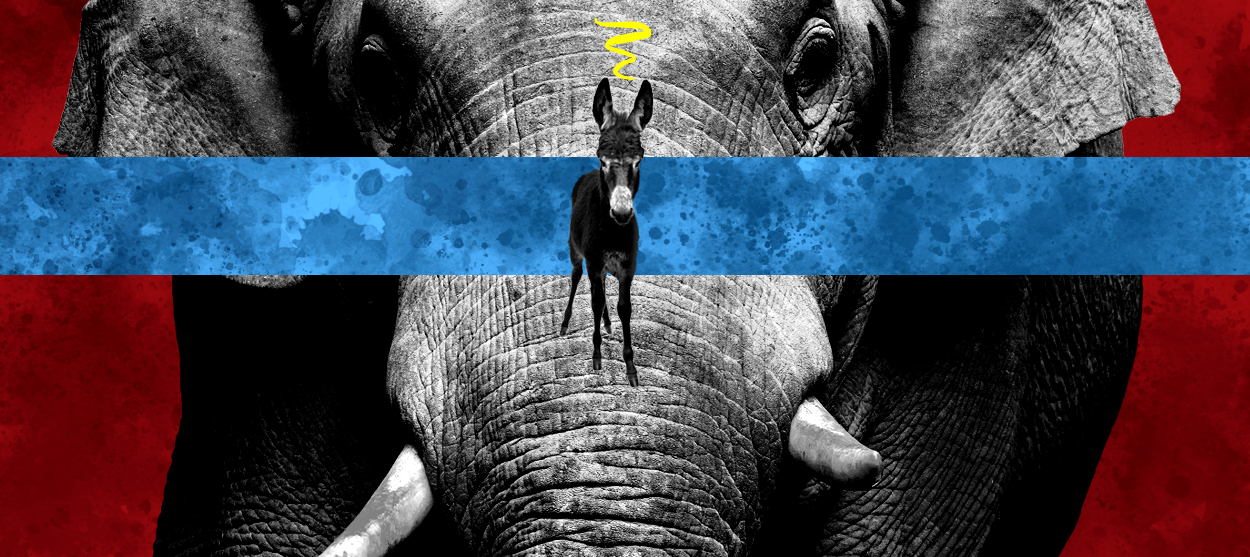

The GOP is ruthless

Can Democrats toughen up?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The last two days have given us an instructive glimpse of what American politics has become in the Trump era — and in particular of the stylistic and strategic gulf that now separates the country's two main parties.

On Monday, the Justice Department's Inspector General Michael Horowitz released his report on the use of surveillance powers by the FBI in the Russia investigation that ensnared the Trump campaign and administration. The report concluded that, although there were missteps in the investigation, the FBI displayed no bias in initiating the counter-intelligence probe. Democrats and anti-Trump conservatives praised the findings, calling them a vindication of federal law enforcement as well as a demonstration that the government can investigate itself fairly and rigorously.

Then, on Tuesday, House Democrats unveiled two articles of impeachment against President Trump, while also announcing that they had reached a deal with the administration for new provisions to strengthen the North American trade pact formerly known as NAFTA. Responding to critics who said it was ludicrous to give the president a policy win on the same day that articles of impeachment were presented to the country, Rep. Jim Himes (D-Conn.) responded that failing "for political gain" to do "something good for the American people" is "what the president is being impeached for," and Democrats were "not going to do that."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

On the other side of the aisle, things have been sharply different. Fastening onto the criticisms of the FBI in the IG report and blasting Horowitz for going much easier on the bureau than he should have, Trump has let loose with a barrage of invective against the entire process, including the judgment of FBI Director Christopher Wray, whom Trump himself appointed, for backing Horowitz. The president has been joined in the criticism by Attorney General William Barr, who sided with the president against Horowitz and the FBI he oversees.

When it comes to the articles of impeachment, Trump has blasted the process, promising to fight it every step of the way. He also spent a good part of the day meeting in the Oval Office with Sergey Lavrov, Russia's top diplomat — a man whose White House visit in 2017, coming one day after Trump fired FBI Director James Comey, sparked intense controversy after it was revealed that the president had disclosed highly classified information to him. When Lavrov's visit on Tuesday was over, Trump tweeted out a picture of himself with his guest along with a statement bragging about their "very good meeting." It was an astonishing gesture of contempt for his political opponents — almost a taunt on a day when they hoped to place him firmly on the defensive.

On one side, we have an earnest defense of process and extra-political institutions, and the public-spirited quest for bipartisanship in the name of the common good. On the other, a ruthless pursuit of political victory by any means necessary, including the generous use of disinformation, outright lies, and trolling. Put in slightly different terms, Republicans believe that the only way to achieve good things for the American people is to win as much political power as possible — to thoroughly vanquish their opponents, and to do so without mercy — while the Democrats … don't at all believe the same about themselves or their opponents.

Perhaps that goes a little too far. Some Democrats might believe it. But many don't. That certainly includes the Democratic presidential frontrunner, Joe Biden, who told a crowd in Iowa last week that he's "really worried" about either party having too much power. Though Trump's defeat would bring "serious consequences" for the GOP, Biden wanted Democratic voters to know that they shouldn't pine for a country without a Republican Party. "If you hear people on the rope line saying, 'I'm a Republican,' I say, 'Stay a Republican.' Vote for me but stay a Republican, because we need a Republican Party."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Is it even remotely conceivable that Trump or Barr or Rep. Devin Nunes of California or Rep. Matt Gaetz of Florida or any other prominent Republican member of the House would express such a high-minded, politically self-abnegating sentiment about the GOP? Or offer words of praise for the Democratic Party? Of course not.

And therein lies the greatest difference between the two parties as we prepare to enter the 2020 presidential race. It's not a difference over tax rates or the size of government or America's conduct in the world. It's a difference over how politics itself ought to be conducted.

The Democrats have a very broad — perhaps too broad — electoral coalition. It includes Bernie Sanders voters and Michael Bloomberg voters and even a few Tulsi Gabbard voters, and a whole lot of people between them. That's a massive ideological spread. And the act of trying to make the tent broad enough leads the party to include a fair number of Democrats who like Republicans more than they like many of their fellow Democrats. As a result, the Democratic Party is less a unified, goal-directed tribe than a ragtag coalition of ideological impulses and factional interests that sometimes agree about goals and tactics but often don't.

The GOP, by contrast, is a tribe in the relevant sense. Aside from a handful of conservative journalists, intellectuals, think tank analysts, and professors, who share the Democratic fondness for bipartisan consensus and deal-making across the aisle, and who define the common good in terms of the overcoming of partisanship, rank-and-file Republicans want their party to win above all else. They don't want to appoint a few conservative judges who will fight to a draw with liberal judges. They want to replace as many liberal judges as they possibly can with conservative judges so that conservative jurisprudence will prevail throughout the country. Republicans don't want to reach a compromise with liberalism or socialism. They want to rout liberalism and socialism. And for the most part, they are willing to suppress their differences in order to make it happen.

That's how we've ended up in a situation where Republicans come to the political battlefield brandishing pistols and Bowie knives, while Democrats show up armed with policy position papers and noble-sounding speeches.

As a writer who cares about ideas and public policy debates, and as an American whose soul is stirred by elevated political rhetoric, I know which side I prefer. But I also know which side is likely to prevail in a firefight.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred