Why impeachment favors the partisans

Impeachment is supremely political. Democrats would be wise to remember it.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Among the many strange quirks of American politics is the tendency of political actors engaged in political acts to claim they're not behaving politically. Most astonishing, politicians even express such expectations in the midst of undertaking one of our system's most supremely political acts: the impeachment and attempted removal from office of the president of the United States.

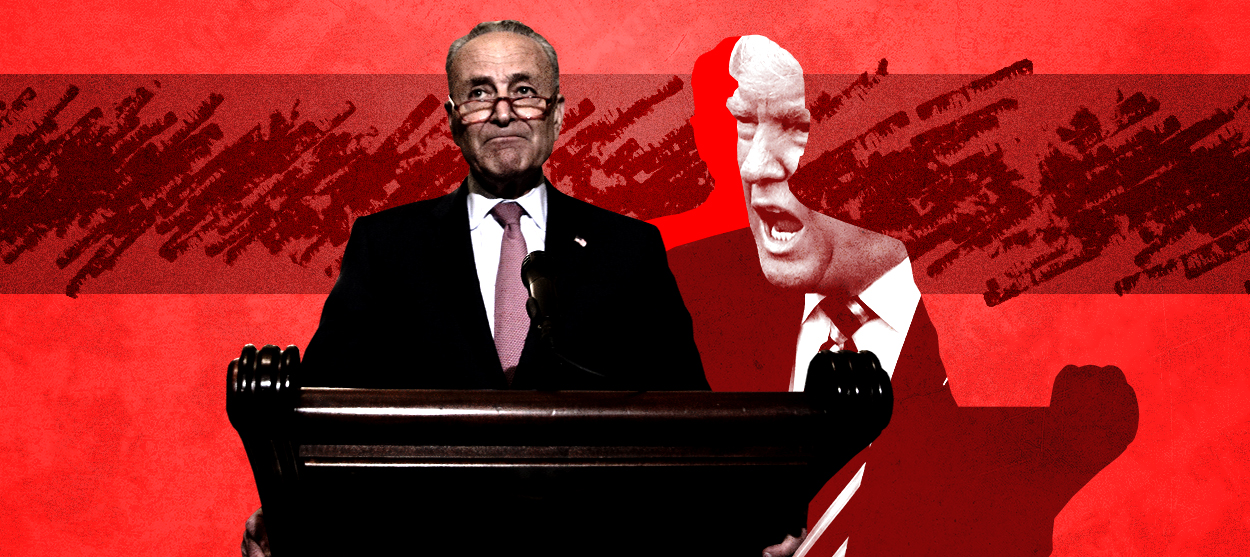

This tension — not to say contradiction — has marked every step in the impeachment of President Trump. Most recently, Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-N.Y.) released a public letter to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) in which he proposed a series of rules to govern the impeachment trial in the Senate. The trial, Schumer claimed, is an "enormously weighty and solemn responsibility" that must be viewed as "fair" and be conducted with "integrity and dignity." Hence the need for "a bipartisan spirit" to advance "shared objectives." If rules in that spirit come to be adopted, Schumer asserted, then the trial will demonstrate that "the Senate can put aside partisan concerns and fulfill its constitutional duty."

The invocation of such high-minded language is very American. Leaving aside its possible roots in aspects of American culture predating the founding period, the debates surrounding the adoption of the Constitution, as well as the words and deeds of our first president, bequeathed to the country an exalted mode of thinking about public life. The constitutional framers could certainly be hard-nosed about the need for lowered political expectations — for example, proposing checks and balances for a reality in which the virtue of public figures could never be assumed. But they also looked down on political parties and built a constitutional arrangement that presumed they wouldn't form (even as leading architects of the Constitution, such as James Madison and Thomas Jefferson, very quickly helped form them). In place of partisanship, the founders advocated public spiritedness that called forth sacrifice for the public good. George Washington's eight years in office was an exercise in enacting precisely such a noble politics.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Ever since, American politics has taken place in two modes. On the one hand, politicians have never shied away from the tough-minded, not to say cynical, pursuit of power. On the other hand, they regularly wrap that pursuit in regal gowns, as enacting an experiment in self-government, expressing the extra-partisan will of the American people, aiming at the overarching good of the nation, and growing out of a common-sense understanding of simple, self-evident truths affirmed by all people of good will.

In the best circumstances, thinking of politics in noble terms elevates public life in a way that benefits the country. (Just think of the beautiful turns of phrase, magnanimity, and wisdom contained in Washington's "Farewell Address" or Lincoln's "Second Inaugural.") But elevating politics too high can also breed a cynicism of its own, especially when appeals to the transcendence of politics are wedded to acts that obviously advance a partisan agenda. In such cases, Americans end up re-enacting a painful loss of innocence over and over again — starting out as naively admiring the seemingly public-spirited acts of politicians and then succumbing to anger and contempt when events reveal them to be motivated by the pursuit of lower or more partial goods.

That dynamic — swinging between high-minded rhetoric about politics and a scornful, distrustful dismissal of politicians — plays out every day in American public life, but it's become more fraught than usual in the highly polarized Trump era, especially in regular eruptions of what's come to be called "whataboutism." We've all seen it: Democrats adopt a pious, judgmental tone about Trump's defiance of an established presidential norm, and Republicans respond by asking, "what about when Barack Obama or Bill Clinton did something similar?" The gravity or severity of each example need not be even close to equivalent. All that's needed is for the same type of transgression to have been excused by the accusers in the past.

The reason this move is re-enacted so often is that the accuser's claim depends on him setting himself up as some kind of dispassionate, extra-partisan observer and rendering impartial judgment of the president's behavior. All the president and his fellow Republicans need to do to mount a defense is to demonstrate that the accuser is, in fact, not at all dispassionate, extra-partisan, or impartial. Once that has been done — once a charge of bias or double standards has been made — the accusation itself begins to seem less egregious. Suddenly setting oneself up as beyond politics comes to be seen as a supremely political act.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Which it is. Or at least can be — and certainly is in the case of impeachment. Members of the opposition party are attempting to remove the president from office. American civic habit and tradition, not to mention the solemn wording of the Constitution itself, will lead them to pretend they're acting above or outside of politics. But no one who isn't horribly naïve will be persuaded it's true. Impeachment is a political act that can only succeed when there is sufficient support in public opinion to support the act. The decision to portray the effort as above politics is one tactic designed to bring about that political end.

Note how much less fraught, less entangled in performative contradictions, it is to remove a prime minister in a parliamentary system. When parliamentarians take a vote of "no confidence," they don't put on airs about rendering objective judgment of the prime minister's failings, like some non-partisan judge appointed by God. They make a political decision about whether the government has lost sufficient public support to justify calling new elections. That's all.

It would be supremely un-American to proceed in this way — but it would also be wiser than the costume drama of a supposedly dispassionate, extra-political trial of Donald Trump in the well of the Senate.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred