The rise and rise of Center Parcs: ‘the paradise machine’

The holiday resort chain is up for sale, with a price tag somewhere north of £4bn. What is the secret of its success?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

It all began “with an idea”, according to the Center Parcs website: “the idea of bringing people and nature together”.

In 1968, Piet Derksen, a Dutch entrepreneur who owned a successful sporting goods chain, Sporthuis Centrum, set up De Lommerbergen, a holiday retreat in the woods near Reuver, close to the German border: initially just a series of tents in a field for his staff and customers.

But Derksen, who was also a devout conservative Catholic, soon grasped its potential, and conceived a vision of what he called “the villa in the forest”: an idyllic escape from city life. He commissioned the architect Jaap Bakema to make his vision a reality. Bakema designed a plan for a holiday village, with 30 simple, modernist bungalows nestled unobtrusively in the woodland, clustered around a “Center” that combined a swimming pool and other sports facilities. It provided a blueprint that is still replicated in Center Parcs today.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

How did the company grow?

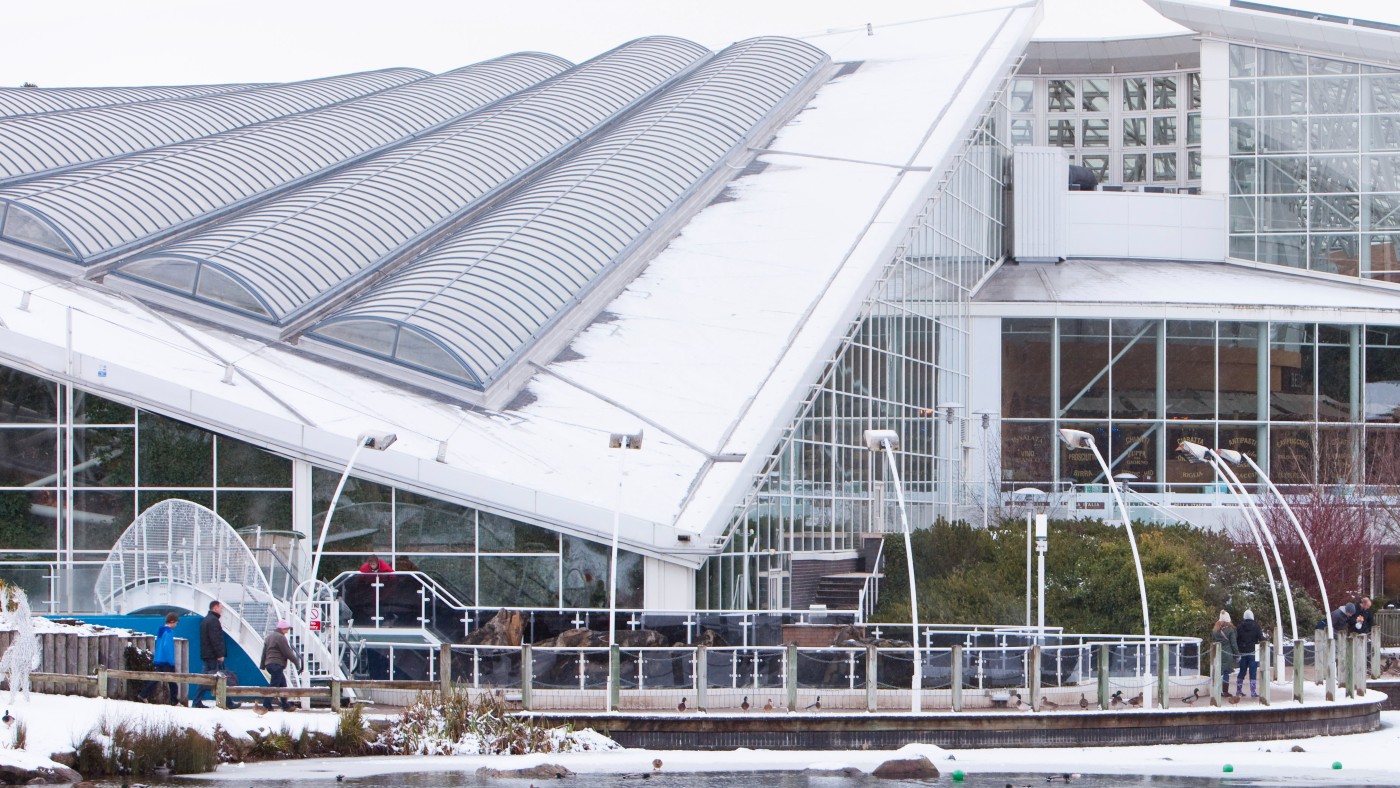

The concept was an instant hit, and in the 1970s five more villages were constructed. However, the winning formula was not really completed until 1980, when the “Aqua Mundo” was built at the De Eemhof village near Amsterdam: a glass dome containing a swimming pool complete with slides, wave machines and Jacuzzis, surrounded by lush tropical foliage. This was a big moment for the brand, writes the architect Tim O’Callaghan in his dissertation on what he calls “the paradise machine”, “cementing its ability to compete as a year-round destination, while also providing its first real architectural icon”. It was renamed Center Parcs in 1986. By 1987, when the first resort opened in the UK, in Sherwood Forest, there were Parcs in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands. Today there are 27 in mainland Europe, and six in the UK and Ireland. (The two companies have been separately owned since 2001; Derksen sold his shares in 1989.)

What’s the attraction?

The resorts present themselves as a safe, stress-free, traffic-free haven, offering a wide array of leisure activities, from swimming and cycling to falconry and fencing. Cars must be left at the entrance, but all resorts are conveniently close to a motorway or commuter hub. Guests still stay in “villas” or “treehouses” nestled in woodland. The British villages are all about 400 acres in size. They provide proximity to a manicured version of nature, but also access to artificial lakes, sports pitches, spas and restaurants; there are branches of Starbucks and Café Rouge on site. At the heart of all six UK and Irish sites sits a vast glazed “Subtropical Swimming Paradise”, heated to 29.5°C year-round – a geodesic dome in Sherwood Forest, a pyramid in Elveden Forest, a “giant clam” in Woburn Forest – providing weather-proof entertainment. Center Parcs has been described as a middle-class utopia, a Shangri-La for parents with young children, a “Boden Butlin’s”.

What about the downsides?

Center Parcs certainly has its detractors. “We all have our own idea of what hell looks like,” Kathryn Knight told the Daily Mail, “and mine is the domed Subtropical Swimming Paradise at Center Parcs in Woburn Forest, on a Saturday morning.” The Parcs have been described by critics as like living in a giant Ikea or an open prison (they all have perimeter fences to keep children in and unwanted visitors out). The identikit lodges, some complain, are soulless and give the place a “Truman Show”-like feel; the food, some say, is expensive and mediocre. Mainly, though, it’s the prices that people object to: in school holidays, these will often exceed an all-inclusive holiday abroad. A four-night break for a family of four in August costs between £1,449 and £4,199 (for an “exclusive lodge”). On top of that, guests have to shell out for food (the lodges are self-catering) and though swimming is free, activities cost extra: from hiring bicycles to teddy bear making (£25.50 for ten minutes), table tennis (up to £8.75 for 30 mins) and “quad bike safari” (up to £47.50 an hour).

How popular are they?

Despite the high prices, and the odd PR disaster (the business tried to banish guests for 24 hours “as a mark of respect” over The Queen’s funeral last year, though it later U-turned on the decision), Center Parcs are still hugely popular. The British and Irish resorts attract more than two million visitors each year, and they are effectively full, all the time: the annual occupancy rate is over 97%. More than half of visitors return within five years. Since Covid, Center Parcs have benefitted from the boom in “staycations”, and during the cost-of-living crisis, they seem relatively affordable: they offer budget options, and also appeal to wealthier customers trading down from foreign trips.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

How big is the business?

The UK and Irish business is being put up for sale by its owners, the global real estate group Brookfield Property Partners. Although no official statement has been issued, the price tag is reported to be between £4bn and £5bn – about double the £2.4bn Brookfield bought it for in 2015. If that seems exorbitant, the company is a giant cash machine: it booked revenue of £426.6m between April and December 2022, up 18% on its pre-pandemic figures. It made pre-tax profits of £66.2m for the year to April 2022.

What does the future hold?

Center Parcs is hoping to build another village in the UK (though plans for another site in West Sussex, near Gatwick, were rejected on environmental grounds). And whoever owns it, Europe’s answer to Disneyland, offering a safe, sanitised version of nature, looks likely to go from strength to strength. The secret of the brand’s success is that people will pay through the nose for child-centred holidays. As customers say: “If the kids are happy, we’re happy.”

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’

Book reviews: ‘Bonfire of the Murdochs’ and ‘The Typewriter and the Guillotine’Feature New insights into the Murdoch family’s turmoil and a renowned journalist’s time in pre-World War II Paris

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Currencies: Why Trump wants a weak dollar

Currencies: Why Trump wants a weak dollarFeature The dollar has fallen 12% since Trump took office

-

Elon Musk’s starry mega-merger

Elon Musk’s starry mega-mergerTalking Point SpaceX founder is promising investors a rocket trip to the future – and a sprawling conglomerate to boot

-

TikTok: New owners, same risks

TikTok: New owners, same risksFeature What are Larry Ellison’s plans for TikTok US?

-

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?

Will SpaceX, OpenAI and Anthropic make 2026 the year of mega tech listings?In Depth SpaceX float may come as soon as this year, and would be the largest IPO in history

-

Leadership: A conspicuous silence from CEOs

Leadership: A conspicuous silence from CEOsFeature CEOs were more vocal during Trump’s first term

-

Ryanair/SpaceX: could Musk really buy the airline?

Ryanair/SpaceX: could Musk really buy the airline?Talking Point Irish budget carrier has become embroiled in unlikely feud with the world’s wealthiest man

-

Powell: The Fed’s last hope?

Powell: The Fed’s last hope?Feature Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell fights back against President Trump's claims

-

Taxes: It’s California vs. the billionaires

Taxes: It’s California vs. the billionairesFeature Larry Page and Peter Thiel may take their wealth elsewhere