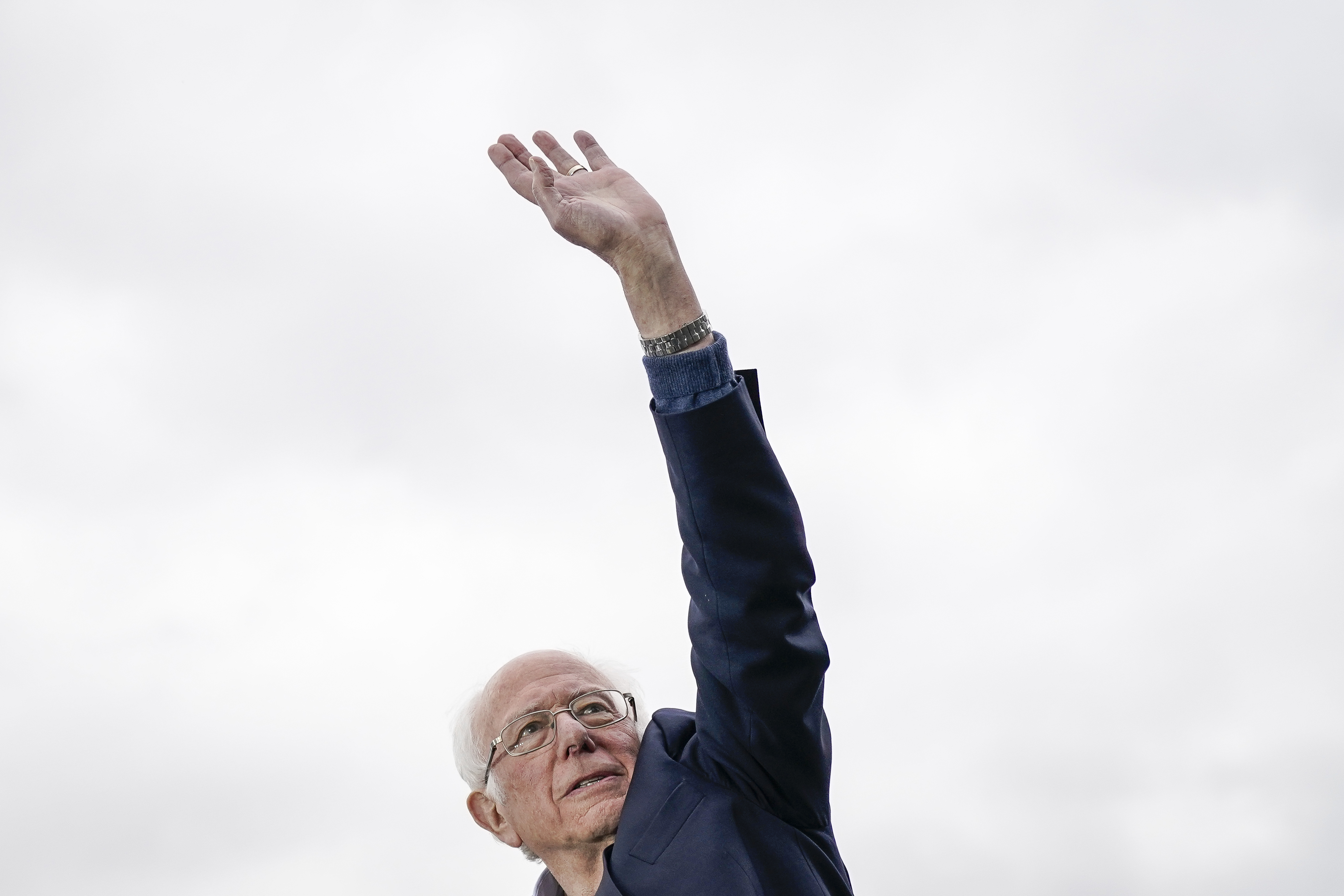

Don't panic about Bernie

What elections of the past can tell us about Sanders' frontrunner status

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

That sound you heard over the weekend was thousands of centrist pundits crying out in panic as it became apparent Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) stands a real chance of becoming the Democratic nominee for president.

"There is no sugarcoating the results," The Washington Post's Ruth Marcus grumped Sunday after Sanders won the Nevada caucuses in impressive fashion.

"In 30-plus years of politics, I've never seen this level of doom," Third Way's Matt Bennett told Politico.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

And on MSNBC, Chris Matthews — somewhat hysterically — likened Sanders' victory the Nazi defeat of the French army in 1940. "It's over," he pronounced.

Actually, it's not over. Yes, Sanders' accomplishments so far are impressive. But the Super Tuesday contests loom next week, when 14 states will cast their ballots then. That's a lot of voters, and a lot of convention delegates, who will be making their preferences known all at once. Sanders might emerge from Super Tuesday with an even larger lead over his rivals — but he might not. It will, however, definitely be easier to assess the state of the Democratic race after nearly a third of the nation has a chance to weigh in on the potential nominee.

That said, a look back at some recent presidential elections can give us context for Sanders' achievements thus far.

It's not 1992 anymore: For most of the past 50 years, Democratic presidential politics have been driven by fear of nominating a candidate too far to the left of the electorate. Richard Nixon blew out George McGovern in 1972; Ronald Reagan destroyed Walter Mondale in 1984. A whole generation of Democratic leaders — Bill Clinton foremost among them — learned to tack to the middle. Yes, Clinton pursued universal health care after winning in 1992, but he was also tough on crime and an unabashed capitalist, closing the deal on NAFTA and signing the repeal of Glass-Steagall legislation that had heavily regulated banks since the 1930s.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sanders' success, of course, defies that Clintonian logic. Naturally. There is a whole generation of 30-something voters who weren't even born when Michael Dukakis took his infamous tank ride in 1988. The Democratic losses those voters remember — Al Gore Jr. in 2000, Hillary Clinton in 2016 — seemed to have more to do with the esoteric nature of the Electoral College system than with any ideological extremism. They simply don't have the muscle memory to fear losing an election because the Democratic candidate veered too far left.

It's not 2000 anymore, either: By the turn of the century, the consensus of both the Republican and Democratic parties was so centrist that voters complained they couldn't really tell a meaningful difference between Al Gore Jr. and George W. Bush. Both were sons of power and privilege — Gore's dad was a senator; Bush's was the previous Republican president — and most meaningful questions of the election seemed to boil down to style: Was Gore's suit "alpha" enough? Could you get a beer with Bush? Voters further from the ideological center turned to Ralph Nader on the left and Pat Buchanan on the right for alternatives. Bush then spent eight years proving less moderate than advertised.

The election of 2020 is shaping up as an inversion of the Gore-Bush contest. The differences in a potential election campaign between Sanders and President Trump couldn't be starker. Sure, both are septuagenarian New Yorkers. But Trump runs on a record of tax cuts for the rich while Sanders wants to offer a range of new and expanded government services for poor and working class Americans. This year, it's the centrists who increasingly find themselves on the outside looking in.

But maybe it is still 2016, a little bit. Trump's victory over Hillary Clinton — while it comes with an Electoral College asterisk — surprised the establishment, and set off a search for answers that still hasn't quite abated. Many on the left chalked the result up to sheer racism, a backlash from white America against eight years of governance by a black man.

It's a fair theory, but the rise of a lefty populist movement to support Sanders suggests that story is incomplete. Sanders' voters see a world where education, housing, and health care are increasingly unaffordable. They fear losing ground in their own lives and the lives of their loved ones — and are voting accordingly.

Sanders could still lose momentum. But after his strong showing against Hillary Clinton in 2016 and his powerful start to the 2020 race, it is probably time for activists and observers to stop panicking at the prospect of his success and figure out how that can help them better serve a restless public.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Joel Mathis is a writer with 30 years of newspaper and online journalism experience. His work also regularly appears in National Geographic and The Kansas City Star. His awards include best online commentary at the Online News Association and (twice) at the City and Regional Magazine Association.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Mamdani vows big changes as New York’s new mayor

Mamdani vows big changes as New York’s new mayorSpeed Read

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The anger fueling the Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez barnstorming tour

The anger fueling the Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez barnstorming tourTalking Points The duo is drawing big anti-Trump crowds in red states