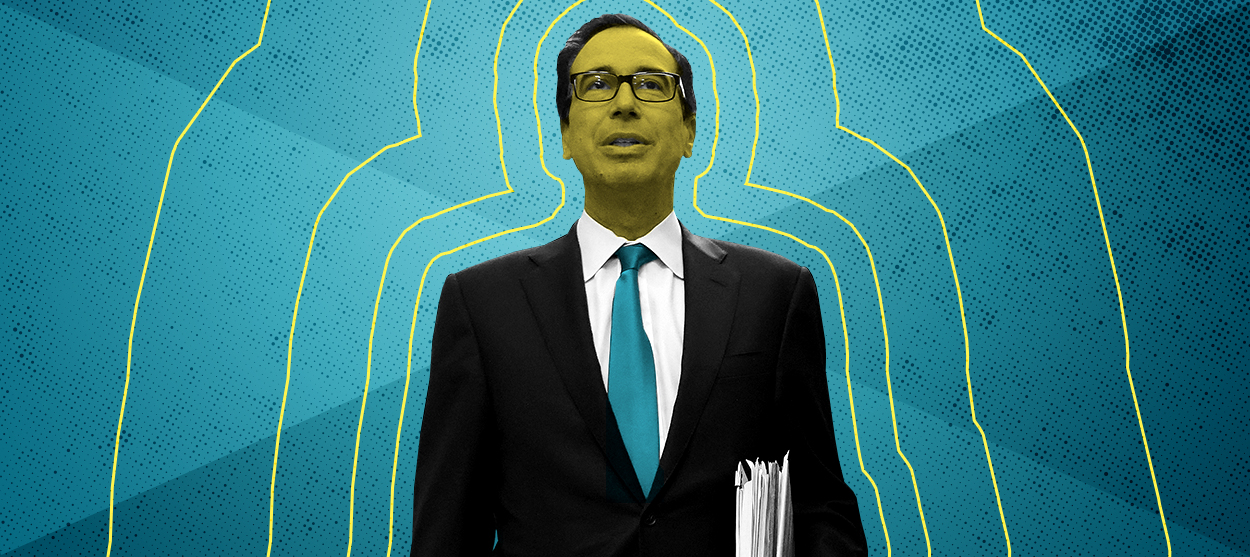

Steve Mnuchin is right about airline bailouts

His terms are a pretty good test of whether the companies actually need the money

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

The Treasury Department and a number of major airlines closed a deal Tuesday evening to get the industry in on the $2.2 trillion Congress is spending to fight the coronavirus pandemic. The CARES Act set aside about $58 billion to help airlines and their contractors specifically, and that money was supposed to start moving over a week ago. But the airlines and Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin got into a scuffle over the terms the companies will have to abide by.

The Trump administration has a reputation for being extremely amenable to big business. But in this case, Mnuchin got cross-ways with some Democratic lawmakers, airline unions, and other groups that actually wanted him to ease up. And to his credit, one of Mnuchin's demands in particular — that recipients of aid give the government some company shares in exchange — is actually a pretty good test of whether the airlines actually need the money.

The $58 billion pot is divided into three parts: There's $25 billion in loans and loan guarantees to help the passenger airlines, another $25 billion in direct aid to help the airlines keep workers on payroll and continue providing them benefits, and then the other $8 billion is to help cargo airlines and industry contractors. All of which is meant to tide the airline industry over until the end of September.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The controversy concerned that second $25 billion slice: the one that's supposed to support worker pay. The CARES Act language gives Mnuchin some leeway in setting terms, and he demand two key things: First, that 30 percent of that money won't actually be one-way cash grant; they'll be low-interest loans that have to be paid back over several years. Second, that the government get stock in the airlines equal to 10 percent of those loans. (These conditions would not apply to smaller airlines getting less than $100 million from the government.)

There were other conditions as well: the big airlines have to maintain a certain level of service around the country, they have to limit executive compensation, they can't pay out dividends or do stock buybacks for a certain period, and of course they can't lay off workers or cut salaries. But those requirements seemed to be relatively uncontroversial. It was the first two asks that ruffled everyone's feathers. Earlier this month, Boeing CEO David Calhoun more or less told Fox Business the government's demand for equity was a deal-breaker: "If they force it, we just look at all the other options, and we've got plenty of them," he said.

Details on the final deal are still coming in, but it looks like Mnuchin came pretty close to getting everything he wanted. Delta Airlines, to take one example, will get $5.4 billion, of which $1.6 billion will be low-interest loans due over 10 years, and it will hand over 1 percent of its shares to the government. Reporting did not include Boeing as one of the companies participating in the deal, so it looks like Calhoun did indeed wind up looking elsewhere.

Interestingly, the airlines' initial opposition to handing over stock got support from some unexpected quarters in Congress. Democratic Party leadership in the Houser wrote a letter to Mnuchin saying that, while they understood what he was trying to do, he should get the aid out as quickly as possible and with minimal fuss, since it's meant to keep workers on payroll. "Assistance must not come with unreasonable conditions that would force an employer to choose bankruptcy instead of providing payroll grants to its workers," they wrote.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The airline industry's labor unions were also upset about Mnuchin's demands. Though in their case, the complaint was more with the 30 percent of the $25 billion that Mnuchin wanted paid back as loans. And on that specific issue, the Treasury Secretary's critics had a point: Structuring some of the aid as a loan will saddle the airlines with debt repayment obligations long after the economy has (presumably, hopefully) gotten back on its feet. That will make the airlines at least somewhat less financially stable than they otherwise would be, which is a threat to the businesses and their workers alike.

But demanding shares from the airlines is another matter. That has no impact on the health of the airlines' finances at all. In fact, the way for the industry to maximize its long-term financial stability would be to not pay any dividends or do any buybacks for any shares whatsoever, government-owned or otherwise.

Now, it's always worth remembering that the federal government doesn't need the money these shares would pay out. It's the creator of U.S. dollars, after all. Thus, Mnuchin's own exhortation that American taxpayers should be "compensated" for the money doesn't make a whole lot of sense. The CARES Act also made clear that any equity stakes the government takes can't be voting shares, so it's not going to be interfering in corporate governance. (Whether the government should interfere is a question for another day.) But as the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute (EPI) pointed out, demanding shares is a good test of whether a company actually needs the help. "By granting the government equity, these companies would dilute existing shareholders' claims on future profits," EPI wrote. "If these existing shareholders are unwilling to allow this dilution, this is a clear sign that they firmly expect the company to continue operations even without a bailout."

Contra House Democratic leadership, telling the airlines ownership class that they can either take a haircut on profits or go without government aid is hardly "forcing" them into bankruptcy. Characterizing it that way is a tacit admission that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Cali.) and top Democrats see no way to help regular Americans that doesn't intrinsically involve bribing the wealthy. And the 1 percent of shares Delta is giving up, for instance, is hardly a major dilution of private investors ownership stakes. As EPI noted, Boeing's Calhoun straight up said the company has "other options" if they don't like the government's terms. "If there are other ways to cope, then a bailout is, by definition, not needed," EPI concluded.

Admittedly, neither the Federal Reserve's loan offer to big businesses, nor the Treasury Department's loan program for small businesses (most of which will ultimately be forgiven), are demanding company shares in exchange, though they will ultimately provide hundreds of billions, if not trillions, in aid. But those are also sweeping programs meant to encompass the entire economy, and offer help to all comers. They are not aimed at helping one specific industry. If there was an element of capriciousness to Mnuchin's demands, he was also reportedly determined to make sure this program doesn't garner the same hated reputation as the bank bailouts that followed 2008's Great Recession. Which is hardly a crazy goal.

No company can or should be expected to plan ahead for a crisis like the coronavirus pandemic. But the fact remains that when the government hands out aid in circumstances like this, it is inescapably handing out future market power. When that giveaway of power is directed at a specific group of companies, it's understandable to demand assurances that the need for it is truly existential.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Jeff Spross was the economics and business correspondent at TheWeek.com. He was previously a reporter at ThinkProgress.

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

Movies to watch in February

Movies to watch in Februarythe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance iceberg

ICE’s facial scanning is the tip of the surveillance icebergIN THE SPOTLIGHT Federal troops are increasingly turning to high-tech tracking tools that push the boundaries of personal privacy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred