The Republican gamble on absolute cynicism

Friedrich Nietzsche would love this GOP

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It's a strange thing to behold America's conservative party eagerly embrace absolute cynicism, but here we are.

In the public impeachment hearings that began Wednesday with testimony from William Taylor, chargé d'affaires at the U.S. embassy in Ukraine, and George Kent, assistant secretary of state for European and Eurasian affairs, Americans saw two very different modes of comporting oneself in public life.

The Democrats in charge of the proceedings, along with the two career civil servants who pride themselves on having worked for a long line of administration of both parties, struck a tone of high-minded gravity. They weren't pursuing political self-interest or vendettas. They were fulfilling their solemn, constitutionally mandated duty to investigate and possibly punish abuse of power and potential criminal activity by the president of the United States. They came merely to provide facts. They weren't taking political sides at all.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The Republicans were having none of it. The members of the majority and the witnesses they had called to testify were rank partisans prosecuting a "scorched-earth war against President Trump." The hearings were a "sham circus." The testimony was "pitiful, ignorant, insubordinate gossip" providing "no trustworthy information." All told, it was a "sad day for the country."

The Republican position — denying the possibility of placing country above party, treating every effort to appear fair-minded, public spirited, and patriotic as an effort to conceal baser and more narrowly political motives — would be a lot easier to dismiss if it didn't have so many intellectually impressive defenders, from the sophists of ancient Athens on down to Friedrich Nietzsche in late 19th century Europe.

This tradition has consistently maintained that every public (and perhaps even every private) statement and action, no matter how gravely high-minded, is ultimately an expression of the will to power — the will of the stronger to impose itself on the weaker, in part by portraying itself as rising above mere partisanship, mere self-interest, mere victory. The sophists made their living by teaching this truth to the wealthy of Athens, instructing them in how to see through the pious nonsense of the politicians and use rhetoric to pursue their own ambitions and acquire political power by manipulating the masses. Nietzsche's aim was somewhat different, preferring to expose the pretense to high-mindedness in order to rid the world of "the spirit of gravity" he believed was discouraging the playful free exercise of the will to power among the most vital and creative among us.

Republicans have made very clear that, following the example of their mob-boss president, they now accept the key assumptions of this potent and resilient tradition of sophistry. In their view, there is no possible transcendence of political self-interest, no rising above the fray in the name of the public good or the national interest. Even a lifetime of working competently and loyally for presidents of both parties is insufficient to demonstrate genuine fair-mindedness or impartiality. If the supposedly dispassionate civil servant points an accusatory finger at our guy, then this act alone demonstrates his dishonesty and narrowly political agenda. That our guy might actually be corrupt is prima facie impossible.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

One reason why Republicans are able to hold, if not gain, political ground with such claims is that they aren't unambiguously wrong. (If sophistry were entirely nonsense, it would have died out quickly, with its ancient defenders long forgotten.) The evidence in favor of political cynicism is real. It could even be seen during Wednesday's hearings. As The New York Times noted in its coverage, the grave demeanor of Adam Schiff, chairman of the House Intelligence Committee, was to some extent scripted — an effort "to reassert some gravity on what might have devolved into Romper Room."

Beyond that, there was the strange decision of both Taylor and Kent to focus in their testimony less on Trump's corruption than on his divergence from what they consider to be the Washington consensus on Russia (bad) and Ukraine (good). That made it sound at times like the Democrats and these ostensibly extra-partisan civil servants are working to impeach and remove the president over a foreign policy dispute.

That plays right into the GOP's sophistical critique of the whole process — though their own sophistry prevents them from convincingly exploiting it.

Trump isn't facing an existential threat to his presidency because he was trying to enact a foreign policy that Democrats and members of the diplomatic corps dislike. If Trump had taken office and tried, with the help of competent and informed advisers, to change American policy in Eastern Europe so that it was more positively disposed to Russia and more suspicious of Ukraine, he would have faced some opposition in the State Department, Pentagon, and other policymaking offices of the executive branch. If that opposition had risen to the level of outright insubordination or sabotage against the president, lots of people (myself included) would have sided with Trump, at least in principle. The duly elected president should be able to change the direction of foreign policy, especially when he campaigned on it. Members of "permanent Washington" such as Taylor and Kent are, as Trump likes to say, "unelected bureaucrats," and their views (however rooted in deep experience and long-standing relationships) can't be allowed to override the agenda of the president.

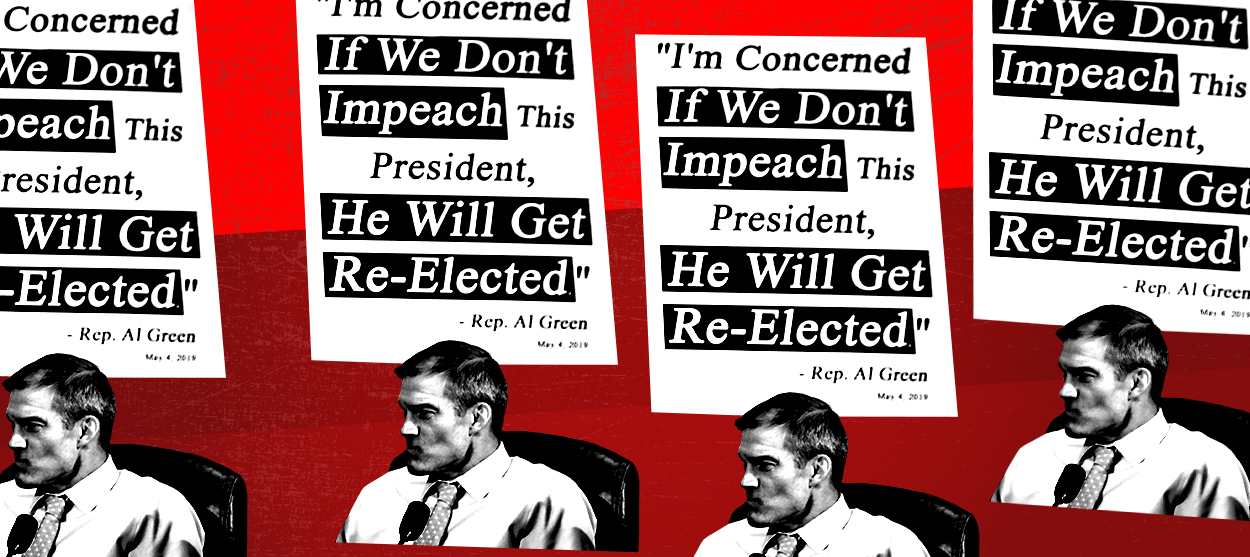

But this isn't what the impeachment inquiry is about. Trump is being impeached for attempting to use extortion to get a foreign government to intervene in an American election on his behalf. That is what Republican efforts to discredit the impeachment process and motives of witnesses who corroborate this charge are all about.

Those who believe there is nothing higher than political self-interest and the will to power need to face its implications. It can mean, and in this case does mean, defending acts that in ordinary, commonsense, non-cynical terms would be recognized as criminal and even potentially tyrannical. If Republicans flinch before this fact, even a little and even only in private, then they inadvertently provide evidence that deep down they continue to suspect there is something higher than political expediency — and that they know they are transgressing it in their efforts to let the head of their party transgress it, too.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred