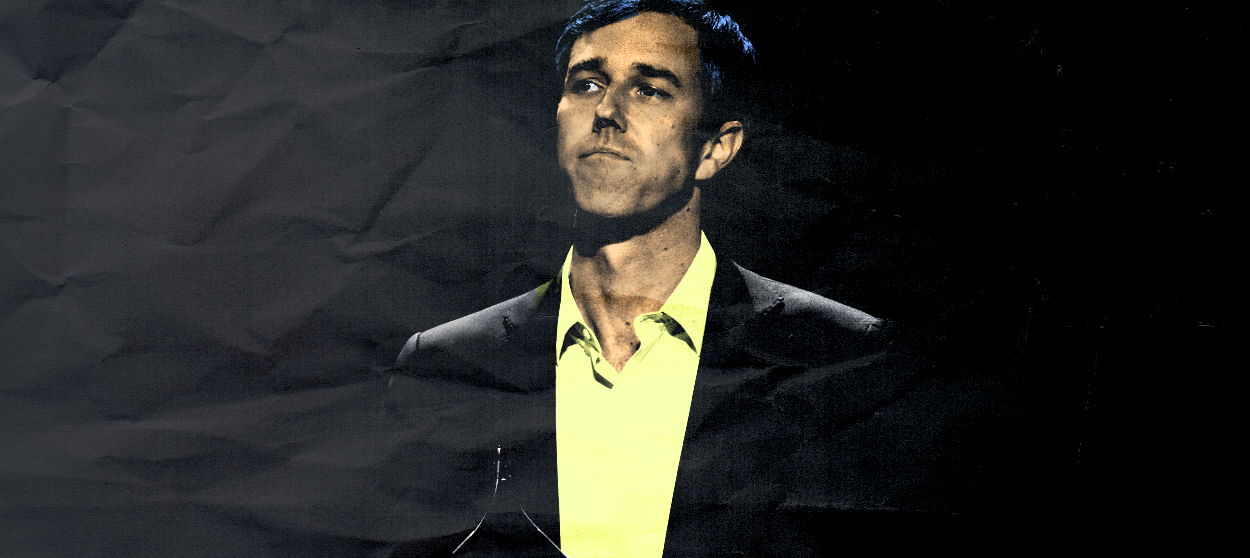

Why Beto O'Rourke's gay marriage idea collapses under scrutiny

Think about how many religious institutions — from mosques to historically black churches to Catholics hospitals — would lose their tax exempt status under his latest brain wave

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Any religious group that does not support gay marriage should not be tax exempt, Democratic presidential candidate Beto O'Rourke argued Thursday night. "There can be no reward, no benefit, no tax break for anyone, or any institution, any organization in America that denies the full human rights and the full civil rights of every single one of us," he said. "As president, we're going to make that a priority, and we are going to stop those who are infringing upon the human rights of our fellow Americans."

The line got applause at CNN's Equality Town Hall, as O'Rourke could have anticipated. But in the broader polity, it simply doesn't hold up to scrutiny. Whatever one thinks about gay marriage — and tax exemptions for religious institutions, for that matter — this is a bad idea. It's flagrantly unconstitutional content discrimination. It's a shortsighted political strategy that will not play so well in the general election. And, realistically, it could do serious harm to vulnerable people being served by the religious institutions whose finances O'Rourke would assail.

The constitutional problem is simple: The federal government cannot mete out benefits or punishments on theological grounds. As Cato Institute legal scholar Walter Olson explains at Overlawyered, "a long line of court opinions has made clear that ... 'tax exemptions can't be denied based on the viewpoint that a group communicates.'" The law can make distinctions based on group behavior or "for deliberately engaging in speech that falls within one of the few narrow exceptions to the First Amendment, such as true threats of criminal attack, or incitement intended to and likely to cause imminent criminal conduct," but not for simple belief, even of very offensive tenets.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Supreme Court has come down hard on federal efforts to manipulate religious institutions' internal decision-making processes; in 2012, for example, the justices unanimously struck down an Obama administration attempt to interfere in church hiring for ministerial roles. This means that whatever O'Rourke says about making his proposed change "a priority," he would face a steep uphill legal battle. That legal reality isn't debatable, and it turns O'Rourke's position into empty grandstanding. It's also a safeguard that works both ways: If a President O'Rourke can strip nonprofits of tax exemptions based on their beliefs, so can a President Trump.

Then there are the political ramifications. Obviously, O'Rourke's proposal has its constituency, but consider how this will play among American voters more broadly. It is tailored for Republican attack ads appealing to independents. As with gun control, O'Rourke says aloud exactly what the GOP has warned Democrats secretly want to do.

Nixing these tax exemptions would affect a much larger spread of religious institutions than we might immediately realize. O'Rourke may be picturing ending the tax exemptions of spiteful cults like Westboro Baptist Church or even more run-of-the-mill conservative, white evangelicals who probably voted for Trump. But those would hardly be his only targets.

Gay marriage still has minority support among black Protestants, meaning many historic black churches — to say nothing of religiously-affiliated HBCUs — could lose their tax exemption under O'Rourke's plan. The same is true of American Muslims, who in O'Rourke's scenario would find themselves beset by federal discrimination from the political right and left alike. (Indeed, the religious content discrimination O'Rourke wants is arguably constitutionally similar to the discrimination of Trump's original "Muslim ban.") Also affected would be religious social service organizations, such as the Catholic hospitals which serve one in six patients in the U.S. and in many areas offer the only hospital care available.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A slight majority of American Catholics — like O'Rourke himself — support same-sex marriage, rejecting their church's formal stance, and so do substantial minorities of other religious groups with official doctrinal opposition. But that difference of opinion does not mean these voters want to see their churches, mosques, or other religious institutions losing their tax exemptions. And a content-neutral abolition of these tax exemptions, while likely easier to get past the Supreme Court, would only mean more angry religious voters, as even LGBTQ-affirming religious institutions would find themselves in significant financial difficulties.

Those financial consequences would not be limited to congregants of the targeted churches in O'Rourke's vision. "Do we really want to shut down an entire part of the education sector or social services sector?" asked Michael Wear, who directed outreach to religious voters for former President Barack Obama's 2012 campaign, in an interview on the CNN town hall with Deseret News. "I would hope the answer would be no."

I would hope so too, because Wear isn't exaggerating. Those Catholic hospitals are just one part of an extensive religious social service infrastructure that serves millions of Americans of all faiths every day. You may think this isn't how it should be — perhaps you want all social services to be nonsectarian or handled by the state — but that doesn't change the current reality, nor does it reflect the desires of many other Americans who support and benefit from these organizations. If all the religious nonprofits with doctrinal opposition to gay marriage lose their tax exemptions, vulnerable people will suffer as a result. The effects would not be limited to white, Republican Protestants. In fact, it would almost certainly do tangible harm to some of the very gay Americans whom O'Rourke purports to protect.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred