The limits of White Fragility's anti-racism

We need more than white guilt to destroy racism in this country

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

White liberals are reading up on racism. The George Floyd protests have only accelerated the "Great Awokening" which has led white liberal opinion on race to move to the left of that of African-Americans on some questions. Thus the 2018 book White Fragility, by the white professor and corporate consultant Robin DiAngelo, which sells itself as a sort of manual for white people looking to fight racism, has spent weeks at the top of The New York Times bestseller list.

It's a laudable impulse. However, while the type of anti-racism advocated by DiAngelo might provide some useful benefits, it is also enervating, distracting, and can even perpetuate its own kind of racial prejudice. We need more than white guilt to destroy racism in this country.

White Fragility tells many stories of the author's corporate seminars (for which DiAngelo is undoubtedly well-paid; diversity consulting is reportedly a multi-billion dollar industry) where she lectures white people about being racist. They typically respond by getting angry, and often quitting her programs — displaying the eponymous white fragility. DiAngelo concludes that all white people, including herself, are unalterably racist. She advocates white people conduct constant introspection about the microaggressions and other acts of prejudice they helplessly commit day after day. "We can interrupt our white fragility and build our capacity to sustain cross-racial honesty by being willing to tolerate the discomfort associated with an honest appraisal and discussion of our internalized superiority and racial privilege," she writes. Racism can only be contained, never defeated.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, there is definitely something to the idea of white fragility. We see it every day when conservatives get furious about people pulling down statues of slave-owning traitors, or when rich liberals react with wounded defensiveness to criticism of their efforts to keep schools segregated. It would be a good thing in general if white people got in the habit of a little introspection when accused of racism. Everyone should be able to ask "Am I the baddie?"

However, that is not the end of the story. For one thing, there is a darker side to this kind of corporate training. Because civil rights legislation allows minority employees to sue if they have been the victim of discrimination, holding an anti-racism training, however ineffective, can be a legal shield against such a lawsuit. For a cynical employer, DiAngelo could literally be participating in systemic racism. If she were more aware of her surroundings and less obsessed with the contents of her own head, she would have addressed this potential problem. She does not.

For another, DiAngelo's thinking is so extreme that it carries its own kind of racial essentializing. In her view all white people without exception are racist, even — indeed, especially — progressive ones. "I believe that white progressives cause the most daily damage to people of color," she writes. Any denial of this is taken as evidence of white fragility and prejudice. It may be true that all white Americans have at least some race prejudice given the gruesome history of this country, but this is blatantly circular reasoning, and raises the question of just what the point of all this self-flagellation is. In DiAngelo's own telling, most of her diversity seminars flop, and studies have shown no benefit whatsoever from her style of training — indeed, some show a backfire effect where people become more prejudiced.

But more importantly, in White Fragility all people of color are portrayed as wise victims of omnipresent white prejudice, who are the only reliable guides to whether whites have atoned sufficiently. If a "person of color trusts me enough to take the risk and [give me feedback], then I am doing well," she writes. In DiAngelo's view, despite her protests to the contrary, whites should be thinking above all about themselves in their interactions with people of color — mainly about what they should apologize for next — and of necessity treating those colleagues not as individual people, but as representatives of an undifferentiated mass of victimhood.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This not only smacks more than a little of the "Magical Negro" stereotype, but also puts up a high barrier between actual communication and learning between races. One end goal of an anti-racist society, presumably, is for people of all races to be able to communicate with each other as individuals. Cross-racial friendship can surely help in this effort — by coming to know one's Black fellow citizens, whites might discover they are regular American human beings like themselves, and indeed that they have a great deal in common. Whites considering their own unconscious biases might help with this, but being taught to view every interaction with a person of color through a racial lens will make it harder, however progressive that lens might be.

More importantly still, DiAngelo has basically nothing to say about what might be done in policy terms about racism. She talks a great deal about "systemic" discrimination, but very little about actual systems — her discussion of affirmative action, for instance, is not about how it might be expanded, but how white people get mad about it. This is a glaring absence especially on the question of economic inequality. As I have written before, economic deprivation is one of the biggest ways that minority groups are victimized in this country. A gigantic redistribution of income and wealth down the social ladder would be perhaps the most effective single attack on racism America could undertake, because it would address many aspects of the problem simultaneously.

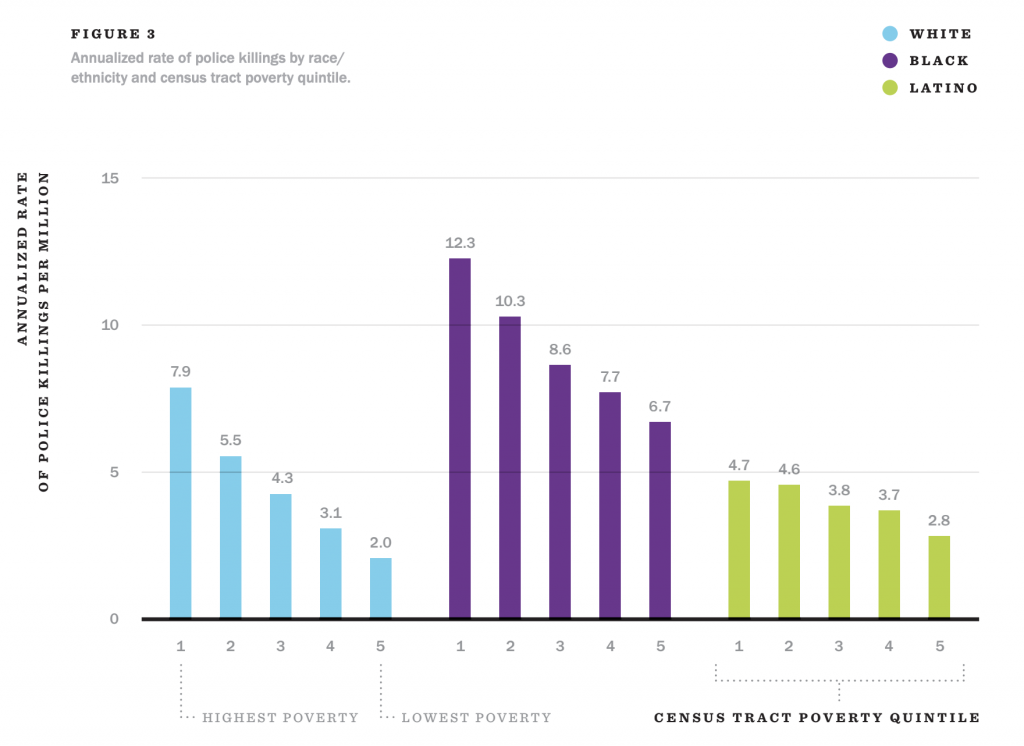

For instance, a recent paper by Justin Feldman for the People's Policy Project found that, for both Black and white Americans, police killings were heavily correlated with the poverty of the census tract in which they occurred:

(Courtesy People's Policy Project)

Moreover, Blacks were also much more concentrated in poverty — 36.6 percent of them lived in the poorest tracts, while the same was true of just 9.6 percent of whites. This fits with other evidence suggesting that an all-out attack on poverty would go some distance towards cutting police violence and mass incarceration, because as we have seen over the past weeks, the main activity of American police and prisons is not solving crime, but keeping a boot on the neck of the disproportionately Black and brown American lower class.

For all her talk about difficult conversations, it is hard to miss how DiAngelo totally elides questions of economic justice that would be uncomfortable indeed for the wealthy corporations and executives that hire her to harangue their employees.

At any rate, it is surely useful for American whites to think about how they might be inadvertently making their workplace an uncomfortable place for their co-workers of color. But it's also useful for whites to think about what they might have in common with their Black and brown fellow citizens. They might form a multi-racial union (another idea that goes unmentioned in the book). They might realize that though Black Americans have it worse, white Americans are still not doing great compared to residents of peer nations — they are impoverished, imprisoned, and killed by police at shocking rates; live shorter and less healthy lives, pay through the nose for lousy health care, and on and on.

Racism must be eradicated, partly because it forestalls the kind of multi-racial, working-class political coalition that could make this country a better place to live for everyone. But it seems you won't learn that at a corporate diversity seminar.

Want more essential commentary and analysis like this delivered straight to your inbox? Sign up for The Week's "Today's best articles" newsletter here.

Ryan Cooper is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. His work has appeared in the Washington Monthly, The New Republic, and the Washington Post.