Pandemic, but make it fashion

The cultural response to coronavirus is a modern twist on a retro classic

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The history of fashion is a history, also, of disease. Italian survivors of the Black Death, newly rich off wealth inherited from relatives who weren't quite so lucky, pushed medieval clothing trends to become more elaborate in style and design. In the 1800s, when "consumptive chic" was all the rage, women's clothing emphasized the willowy waists of wannabe tuberculosis sufferers; later, when having TB fell out of favor, the disease wiped out the trend of long Victorian skirts, the fear being that trains might sweep up germs in their folds. And when the AIDS crisis struck, male designers suffered a blow from the resulting homophobia and "the fear that nobody would want to buy a blouse or underwear because it came from a designer who, in the mind of mass America, probably stitched each of those garments with his own diseased hand," as one publicist told the Philadelphia Inquirer in 1986.

Now, with coronavirus threatening to become a global pandemic, the clothing and wellness industries are once again being shaped by the miasmas of paranoia, misinformation, and modern-day influencers. Websites from British Vogue to Tatler have published articles in recent weeks with tips on how to "avoid freaking out about the coronavirus" or how to "get apocalypse-ready with inspiration straight from the runway." On the one hand, the fashion industry's opportunism is just capitalism — a health crisis threatening billions of lives is another chance to make a buck. On the other hand, it's a reminder of what's been proven over centuries: that we've long sought comfort in snake oil, especially when it makes us look good.

Last Sunday, iconic fashion designer Giorgio Armani announced that his Milan Fashion Week show would be live-streamed, rather than presented before a live audience, in order to "safeguard the well-being of all his invited guests by not having them attend crowded spaces." It wasn't an overreaction; Italy is in the throes of a coronavirus outbreak, having shut down schools and quarantined a number of towns. Armani himself was photographed donning a mask to attend his show, although based on pictures, he wore a simple surgical mask that would have done nothing to protect against the virus, were he actually exposed to it. Still, the proliferation of masks on the fringes of the runway — often the wrong kind to even prevent contraction — are evidence that 21st-century "pandemic chic" still has more to do with appearance than real practicality.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

"Flu masks," as they're commonly called, first became widely popular during the 1918 Spanish Influenza, especially in Japan, where the culture never truly faded. But health experts have warned that wearing a mask likely does little protect you from the virus (although it's a helpful thing to wear if you already have it). Surgical masks "are not tight enough to prevent what's already in the air from getting in," and the more specialized N95 masks, which could potentially offer protection, are often improperly fitted or worn incorrectly by anxious customers, The Washington Post reports. "If you just buy them at CVS … you're not going to get it fit-tested, and you're not going to be wearing it properly, so all you've done is spend a lot of money on a very fancy face mask," Timothy Brewer, a professor of epidemiology and medicine at UCLA's Fielding School of Public Health, added to the Post. Maybe that's the point: Ultimately, "coronavirus influencers" are peddling a fad, and not necessarily one that does much to keep you healthy.

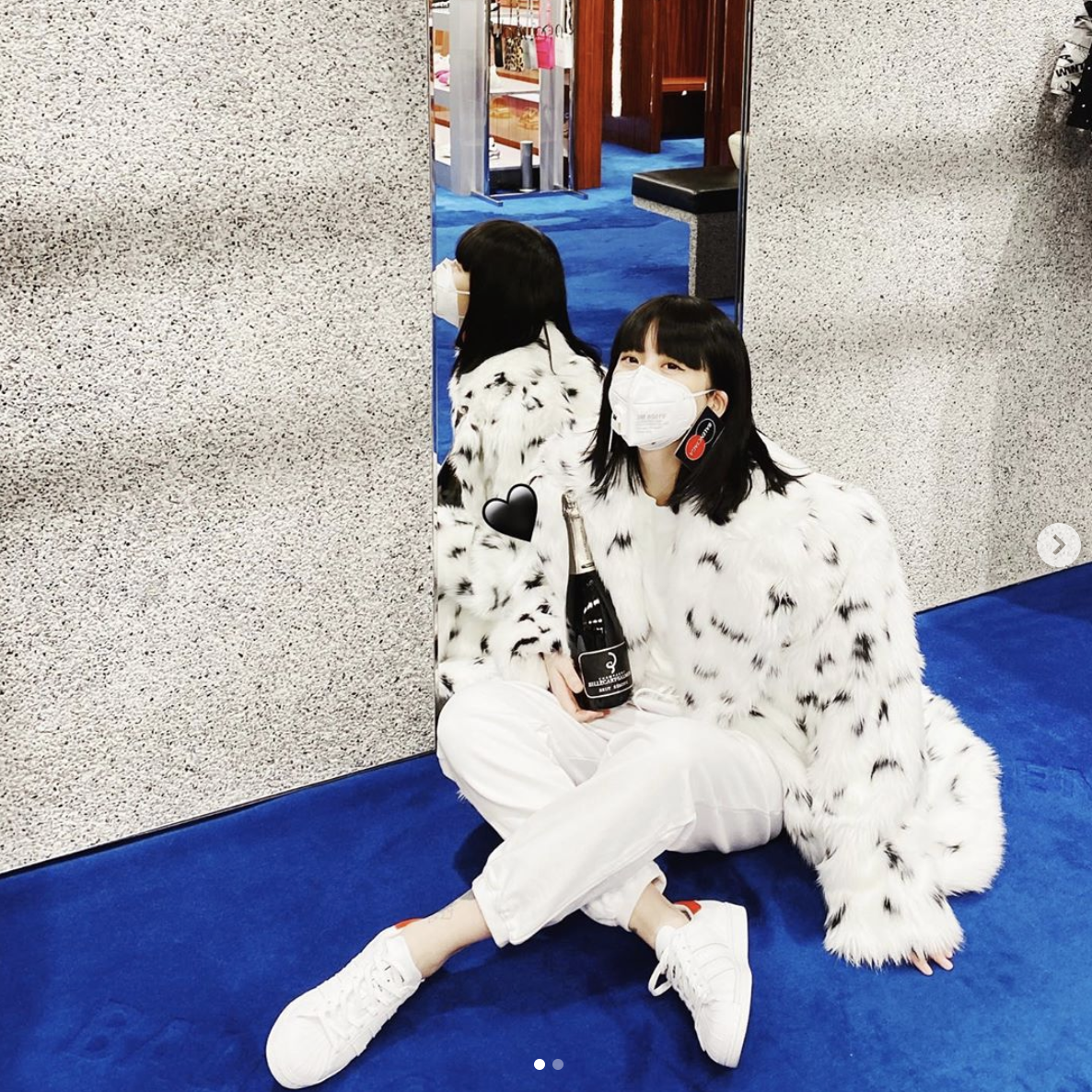

Still, that hasn't stopped the media from jumping in on attempting to make coronavirus attire the next Silly Bandz. "Here are five masks we would actually wear," recently wrote Sunset in an article that promoted "actually-maybe-kinda-cute flu masks" with "groovy" and "silly gnashing teeth" designs. A number of influencers and celebrities have donned masks to pose for photos; Bella Hadid shared a video of herself leaving Italy in one. And demand, correspondingly, is through the roof; a mask manufacturer in China told Reuters that "clients are demanding a combined 200 million masks per day compared to its normal production rate of 400,000 a day." While masks might not be particularly useful for anything other than snapping a selfie — and at worse, are luring wearers into a false sense of security — as Tatler observed, they at least "won't jeopardize your style."

And masks might only be the beginning. Coronavirus could potentially even begin to shape facial hair trends after the CDC published a warning on Wednesday that certain styles make wearing masks less effective. British Vogue also recently published "tips to help you keep calm and carry on" during the outbreak, including purchasing a "luxury hand wash," using essential oils, and visiting a "light salon," none of which actually make any sense for protecting you from a novel virus. In an attempt to get in front of such opportunism, the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health has even had to emphasize that "purported remedies [for coronavirus] include herbal therapies and teas" but "there is no scientific evidence that any of these alternative remedies can prevent or cure the illness caused by this virus."

Even so, there is something of an I was there appeal to snapping a selfie in a coronavirus mask. If centuries of history can tell us anything, after all, it's that a good trend is as contagious as any pathogen. While there is something especially modern about the way the coronavirus marketplace is developing — on livestreams and influencers' Instagrams — the impulse itself is timeless.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Sure, we've come a long way from the macabre beaked masks of plague doctors, but pandemic chic never goes out of style.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeva Lange was the executive editor at TheWeek.com. She formerly served as The Week's deputy editor and culture critic. She is also a contributor to Screen Slate, and her writing has appeared in The New York Daily News, The Awl, Vice, and Gothamist, among other publications. Jeva lives in New York City. Follow her on Twitter.