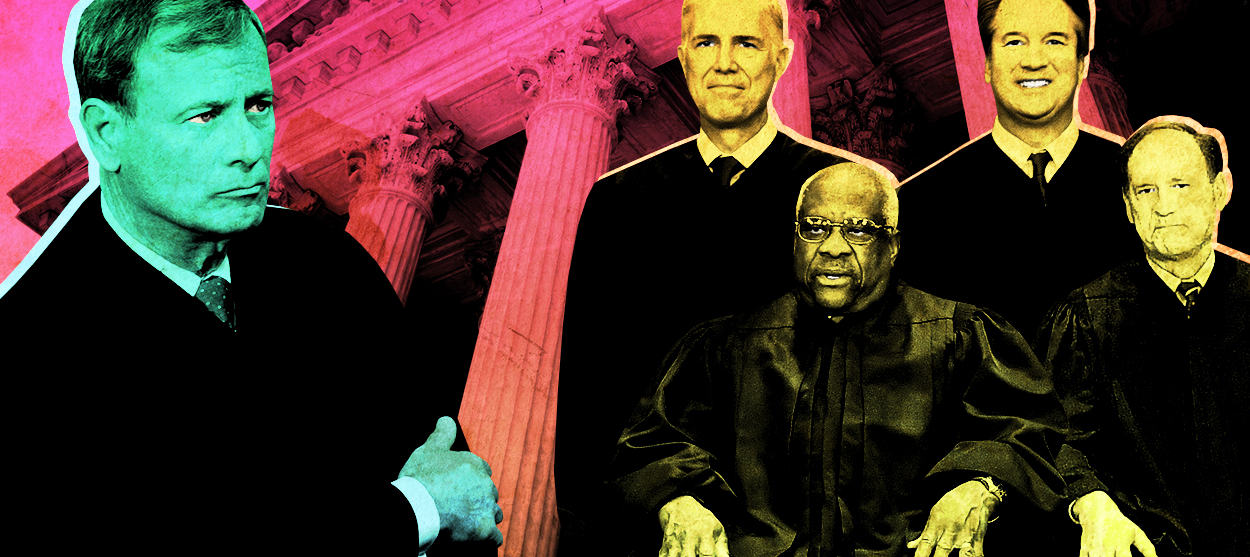

The Supreme Court's competing visions of conservatism

In Monday's abortion decision, Chief Justice John Roberts once again demonstrated he follows a different set of conservative principles

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With Monday's Supreme Court's decision in June Medical Services L.L.C v. Russo, Americans are learning that there are at least two kinds of conservatism in the United States — and that, at least on some issues, Chief Justice John Roberts affirms one kind while his fellow Republican appointees to the high court affirm the other.

Just four years ago, shortly after the death of conservative stalwart Antonin Scalia, a 5-3 majority of the Supreme Court voted in Whole Woman's Health v. Hellerstedt to strike down a Texas law that required doctors working in abortion clinics to maintain admitting privileges at nearby hospitals. As he often did on social issues, swing-vote Anthony Kennedy joined the liberals in the majority and Roberts stood with conservatives in dissent. In his opinion for the majority, Justice Stephen Breyer argued that requiring doctors to have admitting privileges at hospitals forced many abortion clinics to close and therefore placed an undue burden on women in Texas seeking to exercise their reproductive rights.

In the intervening years, President Trump has appointed two conservatives to the high court — Neil Gorsuch to succeed Scalia, and Brett Kavanaugh to succeed a retired Justice Kennedy. All else being equal, one would expect this more right-leaning court to have gone the other way on Hellerstedt. Yet on Monday, the Supreme Court announced a decision about a substantially similar law in Louisiana — and struck it down, this time with Roberts joining the liberal majority.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Lest people conclude that Roberts has suddenly lurched leftward to become a substantive defender of abortion rights, the chief justice's rationale for joining Justices Breyer, Ginsburg, Kagan, and Sotomayor in Russo was based not on him changing his mind about Breyer's undue burden test but rather entirely on the principle of stare decisis — or deference to precedent. Roberts thought the court's decision in Hellerstedt was wrong, but he still considers it a binding precedent that applies to the Louisiana case, and so the court must abide by it. As if to underscore the kind of conservatism he aims to uphold in Russo, Roberts' concurrence quotes none other than Edmund Burke, whose ideas about the fallibility of reason and the need for deference to tradition have played such an influential role in the development of conservative ideas.

Not that Burke has been influential on all conservative ideas. Other kinds of conservatism descend from different sources. At the furthest pole from Roberts' Burkean restraint is the absolutist natural law theorizing of Clarence Thomas, whose fiery dissent in Russo makes clear what has been plain for many years — which is that Thomas sees little value in stare decisis at all. If he thinks a case was wrongly decided, he will vote to overturn it, no matter how long it has been the law of the land. Thomas is unwaveringly certain that he knows what the Constitution requires and permits, he thinks these standards are fixed for all time, and what matters for him is applying these standards correctly and stamping out the jurisprudential error wherever he finds it.

Another way to describe the difference is to say that Roberts is a conservative pragmatist or institutionalist, while Thomas is a conservative ideologue. The court's other three conservative justices appear to fall somewhere in the middle, usually leaning more in Thomas' ideological direction, but sometimes displaying the kind of flexibility Roberts has recently begun to evince.

Ideological conservatives have long despaired at how difficult it can be to pre-judge what kind of justice a nominee will become once he or she reaches the bench. Some, like Scalia and Thomas, prove themselves to be steadfast defenders of ideological conservatism. But others, like Kennedy, who became a great champion of gay rights and voted to uphold the right to abortion in Planned Parenthood v. Casey (1992), veer off in other directions, becoming full-throated champions of causes that ideological conservatives strongly oppose. Still others, like David Souter, who joined in the majority with Kennedy and Sandra Day O'Connor in Casey, end up favoring precedent and judicial restraint, even when it lets stand poorly decided decisions from the past.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Between Roberts' recent rulings against the Trump administration and his willingness to place precedent over ideological purity in Russo, it's tempting to conclude that the chief justice, who spoke at his confirmation hearing about seeing his role as that of an umpire neutrally calling balls and strikes, is following in Souter's footsteps, ready and willing to disappoint ideologues by a consistent embrace of institutional and judicial caution and restraint. (Roberts did something similar in 2012 when he voted with the court's liberal faction to uphold the Affordable Care Act.)

Yet Roberts' record shows that he's more than willing to overturn longstanding precedents when it comes to campaign finance and the power of labor unions. In Citizens United (2010), for example, Roberts voted with the majority to strike down campaign finance regulations on the grounds that they violate the free speech provision of the First Amendment. He used a similar rationale in Janus (2018) to overturn a unanimous 1977 decision that permitted public sector labor unions to collect fees against the wishes of employees.

That raises the question of whether Roberts has changed his views in the last couple of years to embrace a greater degree of judicial restraint — or if, more likely, he believes in showing greater deference to precedent when it comes to social issues and other matters he judges to be especially risky for the high court's reputation. The latter would make Roberts a synthesis of Souter and Kennedy — a kind of situational Burkean who is perfectly willing to stake out more ideological positions when it comes to issues wrapped up with economic liberty.

Whatever the case, Roberts is fast becoming a significant problem for ideological conservatives, and perhaps especially social conservatives, who always seem to find themselves in the minority on the high court, no matter how many justices Republican presidents manage to fill.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.