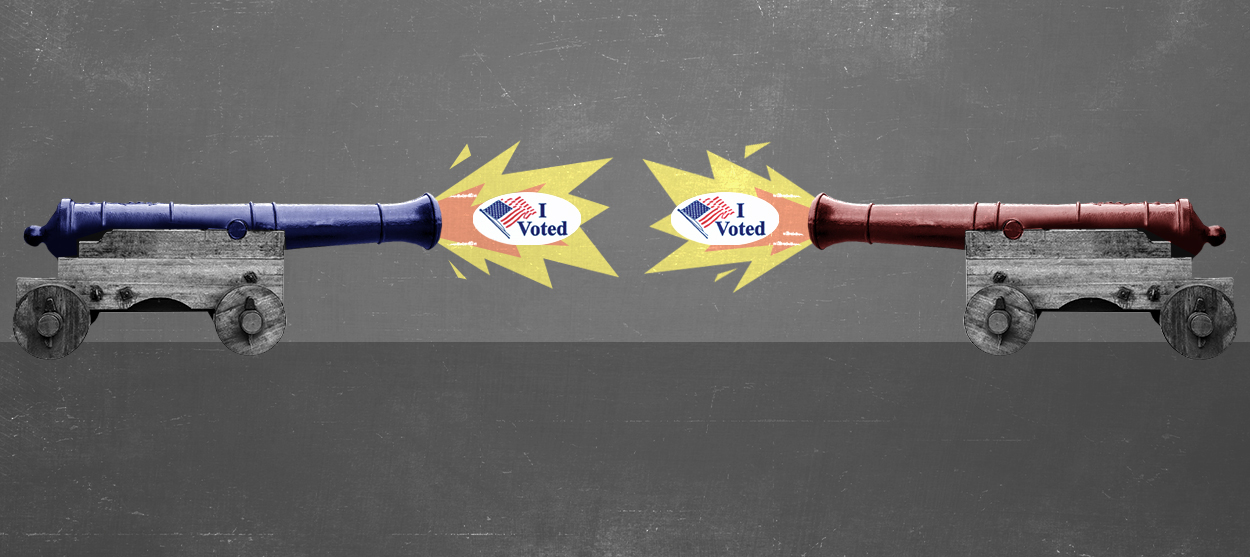

The revealing showdown on voting rights

Republicans can win a clean fight. Why don't they act like it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Even in an era marked by polarization and hyperbole, it's noteworthy just how rancorous the language has become on a question fundamental to democracy: How easy or hard should it be to vote?

On Monday, voting rights advocate Stacey Abrams called Republican efforts in Georgia, Arizona, and New Hampshire to make it more onerous to vote the "largest push to restrict voting rights since Jim Crow." Meanwhile that same day, the conservative National Review described H.R. 1, the omnibus voting rights bill that passed the House last week without a single Republican vote, "a radical assault on American democracy, federalism, and free speech" the likes of which hasn't been seen "since the Alien and Sedition Acts" of 1798.

Those who think H.R. 1 goes too far have a point. As Charlie Sykes argues in The Bulwark (where I participate in a weekly podcast), the bill is "bloated, overstuffed, and of dubious constitutionality," blending reasonable restrictions on gerrymandering with a sweeping federalization of election law and provisions that would amount to a genuinely ominous regulation of political speech.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But rushing to denounce the bill without paying attention to the context in which it has arisen — treating it as some kind of ruthless partisan power grab that effectively comes out of nowhere, as conservatives are doing — is dishonest in the extreme. Republicans have put us on the path to this showdown over voting rights, and what they're doing in states around the country shows they have no intention of backing down from their brinksmanship. Until they do, Democrats are bound to play hardball in response — and for very good reason.

America's electoral system includes numerous institutional means by which minorities can check the will of majorities. Each of these checks is defensible in the abstract and in isolation from the others. But when a single region or party manages to use these checks to prevail consistently and systematically over another comparably sized bloc of voters, these checks can become civically poisonous.

That's precisely what's been happening in the United States in recent years.

The tendency of Democrats to cluster into relatively few states gives Republicans a sizable advantage in the Senate, which assigns the same number of representatives to every state regardless of population. The GOP enjoys a similar advantage in the Electoral College, where the partisan skew is now so great that in 2020 Donald Trump came within roughly 50,000 votes of winning the presidency despite losing the popular tally by 7 million. Republican strength in competing for the Senate and presidency also gives the party outsize influence on making lifetime appointments to the judiciary, where federal judges and Supreme Court justices pronounce on the constitutionality of attempted changes to these very laws and rules.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Then there's the gerrymandering of state legislatures and the U.S. House of Representatives, which Republicans in states around the country have been pursuing aggressively in order to enhance their hold over power in the most democratic branches of our political system.

But all of those advantages aren't enough for Republicans. Convinced that Democrats gain when voting becomes easier (by allowing early voting, voting by mail, unrestricted absentee balloting, curbside voting, and other procedures), Republicans have set about making it harder. Through most of his presidency, Donald Trump intensified such moves by regularly lying about an imaginary scourge of voter fraud disadvantaging the GOP. But that's nothing compared to the Big Lie he's been telling since his defeat in last November's election.

With Trump insisting the election (and thus the presidency) was stolen from him, Republican officials around the country have been moving to raise obstacles to exercising the franchise. As of last month, 43 states have introduced 253 bills that would restrict voting. Those in Georgia, where Trump and two Republican Senate candidates narrowly lost their elections in recent months, are among the most draconian. One bill would end no-excuse vote-by-mail and allow the partisan legislature to usurp the power of state and local election officials. Another would limit weekend voting (including the Souls to the Polls program that encouraged voting at church on Sundays) and even prevent people and groups from bringing food or drink to voters forced to stand in line for hours while waiting to cast ballots.

National Review may well be right that attempts to roll back these kinds of restrictions by federalizing election law are ill-advised and even unconstitutional. But why not call the restrictions wrong and efforts to pass them outrageously antidemocratic? Even if we assume that the U.S. Constitution permits state legislatures to require large numbers of Americans to stand in line for hours on a single day of voting in order to have a say in who will represent them, that doesn't mean those legislatures are right to do so. That many of them are making these moves on the basis of flagrant lies peddled by a conspiracy-addled conman only makes it more galling.

And more than galling.

The standard line on vote suppression is either that it's overtly racist (because those most disadvantaged are members of minority groups) or that it's driven by such electoral mercilessness that concerns about the racial disparity of the impact gets treated as an irrelevancy. Republicans want to win power, in other words, and they don't much care about who gets hurt in the process (as long as the ultimate victim is the Democratic Party).

But the peculiar fact is that in 2020 expanded ballot access didn't just help Democrats. It boosted Republicans, too, contributing to the party's significant gains with Hispanics and to its more modest but still noteworthy increase in support from Black voters. And of course it also helped with the much whiter voters who more typically cast ballots for Republicans — voters who live in states where legislatures and governors are now nonetheless working to make voting more difficult in future elections.

Republicans are acting like a shrinking or dying party that can only win by placing obstacles in the way of its opponents making it to the polls — when the evidence shows that the GOP is very much in the game and could benefit just as much as Democrats by lowering barriers to voting. How pathetic is that?

A self-possessed party would be encouraging people to vote, confident that its message will win plurality or even majority support. Instead, Republicans have shamefully talked themselves into rigging the system in their own favor. They should not be surprised the competition is unwilling to let them get away with it.

Damon Linker is a senior correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also a former contributing editor at The New Republic and the author of The Theocons and The Religious Test.

-

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospective

Gwen John: Strange Beauties – a ‘superb’ retrospectiveThe Week Recommends ‘Daunting’ show at the National Museum Cardiff plunges viewers into the Welsh artist’s ‘spiritual, austere existence’

-

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?

Should the EU and UK join Trump’s board of peace?Today's Big Question After rushing to praise the initiative European leaders are now alarmed

-

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problem

Antonia Romeo and Whitehall’s women problemThe Explainer Before her appointment as cabinet secretary, commentators said hostile briefings and vetting concerns were evidence of ‘sexist, misogynistic culture’ in No. 10

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration

-

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?

'Seriously, not literally': how should the world take Donald Trump?Today's big question White House rhetoric and reality look likely to become increasingly blurred