Will America embrace voting by mail?

If the coronavirus still poses a threat in November, should Americans be able to cast ballots from home?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If the coronavirus still poses a threat in November, should Americans be able to cast ballots from home? Here's everything you need to know:

What will happen in November?

No one knows yet. But if fear of infection continues to shape our daily lives through the fall — or if the virus dies down and returns in a second wave — the implications for November's presidential election will be dire. Not only will voters have to risk infection to go to the polls, potentially keeping many at home, but finding poll workers willing to deal with hundreds of voters could be a daunting obstacle. The recent primary in Wisconsin, in which shuttered polling places forced voters to risk infection while standing in long lines that conflicted with the state's stay-at-home order, offered a nightmare vision of what November could bring. Many believe mail-in voting is the answer.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How would mail-in voting work?

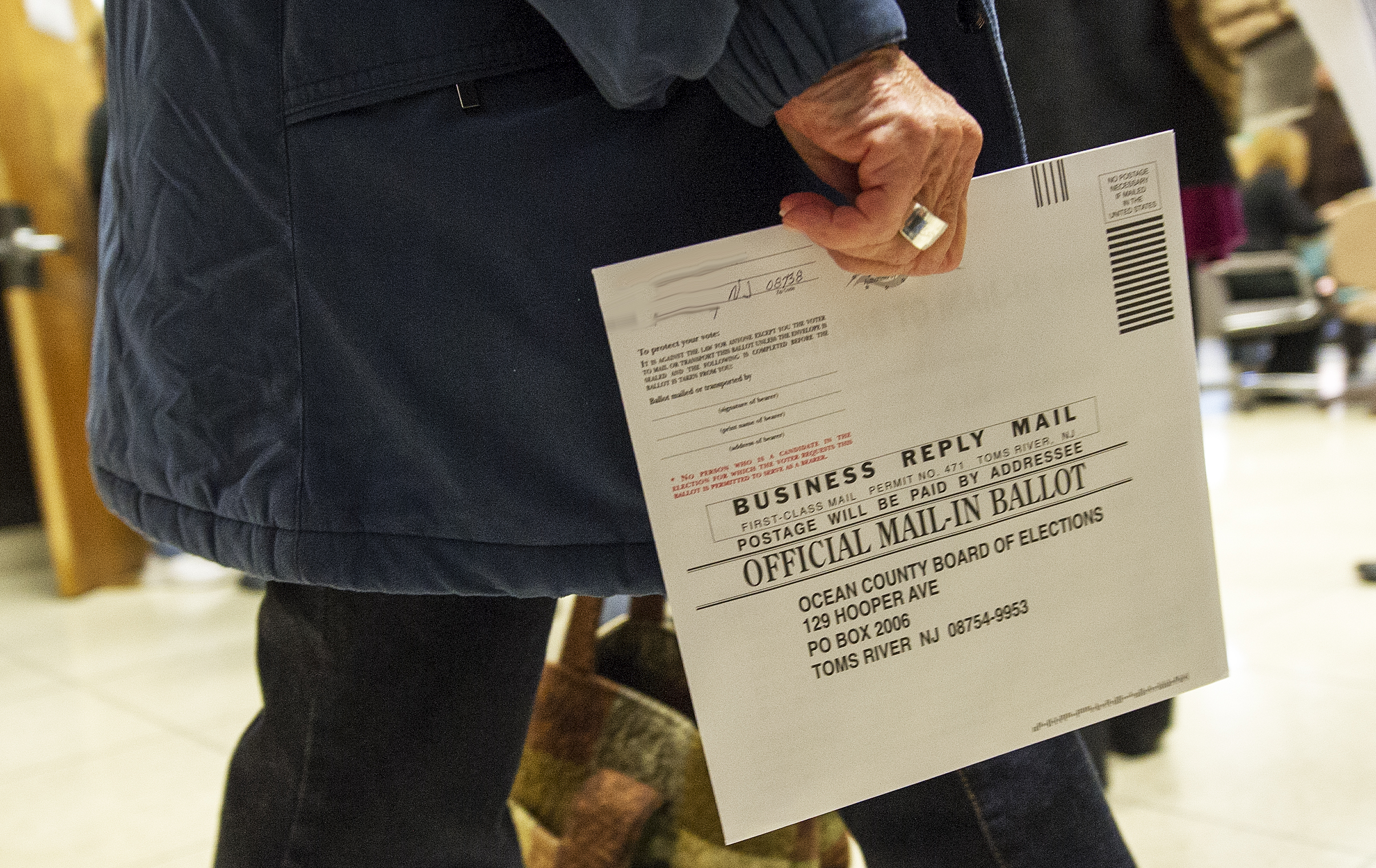

Five states — Washington, Hawaii, Oregon, Colorado, and Utah — already hold their elections almost exclusively by mail. In those states, registered voters are sent ballots, which they fill out, place in a secure, signed envelope, and can return by mail or bring to video-monitored drop boxes in libraries, fire stations, and other locales. A bar code verifies that it's a legitimate ballot mailed by the state, and signatures of voters can be checked against those on file. In these states, in-person voting remains available, generally on Election Day and during an early-voting period. Several other states have extensive mail balloting, and every state already allows mail-in voting under certain conditions, as with absentee ballots for military and overseas voters. In 2018, 26 percent of ballots nationwide were cast by mail.

Could mail-in go national?

Yes — but there are many obstacles. For starters, tens of millions of ballots and envelopes need to be designed and printed. States have to create systems to collect and count them, which involves buying scanners and training a workforce that will be needed over weeks instead of a single day. Outreach campaigns will have to educate voters. To be ready for November, these efforts need to start as soon as possible. "It's not something you can turn around overnight," said Patrick Gannon, spokesman for the North Carolina Board of Elections. It also won't be cheap. The national price tag could reach $2 billion, according to a report from the Brennan Center for Justice. On top of that, there are legal hurdles.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What are they?

Most states allow mail-in voting for anyone who requests a ballot. But a third of states require voters to provide a reason they can't show up in person (though some waive the rule for older voters). Altering those rules requires a change to state election laws. However, Congress has the power to overrule state laws and permit mail-in voting on a national scale. A bill introduced by Democratic Sens. Ron Wyden and Amy Klobuchar would require all states to offer on-demand mail balloting, along with early in-person voting, and earmarks $500 million to help pay for it. Democrats tried to make these provisions part of the recent stimulus bill and have vowed to try again with the next one. But they face opposition from Republican elected officials, though not most Republican voters.

Why is this a partisan issue?

Some, including Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.), say it's an issue of federalism; they object to Congress dictating state election terms. Others, like President Trump, say mail balloting opens the door to election tampering. "There's tremendous potential for voter fraud," said Trump, who exhorted Republicans to "fight very hard" against it. Research has shown that voter fraud of any kind is exceedingly rare, and there is no evidence of significant problems in the states that rely on mail-in ballots almost exclusively. But many Republicans believe that groups who lean Democratic — blacks, Hispanics, and young people — will vote in greater numbers if they can vote from home. Trump said increased turnout from mail-in voting leads to "levels of voting" that would mean "you'd never have a Republican elected in this country again."

Is that true?

Several studies of mail-in voting, including one by Stanford University released last week, have found that while it raises turnout by about 2 percent, it provides no Democratic advantage. In fact, it actually boosts voting percentages among rural and senior voters, who skew Republican. An analysis of the 2016 North Carolina election showed that Republicans were more likely to vote by mail than Democrats. Mail-in voting "might well deliver Republicans a net advantage," argues former Republican National Committee chair Michael Steele. A new poll shows bipartisan public support for mail balloting this year, with 65 percent of Republicans in favor. Still, many conservatives condemn mail-in voting in apocalyptic terms. "Universal vote by mail would be the end of our republic as we know it," said Rep. Thomas Massie (R-Ky.).

'Harvesting' people's votes

One of the more contentious issues around mail-in voting is a practice called "ballot harvesting." Nearly half of states allow someone other than the voter to collect and deliver ballots. Defenders of third-party delivery say it enables elderly, handicapped, and other homebound voters to return ballots, but opponents say activists use it to boost turnout for their party, opening the door to fraud. Ballot harvesting received wide attention in 2018, after Republicans charged that legal vote harvesting helped Democrats win upsets in California's Orange County. "People were carrying in stacks of 100 and 200 of them," said Neal Kelley, the county's registrar for voters. Last year, the results of a 2018 congressional election in North Carolina were thrown out after a Republican operative was charged with running a vote-harvesting operation in defiance of state law. The operative, Leslie McCrae Dowless, allegedly paid workers to collect ballots, including some blank ones that were subsequently filled out. Ballot harvesting, says Hans von Spakovsky of the conservative Heritage Foundation, enables campaign operatives to influence voters — or even tear up their ballots — without anyone watching. "There is no one present to ensure that voters are not being coerced, intimidated, threatened, or paid for their vote," von Spakovsky said.

This article was first published in the latest issue of The Week magazine. If you want to read more like it, you can try six risk-free issues of the magazine here.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred