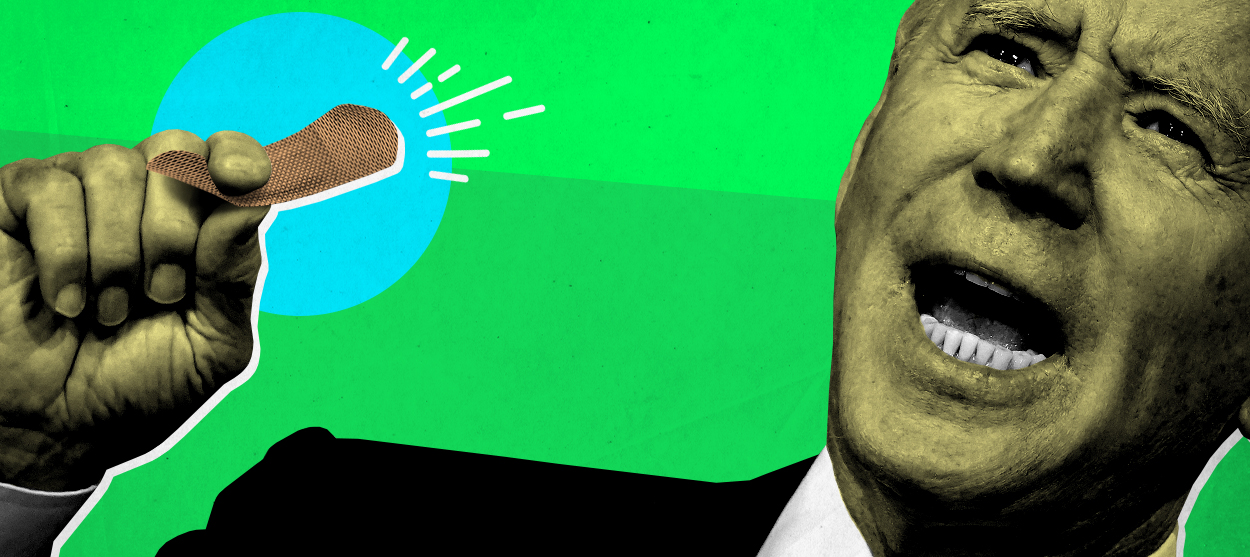

Biden can't heal the country

Our national sickness needs more than a Band-Aid

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Winding down his last week on the campaign trail, Democratic nominee Joe Biden is preaching a message of healing. "Today I'm here at Warm Springs because I want to talk about how we're going to heal our nation," he said Tuesday from a small Georgia town where Franklin Delano Roosevelt built a resort for polio patients. "The divisions in our nation are getting wider," Biden continued:

[M]any wonder, has it gone too far? Have we passed the point of no return? Has the heart of this nation turned to stone? I don't think so. I refuse to believe it. [ ... ] I'm running as a proud Democrat, but I will govern as an American president. I'll work with Democrats and Republicans. I'll work as hard for those who don't support me as for those who do. [ ... ] And yes, we can restore our soul and save our country. [Joe Biden, via Rev]

There's an alluring normalcy and comity here, but Biden's promise is not and cannot be true. Should he be elected, Biden may be able to make the presidency less of an aggravating factor in our political division, if only by making it easier for Americans to forget about the president entirely for longer stretches than President Trump's omnipresence has permitted these past four years. But forgetting our division is not the same as healing it.

What Biden can realistically offer, if I may extend his medical metaphor, is a Band-Aid. I don't mean that in the dismissive sense in which it is often used — a Band-Aid is not nothing. Electing Biden might be analogous to cleaning up a skinned knee, taking out the bits of gravel embedded in the cuts, and putting a bandage on top. This is helpful for healing, but it doesn't heal. The body must heal itself.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

It is questionable whether there is such a thing as a "president who doesn't divide us, but unites us," as Biden pledges to be. I suspect the bully pulpit and scope of power of the modern office don't allow for that possibility. There is simply too much at stake for the position to be anything but divisive.

That's so even of the comparatively anodyne Biden, whose victory nine in 10 Trump supporters believe would "result in lasting harm to the country." (Exactly the same proportion of Biden supporters say the same of Trump's potential re-election.) A 2019 study found four in 10 Democrats and Republicans think the opposing party is "not just worse for politics" but "downright evil." The common thinking among Biden's opponents, enthusiastically propagated by Trump himself, is that Biden is a Trojan horse for socialism and the radical left, albeit maybe an unwitting one. These beliefs won't dissipate after the election, no matter how much Biden reaches across the aisle. Optimism loses to fear, disgust, and tribalism.

Yet even if we say, for the sake of argument, that a President Biden could be a net force for unity, we're left with the same problem: It's not enough. The president can't heal our country's division. The Trump administration is at least as much a symptom as a cause of the illness in our politics, and that illness won't go away with Trump's departure, whether next year or in 2025. Clean away the gravel, but the knee is still skinned.

Our illness is a result both of culture and institutions of governance. The cultural etiology is what my colleague Matthew Walther has dubbed "middle-finger voting," politics for the sake of "seeing one's real or perceived enemies discomfited." The point is not governance, but power for its own sake; not adherence to principles but punishing those we deem a threat to us and ours.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

This mindset is not universal among Americans, and most of those who call their partisan opponents "downright evil" likely have friends and family whom they love across party lines. But in the turn from those specific relationships to national politics, a fever sets in. "[W]hat defines Republicans and Democrats isn't programs or beliefs or ideology," writes J.D. Tucille at Reason; "it's achieving power and destroying the enemy in the process." When "platforms and ideas don't really matter," he adds, "there's no room for finding common ground or cutting deals" on policy, because uncompromising control is the very point.

Tucille argues "the only way to keep the peace is to make sure there's no prize to be won," to reduce the power available so partisan animosities are accordingly scaled down. Make the presidency less divisive by making it less desirable. I agree, wholeheartedly. But I can't see how that would happen without dramatic change to our political culture, and I can't see how the political culture would change while our institutions constantly reinforce it, and I can't see how the institutions will change while the culture — well, you get it.

Biden says he can interrupt that vicious cycle at the cultural node. However sincere, he's wrong. A president might be able to refrain from exacerbating our political division, but he can't heal it. We have to heal ourselves, culturally and institutionally, and I'm not sure we'll prove capable. I'm not sure we really want to try.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.

-

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?

Crisis in Cuba: a ‘golden opportunity’ for Washington?Talking Point The Trump administration is applying the pressure, and with Latin America swinging to the right, Havana is becoming more ‘politically isolated’

-

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predators

5 thoroughly redacted cartoons about Pam Bondi protecting predatorsCartoons Artists take on the real victim, types of protection, and more

-

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorism

Palestine Action and the trouble with defining terrorismIn the Spotlight The issues with proscribing the group ‘became apparent as soon as the police began putting it into practice’

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred