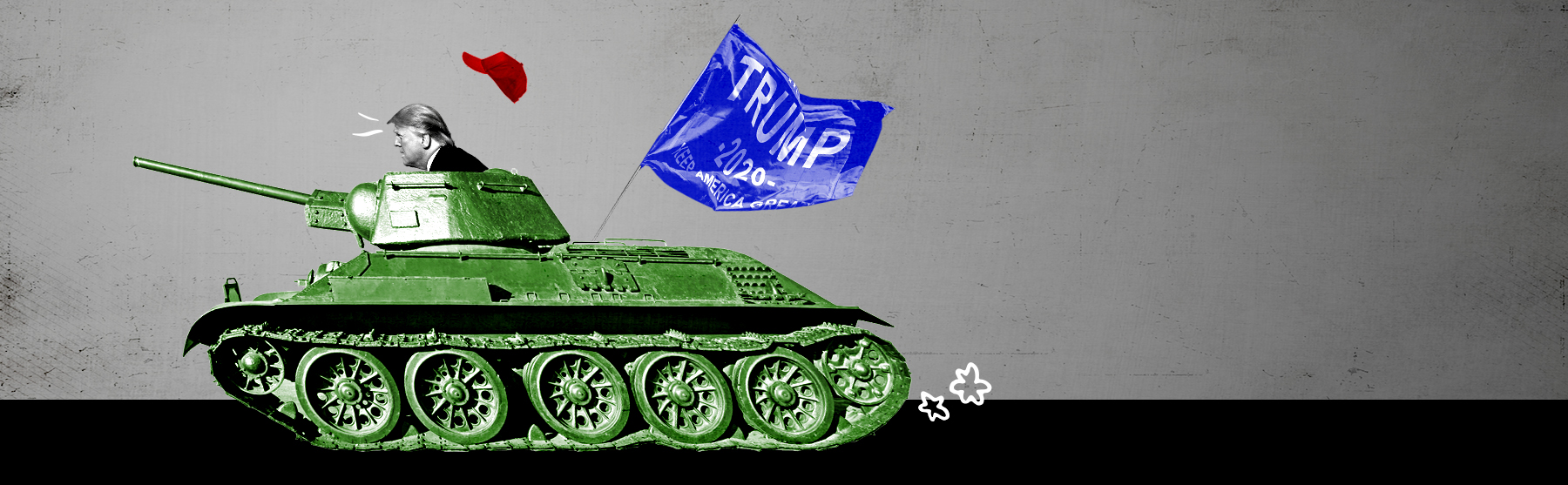

What would actually happen if Trump tried the 'martial law' idea?

For one, his co-conspirators would likely end up in prison

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

President Trump could "basically rerun an election" by sending the military into swing states, said Trump's first national security adviser, Michael Flynn, in a Newsmax interview last week. Martial law isn't a big deal, Flynn continued. "It's not unprecedented," he said. "I mean, these people out there talking about martial law like it's something we've never done — martial law has been instituted 64 times."

Flynn isn't alone in his open enthusiasm for precisely the military junta scenario the president's supporters have spent four years dismissing as a fever dream of Trump Derangement Syndrome. Lin Wood, an attorney who sued to prevent the certification of the Georgia presidential election results, tweeted Saturday that "[p]atriots are praying" Trump will "impose martial law in disputed states." Commenters at TheDonald.win, an online forum for supporters of the president, thrilled at the idea of a "mostly peaceful martial law declaration" but wondered, absurdly, whether it would accommodate their teenagers' travel home from college or their wives' scheduled c-sections. And then there's Trump himself, who met with Flynn and other allies in the Oval Office this past Friday. The president reportedly expressed interest in Flynn's idea.

Could this actually happen? Though it may simply be normalcy bias at work, I can't really imagine federal troops marching through U.S. streets, scooping up voting machines and tossing anyone who objects before a military tribunal. Moreover, Trump's other advisers in the Friday meeting reportedly opposed the plan in forceful terms, and a statement from Army leadership the same day made clear the military would take no role "in determining the outcome of an American election."

Article continues belowThe Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

That ought to be the end of a discussion that never should have begun. But this is Trump, a president who lackadaisically declared a national emergency so he could take money from Pentagon coffers to pursue a policy agenda Congress had specifically declined to fund. In that context, a lame-duck martial law attempt seems — well, not likely, but not entirely inconceivable. But still: What exactly would Generalissimo Trump do? What possible legal authority could he claim? With less than a month left in office, does he even have time to try what Flynn recommends? I put these questions and more to Cato Institute legal scholar and Overlawyered founder Walter Olson in an email interview this week.

There are really two topics at issue here, Olson told me: martial law and the Insurrection Act of 1807. Under martial law, he summarized, "civil liberties are suspended," so "military commanders can issue orders to civilians" as well as "arrest and mete out punishment based on tactical needs of war rather than the civilian law on the books." Martial law has been declared 68 times in the United States, per a recent tally by the Brennan Center for Justice, and only on one occasion has it happened on a national scale. (Most instances on the list were limited to a single city or county and often concerned local labor disputes or rioting.)

That single occasion was President Abraham Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus rights to suppress dissent during the Civil War. But in Ex parte Milligan (1866), the Supreme Court ruled Lincoln had overstepped his legitimate bounds. This ruling is "key" to understanding the president's martial law powers today, Olson said. It means "the president cannot simply declare martial law at his whim. There must be a state of invasion or insurrection such that ground is actually contested, and resort to conventional civil courts and authority must have collapsed." Absent those conditions, the court said in Milligan, martial law is "a gross usurpation of power," and in fact "can never exist where the courts are open."

The courts are open now, which means any declaration of martial law — including in the six states Flynn targeted — would be illegal. "Courts would not be afraid to recognize this as reason to strike down acts pretending to martial law authority," Olson said, just as they haven't been afraid to smack down specious election challenges. That might not stop Trump, Olson allowed, but it would stop many of the people he'd need to execute this plan. And even if their constitutional oaths did not constrain them, there would be "very real personal consequences for both civilian and military administrators should they go along" with such an unlawful proposal, Olson noted, as career bureaucrats and officers undoubtedly realize. (The Army statement is an indicator of this very understanding.)

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

The Insurrection Act gives Trump no additional leeway here. It does provide an exception to the general prohibition (under the Posse Comitatus Act) on using federal troops to enforce domestic law. But those exceptions — which typically involve violent insurrection — aren't applicable in this scenario. Furthermore, Olson told me, "there is a separate set of laws in which Congress has not only disallowed, but even chosen to make a crime, actions by federal troops or officers that interfere with the right to vote."

The "thing to remember about the Insurrection Act," Olson added, "is that it doesn't allow federal troops to enforce anything but already-prevailing federal, state, and local law. It does not authorize martial law in the sense of deprivation of ordinary civil liberties, special tribunals, irregular punishment, street justice, cutting off resort to the courts, etc." (In 2006, the annual National Defense Authorization Act included a provision which changed that, allowing the president to impose martial law via the Insurrection Act. Uproar was widespread, however, and in early 2008, Congress repealed the change.) So even if the Insurrection Act were applicable (which it isn't), and even if there weren't additional legal protections against federal military meddling in state-administrated elections (which there are), deploying troops under this authority still wouldn't result in martial law.

So Trump may well be interested in Flynn's idea. But, as he is surely being told by his aides, particularly career civil servants who recognize the reality of the election results, he has no legitimate power to pursue it. He also won't find the coconspirators he needs in the military and judiciary if he tries.

As the Supreme Court wrote in Milligan, "[b]y the protection of the law human rights are secured; withdraw that protection, and they are at the mercy of wicked rulers or the clamor of an excited people." For all their flaws and inconsistencies, our founders knew, contra Flynn, that martial law is a big deal. They wrote a Constitution to protect "every right which the people had wrested from power during a contest of ages," Milligan said, even in "troublous times ... when rulers and people would become restive under restraint."

That Constitution — and Milligan, Posse Comitatus, and the Insurrection Act of 1807 — insist Trump cannot declare martial law in these troublous times. If he attempts it, he will fail.

Bonnie Kristian was a deputy editor and acting editor-in-chief of TheWeek.com. She is a columnist at Christianity Today and author of Untrustworthy: The Knowledge Crisis Breaking Our Brains, Polluting Our Politics, and Corrupting Christian Community (forthcoming 2022) and A Flexible Faith: Rethinking What It Means to Follow Jesus Today (2018). Her writing has also appeared at Time Magazine, CNN, USA Today, Newsweek, the Los Angeles Times, and The American Conservative, among other outlets.