In the fight for justice, moderation is a virtue

Extremism is counterproductive

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Conservative Republican Barry Goldwater is famous for proclaiming from the stage of the 1964 GOP convention that "moderation in pursuit of justice is no virtue." But he was wrong. That was true when Goldwater spoke the words just a few weeks after voting against that year's landmark Civil Rights Act — and it's true today, when activists express similar views at Black Lives Matters protests and the sentiment reverberates through newsrooms, corporations, nonprofit organizations, and universities, where well-meaning people are trying to devise a response to justified and long-standing grievances.

Now as then, moderation in pursuit of justice is essential.

That truth can be hard for Americans to accept, and understandably so. After 250 years of slavery, 100 years of Jim Crow, decades of redlining and police brutality and mass incarceration, the call for moderation can sound like an expression of complacency and white privilege. I've written with outrage about racial injustice in this country, and about police abuse of power, and engaged deeply with arguments for reparations and for placing the ideology of white supremacy at the center of our understanding of American history. I support many of the same things the protesters do, especially justice for Black citizens (equal treatment under the law) and serious police reform.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

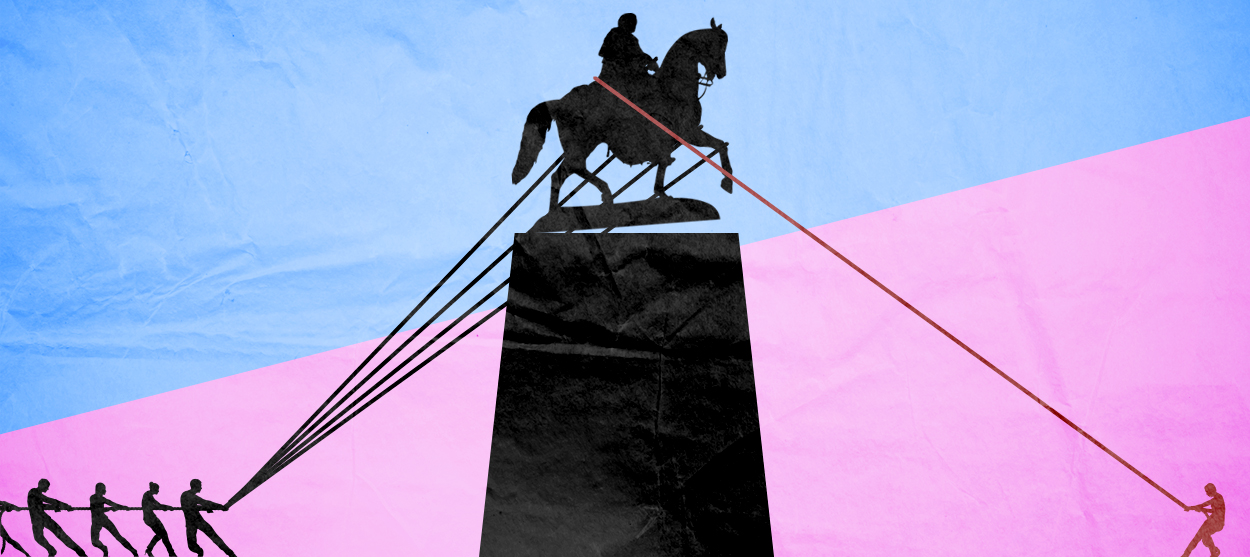

But what I don't support is a certain radical approach to pursuing these goals. I don't support petitions that seek to fire professors for failing to affirm a list of official positions on the character of racism in America. I don't support a major newspaper running a 3,000-word expose about a random woman's bad Halloween costume from two years ago and getting her fired in the process. I don't support mobs of protesters unilaterally deciding to tear down or defacing statues of George Washington, Ulysses S. Grant, Cervantes, and others figures from our collective past. I don't support calls to defund or abolish the police.

The reason I don't support these and other radical acts in response to injustice is that they follow from politically poisonous and destructive assumptions. Those assumptions concern the character of history and moral progress, and the relation of both of them to politics.

Our views of history are ultimately rooted in religion — and specifically in our civilization's inheritance from Christianity and its notion of linear and progressive time. Not only does Christianity reject cyclical accounts of history, but it also affirms the reality of historical ruptures on the path to time reaching its end point. Christianity divides history into discrete epochs or dispensations: before Christ came; after Christ came; and when Christ will eventually return. Those fissures in time and history are hinge moments at which everything changes. Protestant strands of Christianity often go further to emphasize the personal dimension of rupture with the idea of individuals being "born again" in Christ.

In the secularized version of this understanding of history that prevails in our largely post-Christian world, humans themselves (without divine providence or intervention) can accomplish similarly dramatic changes. We saw this at work during the convulsions of the French Revolution, when mobs tore down monuments and ransacked institutions from the past and the revolutionary government reset the calendar to Year 1. The idea of a revolutionary class (the proletariat) founding society anew through an act of purifying violence is also deeply embedded in the Marxist tradition.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

A version of the same impulse can be found in the American political tradition, too — in Thomas Paine's conviction, frequently echoed by Ronald Reagan, that it's possible to "begin the world over again" through force of human will. We hear faint middle-class echoes of this sentiment whenever Americans express a longing to "get a new life," to "start over," or to begin a "new life project."

Whether at a personal or political level, all of this is a fiction. It is no more possible for an individual to make a complete break from his or her past than it is for a political community to start over from scratch. Believing otherwise is delusional. But it's also dangerous — because it raises expectations far beyond their capacity to be fulfilled — and dashed hopes, along with resulting disappointments, overcorrections, and reactions, can bring political ruin.

Classical (pre-Christian) political thought was wiser to include in its reflections on politics the concept of fate. At its most extreme, an emphasis on fate can bleed into fatalism, which produces its own political problems. But our present-day politics would be deepened and enriched by an awareness of fate — of just how constrained we are by a past we will never have the power to fully master or purge.

Aristotle pointed out that "a mistake at the beginning" of a political community sets the pattern of injustice for that community going forward — a pattern that can be ameliorated but never eradicated, because efforts to address the injustice can lead to new injustices, which can prompt unjust reactions, which can require other rounds of reform, which can generate more reactions, and so forth down through the years, decades, and even centuries.

Alexis de Tocqueville adds the observation that as a community addresses and corrects for grave systemic injustices over time, the (smaller) ones that (inevitably) remain come to loom ever-larger in the minds of those who suffer them, so that an act or event that would have been considered a relatively minor injustice in the past comes to take on enormous significance in the present.

In the American context, this implies that the legacy of slavery (our founding mistake) will never be entirely expunged, and that treating that goal as anything more than an unachievable ideal is bound to produce more severe counter-productive cycles of revolution and reaction. It's not enough to keep our eyes on the prize. We need also to keep constantly aware of the possible.

We can improve, and we have to keep trying to do so. But our efforts need to be undertaken in a spirit of moderation — in constant awareness that canceling, firing, and humiliating individuals, like tearing down public monuments outside of legal processes, are deeds that many others will, with reason, view as acts of injustice in their own right. They certainly won't succeed in righting past wrongs, or making it possible for America to be born again, starting over from scratch, cut free from and capable of transcending its immensely complicated history, teeming as it is with people and events both stunningly beautiful and grotesquely ugly, politically magnificent and morally appalling.

Max Weber was right that most of the time politics can be likened to the "slow drilling of hard boards": tedious, difficult, frustrating, often backbreaking, sometimes heartbreaking work, without end. That's how progress is almost always made — not through ecstatic experiences of collective action and grand displays of moral righteousness that open up wholly new futures, but through painstaking trials and tribulations, setbacks and renewed efforts, hemmed in at all times by the capacity to cajole one's fellow citizens to embrace the change.

Achieving that persuasion is especially difficult right now, in our time of partisan and ideological polarization. We can lament this, but pretending it isn't true won't change it, and may even make it worse.

Which is why, now as always, we need to seek justice moderately.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.