Why Trump failed

Trump's mind ran on golden visions, but he entrusted their execution to toadies and backbiters

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I have always liked Cyril Connolly's memoir, not because it is an especially edifying book, but because its title, Enemies of Promise, is so wonderfully suggestive. Promise always has its enemies. Now that it appears all but certain that Joe Biden will be the next president of the United States, it is worth asking what these were in the case of Donald Trump, many of whose supporters consider him the greatest political talent of the last decade.

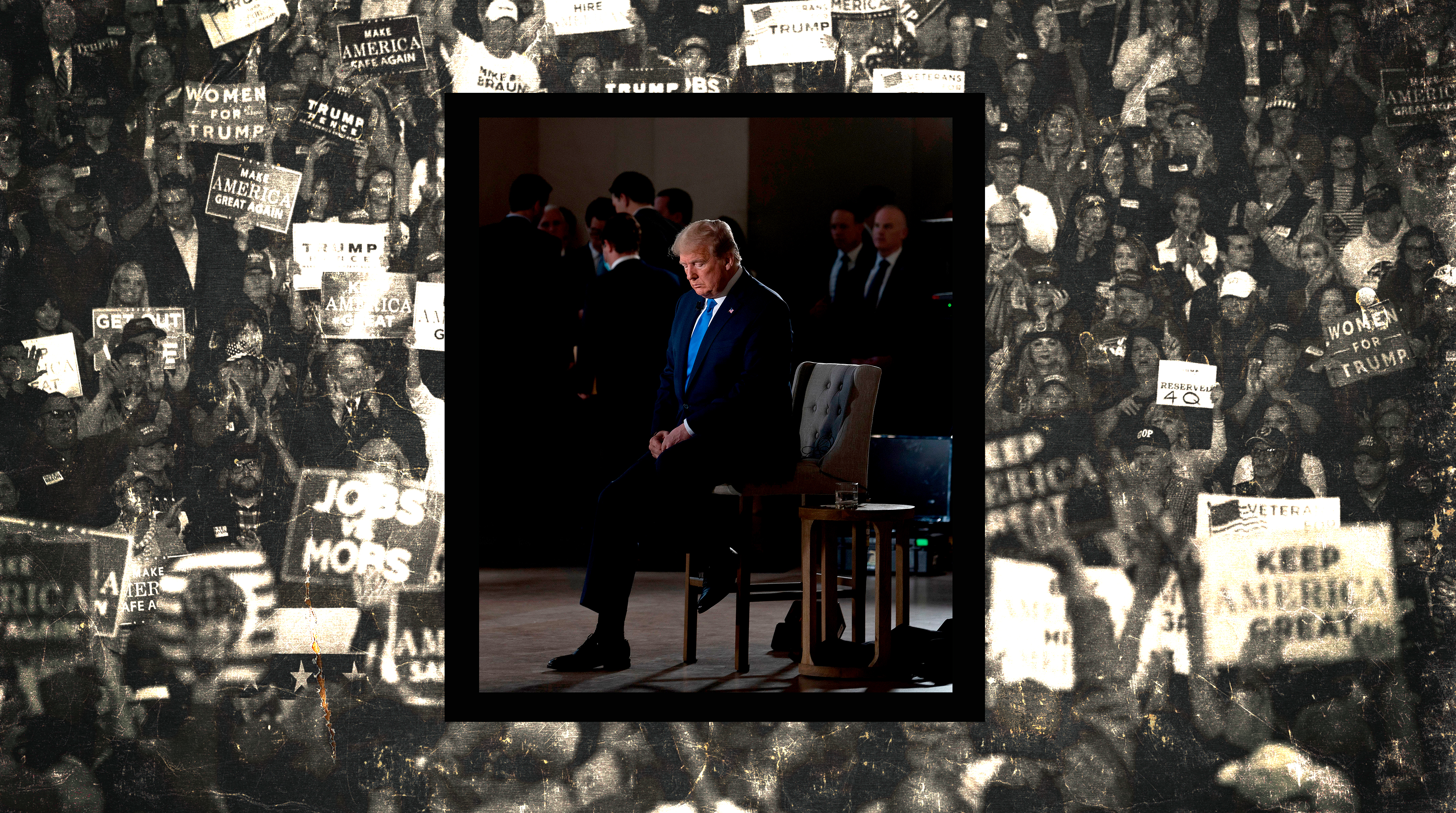

The first thing to be said about this assessment is that it is true, but only in a limited sense. No American politician in my lifetime has been a more skilled campaigner than the former host of Celebrity Apprentice, with the possible exception of his immediate predecessor in office, whom he resembles in several crucial senses. Trump, every bit as much as Barack Obama, belonged not to the present of digitized campaigning but to the oral past, the vanished era of political barnstorming when families brought picnic lunches and listened with rapt attention to William Jennings Bryan and Teddy Roosevelt. It is almost impossible to convey what his rallies were like to those who never attended one of them. I for one did not find the experience edifying, but I am glad that I will be able to describe it to my children one day.

Trump's showman abilities expanded beyond the scene of his rallies to his use of television and social media, of which he was also a master. What he inspired above all was a fanatical loyalty, and the fantastic belief that the mere act of voting for him was some kind of life-affirming existential gesture. Within this narrow sphere he was without rival.

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

This brings us back to the enemies of Trump's promise, such as it was. The most important was his own almost total indifference to the actual business of governing. On trade, manufacturing, infrastructure, entitlement spending, public debt, and even (once upon a time) health care, his instincts were sound, but when it came time to act upon them the work was left to the exhausted remnants of the conservative intellectual class. These toadies and backbiters did far more damage to his electoral prospects than his enemies, and his administration, begun with the splendor of a victorious 19th-century republic, ended as a seraglio. The almost painfully unimaginative Mnuchin, the penny-pinching Mulvaney, the mendacious Tillerson and the oleaginous Pompeo, the sinister Miller, perhaps most of all Kushner, the failed apostle of Trumpism to the Upper West Side: the history of this White House is a long roll of names, each figure more ineffectual than the last. These men betrayed Trump's ambitions and were the architects of a thousand failed schemes of their own.

Trump was at his best acting unilaterally: canceling student loan interest, proclaiming a nation-wide moratorium on evictions, nearly canceling (above the cries of screams of the eunuchs at court) the entire outstanding fiscal obligations of Puerto Rico. His greatest achievement was wholly negative: He was the first president in nearly two decades not to enlist the United States in a meaningless foreign war. This is no small feat given the records of his two immediate predecessors, which bequeathed to us, among other things, the greatest refugee crisis in world history. But for many it is hard not to imagine that he might have done much more.

Trump's mind ran on golden visions: the limitless vista of a continent-spanning wall, well-organized columns of troops lining the broad avenues of bright cities, the spire of a skyscraper in the crimson of a Manhattan sunset, beyond which it was just possible to see the smiling face of an angel. He assured us that these visions were not, as his enemies insisted, the delusions of a voluptuary, but intimations, as it were, of a higher reality; that what was in the process of being realized was Aᴍᴇʀɪᴄᴀ, not the sordid decadence of the global counting house that it has become but the ideal glory of the republic, at last fulfilled.

Those of us who know (and knew) better should not continue to chase these phantoms. The music has retreated to the empyrean; the stars are dim. The wings of the angel of history flutter past, on an unrelated errand.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Matthew Walther is a national correspondent at The Week. His work has also appeared in First Things, The Spectator of London, The Catholic Herald, National Review, and other publications. He is currently writing a biography of the Rev. Montague Summers. He is also a Robert Novak Journalism Fellow.