An economic turning point for Europe?

The coronavirus may finally shock the continent out of its austerity mindset

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Most of the big eurozone countries were caught badly unawares by the coronavirus pandemic. France, Spain, Italy, and even Germany suffered severe outbreaks, though most are well on the way to being contained now.

Now eurozone countries are beginning to deal with the resulting economic fallout — and there are some surprising glimmerings of hope that they might actually fix the snarled economic institutions and austerity fixation that have throttled the region's economy since 2008. It is far from a sure thing, but it is the best opportunity in years, and a potential major turning point in the trajectory of the European Union.

Let me review some background. For over a decade the eurozone has been in the stranglehold of an austerity cult. After the initial economic crisis of 2008, the currency area fell into a debt crisis caused not by debt itself, but by the political strictures of the eurozone structure. As Steve Randy Waldman explains, a eurozone-wide crisis that clearly called for a region-wide response was instead pinned on a few scapegoats. Countries like Italy and Greece had indeed borrowed heavily during the preceding decade, but were encouraged to do so by banks in Northern Europe, especially France and Germany. Those same banks had also invested heavily in U.S. mortgage securities, which both turned out to be full of toxic waste, and more importantly, denominated in dollars. Where the U.S. could borrow and print dollars to its heart's content to rescue its banks, Western Europe (unlike China or Russia) had no big dollar hoards to defend itself. A severe dollar shortage quickly developed on the continent as banks tried to unwind their positions. By 2009, a euro-dollar currency crisis was looming, and thereafter a chaotic collapse of the European banking system.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Some kind of banking rescue was unavoidable, but simply saving the banks from their own misdeeds with no punishment or reckoning, out in the open, would have been deeply unpopular. So Eurozone elites chose to bail out the banks by routing the money through peripheral nations, especially Greece. That country got a "bailout" in 2010, but almost all the money went directly to French and German banks to get Greek loans off their books. Meanwhile, the Federal Reserve quietly forestalled a currency crisis by granting the European Central Bank (and several other nations) the power to exchange printed euros for dollars. Those two programs, which got little attention, allowed rich eurozone countries to save their banks.

Then, so euro elites could pretend they weren't just rescuing their idiot banker friends, and to maintain the fiction of neoliberal orthodoxy, they forced gallons of austerity poison down Greece's throat. The whole problem was blamed on purported Greek irresponsibility, which must be paid for with eyewatering tax hikes and savage cuts to social programs. This crushed the Greek economy, which shrank by 28 percent by 2015. Unemployment soared to almost 28 percent. That in turn made the debt problem worse, not better, as the Greek economy shrank faster than the debt load. It had still not come even close to recovery when the pandemic struck.

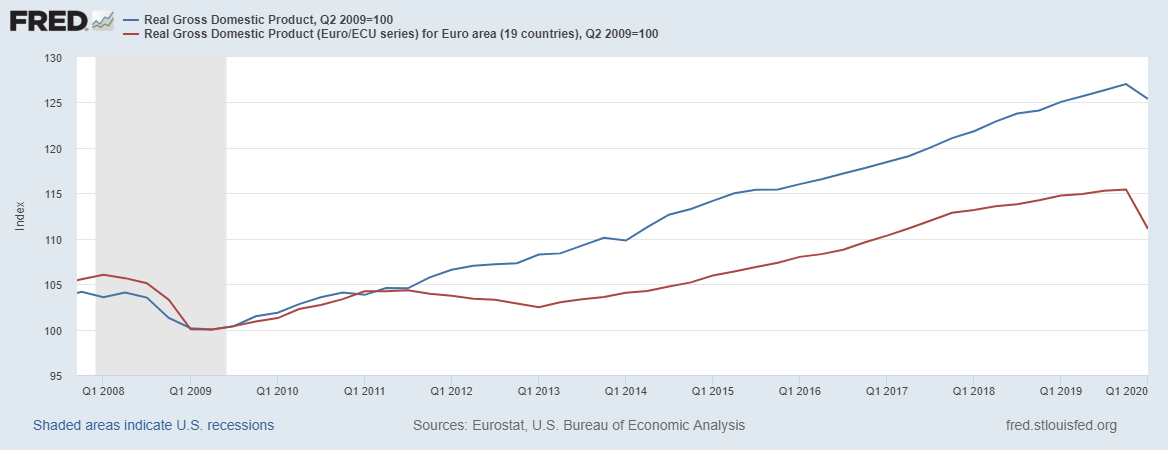

The broader economic consequences have been disastrous — the eurozone as a whole has been in a moderate depression for a decade, with countries like Germany and France doing only somewhat poorly but ones like Greece, Spain, and Italy suffering a 1930s-scale catastrophe. Here I have charted inflation-adjusted eurozone growth (in red) against that of the United States (in blue), showing the change since the second quarter of 2009 (scaled to 100). Up through the last quarter of 2019, the U.S. economy had grown by 27 percent, while the eurozone had grown by just 15 percent — a yearly average of a meager 0.98 percent over the period:

It's important to remember also that the U.S. growth record is itself lousy over this period, coming in at about 15 percent below the previous 1945-2007 trend. What the eurozone very obviously needed in 2009-10 was a write-off of unpayable debts (which additionally would have sent a signal to both nations and lenders to be more careful in future), a restructuring of its rotten banks, and a honking great stimulus package to restore employment and growth — perhaps funded by eurozone-wide bonds. With all that, the eurozone could have beaten the American sluggard easily, but instead it made everything worse, and hence fell well short of even that humiliating mark.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

However, the coronavirus pandemic seems to have broken, temporarily at least, the austerity mindset. Countries across the continent have been forced to spend huge sums to keep their economies in stasis during the lockdown. These programs have been funded by borrowing, and interest rates in the eurozone have been kept down by the European Central Bank — which, instead of causing a bank run to smash leftist governments, as it did in Greece in 2015, is actually buying up government debt across the currency area, as a central bank should do in a crisis. Remarkably, now the whole European Union — which includes 27 states, not just the 19 in the eurozone — is now considering a $2 trillion coronavirus relief package, funded by bonds backed by the entire EU. If approved (requiring a unanimous vote), the point would be to cushion the blow to the hardest-hit countries, allowing them to spend more without increasing their sovereign debt.

Now, the German Constitutional Court recently challenged a European Court of Justice ruling that the ECB bond-buying program is legal, throwing a possible legal wrench into its support of euro area debt markets. This raises the prospect that German conservatives, who have been the main political force behind austerity, will block coronavirus relief and reform. However, the grounds for the ruling were that the ECB was overstepping its legal authority, which is obviously true and has been for years. According to European treaties, the ECB is not supposed to intervene in politics, but it has been perhaps the most meddlesome political institution on the continent for the last decade — just now doing so in a beneficial way rather than acting as the thuggish leg-breaker for austerity.

A response to the German ruling could be a new treaty or legal settlement subjecting the ECB to democratic oversight. That, plus the creation of EU or eurozone bonds, could be the first step towards true economic democracy on the continent. Central bank "independence" is a ridiculous impossibility — all central banks are inherently political. If it was democratically-elected authorities overseeing the ECB's power, rather than finance-connected elites, the chance of that power being exercised for good, and the European population accepting those decisions as legitimate, would be greatly increased.

The European project stands at a crossroads. The whole point of the EU and the eurozone was to defuse the nationalist passions that touched off the worst war in history. A more connected Europe, it was argued, would be a less dangerous one. Instead, elite bungling and austerity have rekindled the flames of right-wing nationalism across the continent. Already the EU has lost one member state, and should it continue down the pre-crisis path of economic stagnation and authoritarian austerity, more would likely follow.

The pandemic is a chance to reverse that damage. It turns out Greece, which handled its outbreak far, far better even than Germany, has much to teach its neighbors. European citizens and policymakers may not get another chance to create a European economy that works for all Europeans. I suggest they seize it.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.

-

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?

Is Andrew’s arrest the end for the monarchy?The King has distanced the Royal Family from his disgraced brother but a ‘fit of revolutionary disgust’ could still wipe them out

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred