering is valuable, that enduring pain is both inherently virtuous and conducive to the development of virtue is one of the very oldest ideas. It is, among other things, one of the central teachings of the Christian religion, which instructs its adherents to bear wrongs lightly because in suffering they unite themselves with the crucified God. It is a hallmark of classical Stoicism, of Buddhism, and hundreds of other significant traditions and thinkers. It is also totally at odds with everything that people in the neoliberal late-capitalist West have been told their entire lives. There is no ill, from a sprained ankle that can be put under an MRI to a terminal disease that can be ended by clinically supervised suicide, that should and cannot be done away with by spending money. Suffering does not belong to the natural order, and society's most fundamental task is its elimination.

This is not a new idea either, but it is one that has never had more cultural currency than it enjoys at present, when it is the closest thing we have to a baseline political consensus. Politicians across the spectrum propose different answers — lower taxes, universal pre-K, the Freedom Dividend, allowing people to buy unpasteurized milk at their local supermarket — but the question is always the same.

Williamson wants us to consider the possibility that because the question — this one and virtually all the other ones too — is wrong, all the answers to them are bound to be at best inadequate and at worst evil. This is why she insists over and over again in the debates that wonkish policy debates are not enough. A Band-Aid, even an expensive one, will not cure a diseased body-politic.

When Williamson says that the single most important force in politics is the power of love, she is probably parroting a Joni Mitchell b-side. But she is also echoing St. Augustine and Dickens and, perhaps especially, Wagner. A basic paraphrase of Der Ring des Nibelungen could easily serve as a gloss on her campaign: Our corrupt social order exists because it was founded on a lie, the lie that love can be traded away for power, and that it is not by the sheer force of will capable of seizing power but rather by the renunciation of power that the present way of things will be overturned and a new order based on love created.

This is one reason that it should not be surprising that, despite her knee-jerk liberal views on issues such as abortion, Williamson has attracted the (admittedly half-ironic) interest of many Catholics. She is (with the possible exception of the freshman Republican senator, Josh Hawley) practically the only American politician who is trying to articulate a vision of the common good, one that is not merely the aggregate of the good of 370-some million people colliding randomly but rather a good that is truly shared by a whole society united in love to pursue ends that transcend anything from which any of us might benefit individually.

I for one welcome Williamson's impossibly weird but incredibly righteous affirming flame.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.

-

El Palace Barcelona: old-world luxury in the heart of the city

El Palace Barcelona: old-world luxury in the heart of the cityThe Week Recommends This historic hotel is set within a former Ritz outpost moments from the Passeig de Gràcia

-

The best history books to read in 2025

The best history books to read in 2025The Week Recommends These fascinating deep-dives are perfect for history buffs

-

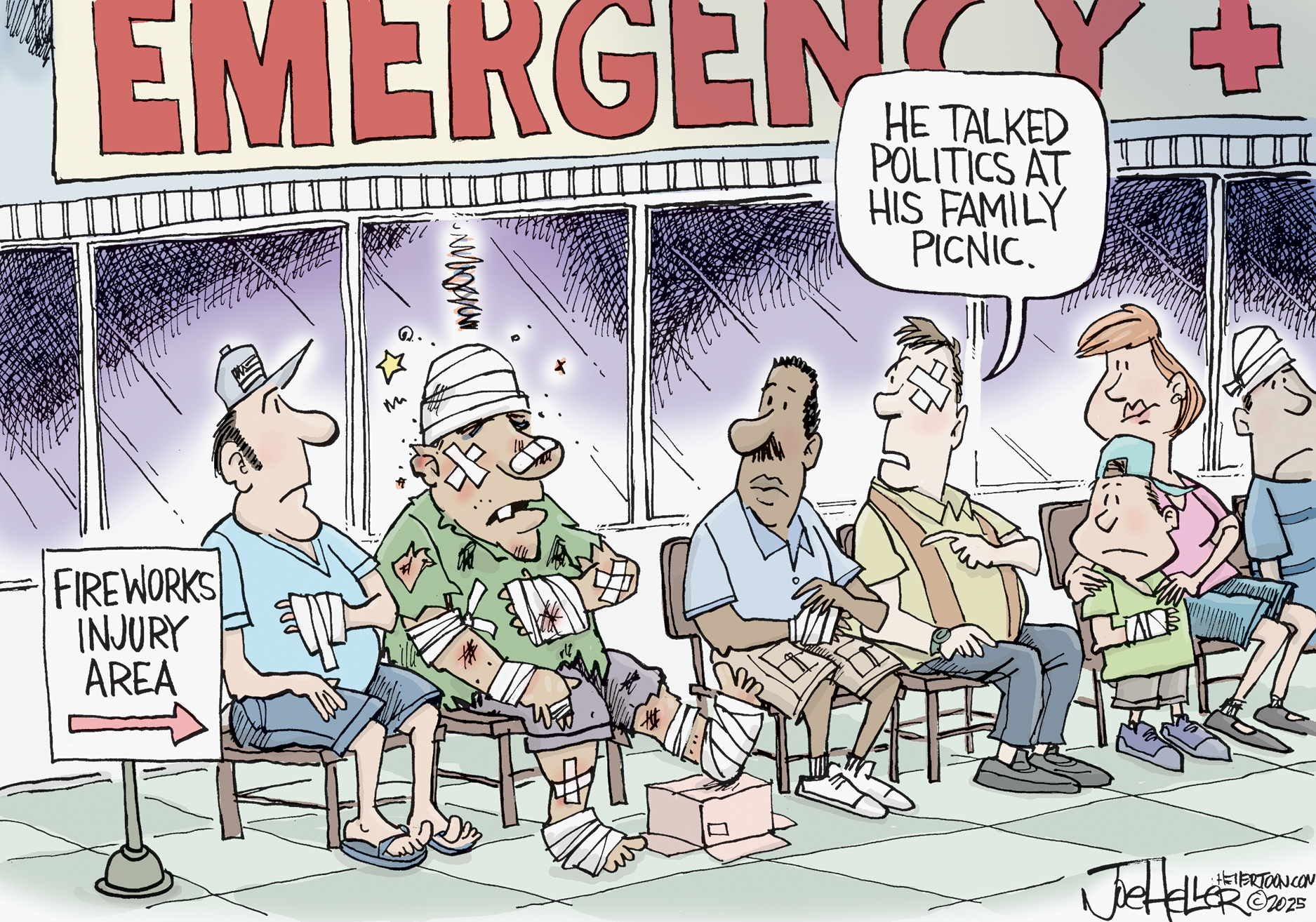

July 4 editorial cartoons

July 4 editorial cartoonsCartoons Friday’s political cartoons include the danger of talking politics at a family picnic, and disappearing Medicaid entitlements

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred

-

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?

Will Trump's 'madman' strategy pay off?Today's Big Question Incoming US president likes to seem unpredictable but, this time round, world leaders could be wise to his playbook

-

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?

Democrats vs. Republicans: which party are the billionaires backing?The Explainer Younger tech titans join 'boys' club throwing money and support' behind President Trump, while older plutocrats quietly rebuke new administration

-

US election: where things stand with one week to go

US election: where things stand with one week to goThe Explainer Harris' lead in the polls has been narrowing in Trump's favour, but her campaign remains 'cautiously optimistic'

-

Is Trump okay?

Is Trump okay?Today's Big Question Former president's mental fitness and alleged cognitive decline firmly back in the spotlight after 'bizarre' town hall event

-

The life and times of Kamala Harris

The life and times of Kamala HarrisThe Explainer The vice-president is narrowly leading the race to become the next US president. How did she get to where she is now?