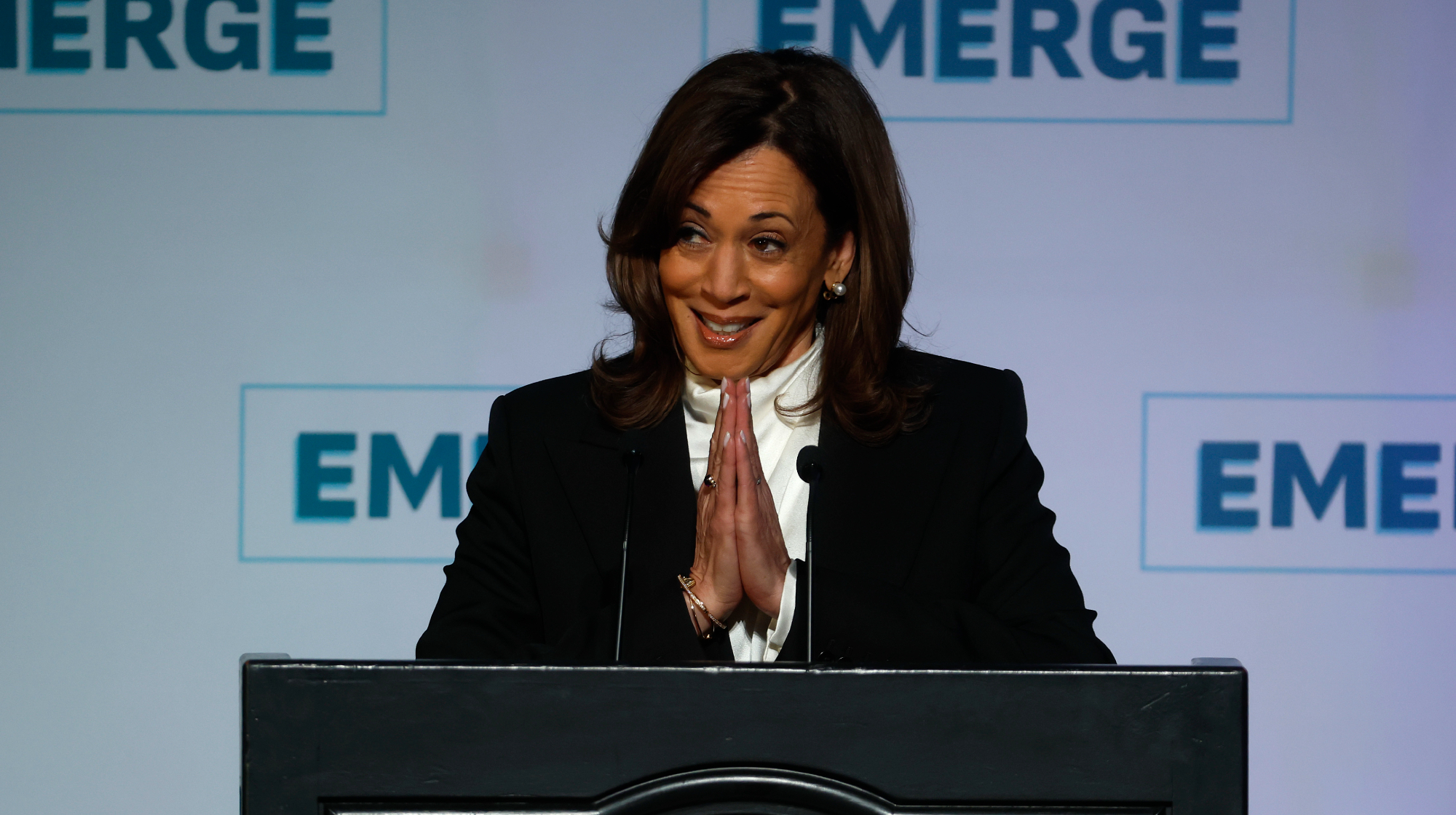

Why Kamala Harris failed

She was the perfect candidate — until she wasn't

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Kamala Harris was the perfect presidential candidate for the institutional Democratic Party in 2019. By which I mean that she talked, looked, and acted like she was grown in a top-secret high-tech lab deep in the bowls of the Democratic National Committee.

She was the total package. Smart, articulate, sassy, attractive, and as the child of immigrants from India and Jamaica, a seemingly flawless exemplar of 21st-century multicultural America. Her resume was equally stunning. A graduate of Howard University and the Hastings College of Law in the University of California system, she had elite credentials without seeming too elite. Her law career was spent in the public sector prosecuting criminals — first for the office of the San Francisco District Attorney, then as the DA herself, and finally as Attorney General for the state of California, before finally winning the Senate seat vacated by a retiring Barbara Boxer in 2016. A tough-as-nails, law-and-order black woman to take down President Trump: What could be better than that?

To judge by her decision on Tuesday to suspend her presidential campaign, plenty of Democrats thought lots of options were better. And therein lies a potent lesson for the Very Smart People in the Democratic Party establishment who were sure she'd catch fire.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Harris' campaign launch last January showed promise and generated all the excitement so many expected. Out of the gate, her polling average surged from 6.7 percent up to around 12 percent a month later. One year out from the first caucuses and primaries, that was more than respectable. Sure, Joe Biden (at 28 percent) and Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders (at 20) were ahead of her, but she was a solid third against two men who were much better known — a former vice president and the guy who gave Hillary Clinton a run for her money the last time around. Not bad at all.

Then came a slow deflation through the spring and into the summer, as Biden launched his campaign, skyrocketing up to a polling high of 41 percent in late May, and several other competitors jumped in, taking a point or two from each of the others until Harris was back down to 7 percent (and nearly 6 points behind a slowly rising Sen. Elizabeth Warren) on the eve of the first debate in late June.

That's when Harris got what turned out to be her one big break. In an exchange replayed and analyzed countless times in the days following the debate, the junior senator from California laid into Biden's record of opposing school busing as a means of rectifying racial segregation in the 1970s. She did it with consummate skill, personalizing the point by noting that she had benefitted from busing as a child growing up in the Bay Area. She left Biden in a puddle, confused and defensive.

People responded to what they saw and heard. In less than a week, Harris had more than doubled her standing, up to 15.2 percent. It was the highest she'd ever reach. A month later she drifted back down to 10 percent. By early September she was back to 7. A month later she'd fallen to 5, and she never rose much higher than that again. On the day she suspended her campaign, she stood at 3.4 percent. She blamed her decision on fundraising woes, which allowed liberal admirers to point fingers at overly cautious and racially blinkered donors. But the reality is that when you're mounting a national campaign for president just two months out from the Iowa caucuses, running a distant sixth place just isn't good enough to keep the lights on, no matter the candidate's race.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What happened? Harris tripped over her own two feet trying to dance to the clashing beats of the Democratic Party's many restive factions. Trying to appeal to all of them, she ended up appealing to hardly any.

Harris could have run as a proud prosecutor out to throw criminals in jail and enforce norms of law-abidingness, making her an ideal spokesperson to take on Trump's lawlessness. And she did exactly this. Sometimes. But at other times, she seemed ashamed of her own tough record as DA and AG, preferring not to talk about it or to talk around her reputation for harshness.

She did the same thing during the times in her campaign when she shifted gears and tried to run as an economic populist competing directly against Sanders and Warren. It was probably a desire to throw them off their game and make a play for their voters that led her to (at least sound like she intended to) endorse Medicare-for-all, including the abolition of private insurance. But it was probably a fear of alienating more centrist and older voters that led her to back away from those statements and release a health-care plan that included a role for private insurance. What inspired her to flip back and forth between these contradictory positions several more times is anyone's guess.

She even got tripped up about busing, making a point a few days later after her confrontation with Biden of clarifying that she didn't favor federally mandated busing — which was pretty much Biden's exact position on the issue back in the 1970s. No doubt advisers or donors (or both) had let her know that reviving the issue of busing — a major contributor to the rise of the so-called Reagan Democrats who helped to shift the American political spectrum to the right four decades ago — could (still) be radioactive to the party in 2020.

But if raising the issue of busing was a liability, why did she benefit from it in the polls? Maybe because the overly broad Democratic electoral coalition includes some people who still passionately favor federally mandated busing. But I think it's more likely that, for once, Harris sounded like she was speaking from the heart instead of following the directive of a political consultant.

Which brings us to what may well have been Harris's greatest liability of all — the phoniness factor. You've heard the old witticism: "The secret to success is sincerity. If you can fake that, you've got it made." That's true in many fields but in none more so than small-d democratic politics. Some people have the touch, but many — most — don't. At least this time around, Harris — with her flip-flops and manic run of smiles and laughs and claps and dance moves and oh-so-authentic tweeted Mother's Day cooking marathons complete with unironed freshly purchased aprons — didn't have it at all. She nearly always looked and sounded processed, synthetic, prone to overthinking, and engineered by committee.

Like her campaign itself.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame game

Democrats: Harris and Biden’s blame gameFeature Kamala Harris’ new memoir reveals frustrations over Biden’s reelection bid and her time as vice president

-

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’

‘We must empower young athletes with the knowledge to stay safe’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Harris rules out run for California governor

Harris rules out run for California governorSpeed Read The 2024 Democratic presidential nominee ended months of speculation about her plans for the contest

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein