What the critics are saying about Hokusai: The Great Picture Book of Everything

Master printmaker‘s Japanese ink drawings put on display by British Museum for the first time

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

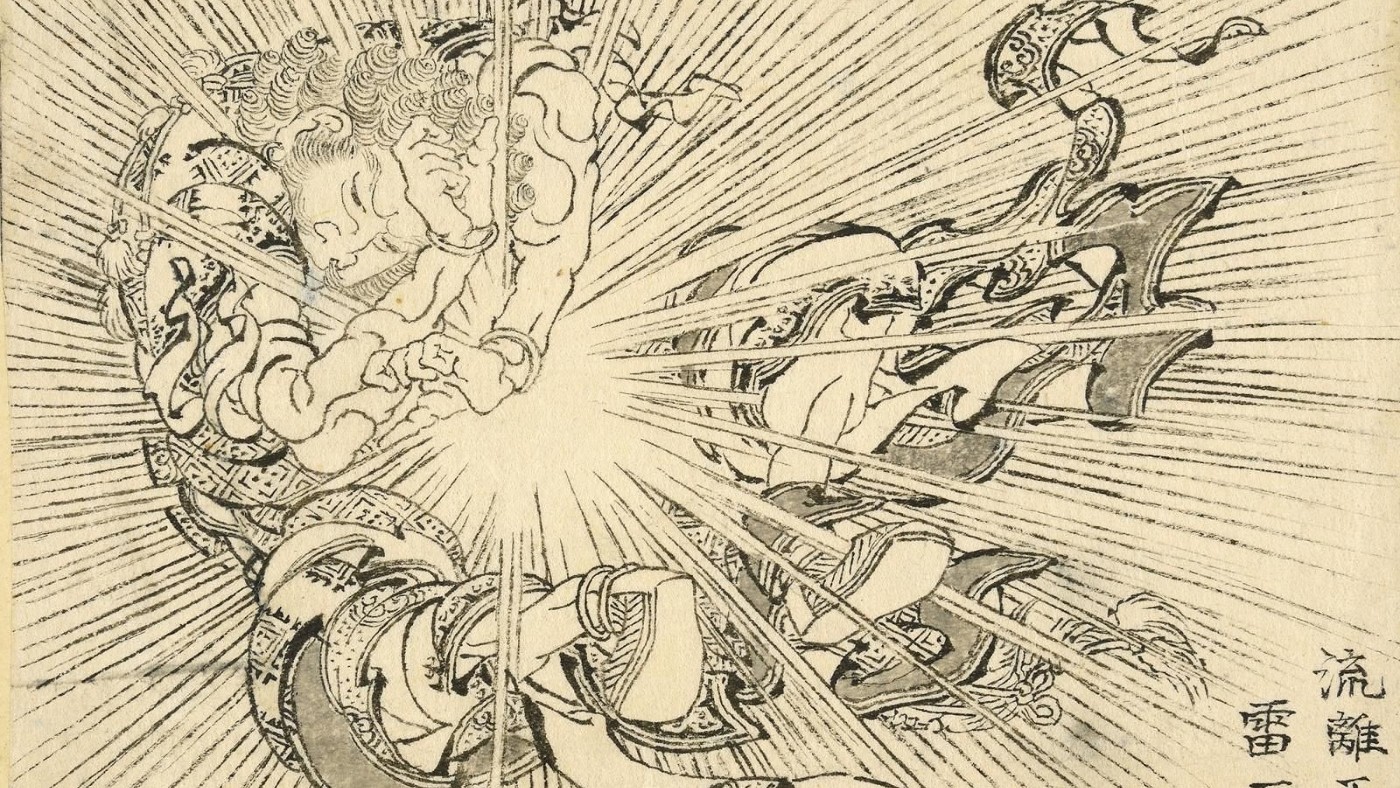

In 2019, “a modest wooden box” containing 103 Japanese ink drawings was consigned for sale at an auction house in Paris, said Rachel Campbell-Johnston in The Times. Unremarkable as it seemed, it was in fact “a treasure chest”: its contents were revealed to be the work of the master printmaker and painter Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849), whose print Under the Wave off Kanagawa ranks as “one of the world’s most recognisable artworks”.

The discovery shed invaluable new light on the great artist’s career. In the late 1820s, when many of the drawings were created, Hokusai was believed to have been going through a “fallow” period: “he had suffered a stroke; his second wife had died; he was struggling financially”.

Yet as the drawings attest, he did not stop working. The works in the box, it transpires, form a significant chunk of a “hugely ambitious” project designed to create a visual encyclopaedia of the whole world. Featuring depictions of everything from animals both observed and imagined to “primordial deities” and “questing Buddhist monks”, the cycle is a masterpiece of Japanese art; yet for reasons unknown, it was never published.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Now, at long last, we finally have the chance to see it for ourselves. The British Museum, which eventually acquired the drawings, has put them on public display for the first time in an extraordinary exhibition that will run until the end of January. It is an unmissable event: to look at these works is to “lose yourself in a world where a spirit of wonder roams free”.

This is a “captivating” show, agreed Laura Cumming in The Observer. The drawings themselves are “no bigger than postcards”, yet their depth of detail is astonishing. His drawing of a camel – an animal he may possibly have seen up close – also incorporates an orangutan, a black fox and “a raccoon-dog flying off into the white space that remains”; an image of men brewing rice wine, meanwhile, sees them deploying “a Heath Robinson contraption involving pumps, presses and cantilevered poles upon which they balance to comical effect”.

Hokusai’s graphic inventiveness “startles every time”: rain “strafes the page in needle-fine lines”, while eyes are rendered as “a staggering grammar of commas, hyphens, cedillas and full stops, minutely inflected to describe each individual face”.

Hokusai’s attempt to catalogue the entire world was a fantastically quixotic undertaking, said Jonathan Jones in The Guardian. The project is all the more remarkable for the fact he never actually left Japan, the 19th century rulers of which had “strictly limited all contact with the outside world”.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Nevertheless, his imagination runs wild. Armed with only “unreliable” information, Hokusai gives us stunning depictions of China and fantastical images of India; an Indian elephant “lowers its head to the ground in comic exhaustion, as if tired of the weight of its tusks and trunk”.

His real achievement, however, was the innovative way he captured nature, distilling water forms and landscapes into a semi-abstract, “stylised shorthand” – something none of his European contemporaries would have dreamt of doing. Hokusai’s art was decades ahead of its time. If you can make it to this display of “masterpieces” before it closes, you must. The drawings are small, but “the rewards are massive”.

British Museum, London WC1; britishmuseum.org. Until 30 January

-

Switzerland could vote to cap its population

Switzerland could vote to cap its populationUnder the Radar Swiss People’s Party proposes referendum on radical anti-immigration measure to limit residents to 10 million

-

Political cartoons for February 15

Political cartoons for February 15Cartoons Sunday's political cartoons include political ventriloquism, Europe in the middle, and more

-

The broken water companies failing England and Wales

The broken water companies failing England and WalesExplainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

A thrilling foodie city in northern Japan

A thrilling foodie city in northern JapanThe Week Recommends The food scene here is ‘unspoilt’ and ‘fun’

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriors

Samurai: a ‘blockbuster’ display of Japan’s legendary warriorsThe Week Recommends British Museum show offers a ‘scintillating journey’ through ‘a world of gore, power and artistic beauty’

-

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brand

BMW iX3: a ‘revolution’ for the German car brandThe Week Recommends The electric SUV promises a ‘great balance between ride comfort and driving fun’

-

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ return

Arcadia: Tom Stoppard’s ‘masterpiece’ makes a ‘triumphant’ returnThe Week Recommends Carrie Cracknell’s revival at the Old Vic ‘grips like a thriller’

-

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to Lagos

My Father’s Shadow: a ‘magically nimble’ love letter to LagosThe Week Recommends Akinola Davies Jr’s touching and ‘tender’ tale of two brothers in 1990s Nigeria

-

Send Help: Sam Raimi’s ‘compelling’ plane-crash survival thriller

Send Help: Sam Raimi’s ‘compelling’ plane-crash survival thrillerThe Week Recommends Rachel McAdams stars as an office worker who gets stranded on a desert island with her boss

-

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’

Book reviews: ‘Hated by All the Right People: Tucker Carlson and the Unraveling of the Conservative Mind’ and ‘Football’Feature A right-wing pundit’s transformations and a closer look at one of America’s favorite sports