What is environmental justice?

Climate change disproportionately affects some groups more than others

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

"Environmental justice" is a buzzy phrase that often comes up when talking about climate-related issues. The Biden administration has even put forth funding for environmental justice in the Inflation Reduction Act. But what is environmental justice and why is it so important? Here's everything you need to know:

What is environmental justice?

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice as "the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies."

Essentially, the environmental justice movement acknowledges that environmental issues disproportionately affect some groups more than others. Those most affected tend to be low-income and communities of color, and the effects may or may not be intentional.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The modern environmental justice movement began in the 1980s in North Carolina during a dispute over the dumping of toxic waste near a predominately African American community. The term was cemented in the 1990s when a group of researchers drafted the "Principles of Environmental Justice" and the EPA officially defined the term and created an office dedicated to it, explains National Geographic.

What are environmental justice policies intended to address?

Environmental justice should be factored into every environmental decision. It can appear in both direct and indirect ways.

Pollution is an area in which environmental justice, specifically environmental racism, applies heavily. Environmental racism is the "intentional targeting of pollution in communities of color and low-income communities because they are less informed and they vote less," Peggy Shepard, co-founder of the nonprofit WE ACT for Environmental Justice, told CBS News. She stressed that marginalized communities often have less political power and tend to be located on cheaper land, leading to the locations becoming easy dumping grounds for industrial pollution.

Similarly, air pollution is distributed unevenly. Studies show Black residents absorb approximately 1.5 times the burden of air pollution of the population, National Geographic writes. This is largely due to historical "redlining," or policies that segregated minority communities, setting them in worse locations with less government investment.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Oil and natural gas drilling also often takes place in lower-income communities, making groundwater contamination and pollution a greater risk. From a policy standpoint, the debate over the Keystone pipeline largely brought environmental racism into the public eye since the installation of the pipeline would cut through multiple Indigenous lands in Canada and the U.S., infringing on their treaty rights.

Environmental justice also applies on an international scale. One of the main topics of COP27, or the U.N. Climate Summit, was "loss and damage." The U.N. acknowledged that some regions are facing the consequences of climate change faster and more severely than other countries; in turn, developed nations agreed to pay damages and reparations.

"Fighting for climate justice is a fight for everyone," Disha Ravi, founder of Fridays For Future India, said at the People's COP event in November, as reported by CNet. "It's a fight for the people we love, it's a fight for love itself, and that extends to people, the planet, and its inhabitants."

What is being done to further environmental justice?

The Biden administration announced $100 million in funding for environmental justice grants for "underserved and overburdened communities across the country." It is currently the largest environmental justice grant in history.

EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan called it a "key step that will help build strong partnerships with communities across the country," adding that it would "move us closer to realizing a more just and equitable future for all." Biden had made advancing environmental justice a key priority in his presidency, also adding it to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

However, historically money hasn't "made it to the places that need it the most," Vernice Miller-Travis, a veteran environmental justice activist and executive vice president at the Metropolitan Group, told The Washington Post. The IRA had to undergo some compromises in order for it to get passed, the Post goes on to explain: In order to get Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) to approve the bill, there needed to be more allowances for drilling leases, which is detrimental both for the climate and from an environmental justice standpoint. "That's always an issue, it's an ongoing issue," Miller-Travis adds.

The EPA has created a new Office of Environmental Justice with around 200 employees to evaluate projects to consider for funding. "The evaluation criteria has been specifically crafted to ensure the funding goes to low-income and disadvantaged communities," Regan said. The funding will be divided among nonprofit groups, state and local governments, tribal nations, and U.S. territories.

However, "if people of color and low-income people who are most affected by the issues are never in the rooms where the decisions are being made ... we are going to continue to have two different worlds," explains Shepard. "Two different realities do not make a unified country."

Devika Rao has worked as a staff writer at The Week since 2022, covering science, the environment, climate and business. She previously worked as a policy associate for a nonprofit organization advocating for environmental action from a business perspective.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Scientists are worried about amoebas

Scientists are worried about amoebasUnder the radar Small and very mighty

-

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticides

Europe’s apples are peppered with toxic pesticidesUnder the Radar Campaign groups say existing EU regulations don’t account for risk of ‘cocktail effect’

-

Climate change is getting under our skin

Climate change is getting under our skinUnder the radar Skin conditions are worsening because of warming temperatures

-

Kissing bug disease has a growing presence in the US

Kissing bug disease has a growing presence in the USThe explainer The disease has yielded a steady stream of cases in the last 10 years

-

Climate change is making us eat more sugar

Climate change is making us eat more sugarUnder the radar Sweets make the heat feel more manageable

-

Sloth fever shows no signs of slowing down

Sloth fever shows no signs of slowing downThe explainer The vector-borne illness is expanding its range

-

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?

Is that the buzzing sound of climate change worsening sleep apnea?Under the radar Catching diseases, not those ever-essential Zzs

-

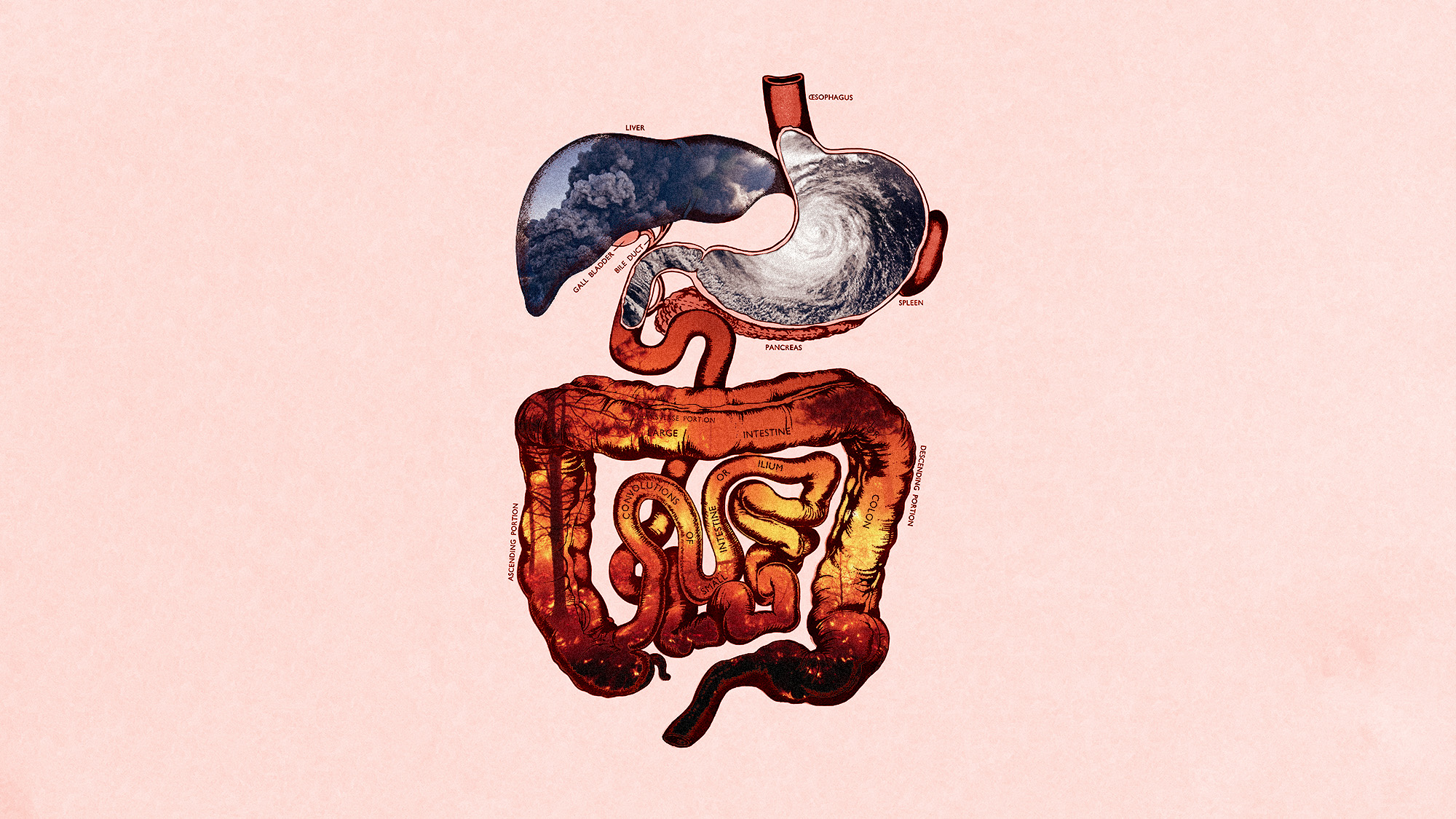

Climate change can impact our gut health

Climate change can impact our gut healthUnder the radar The gastrointestinal system is being gutted