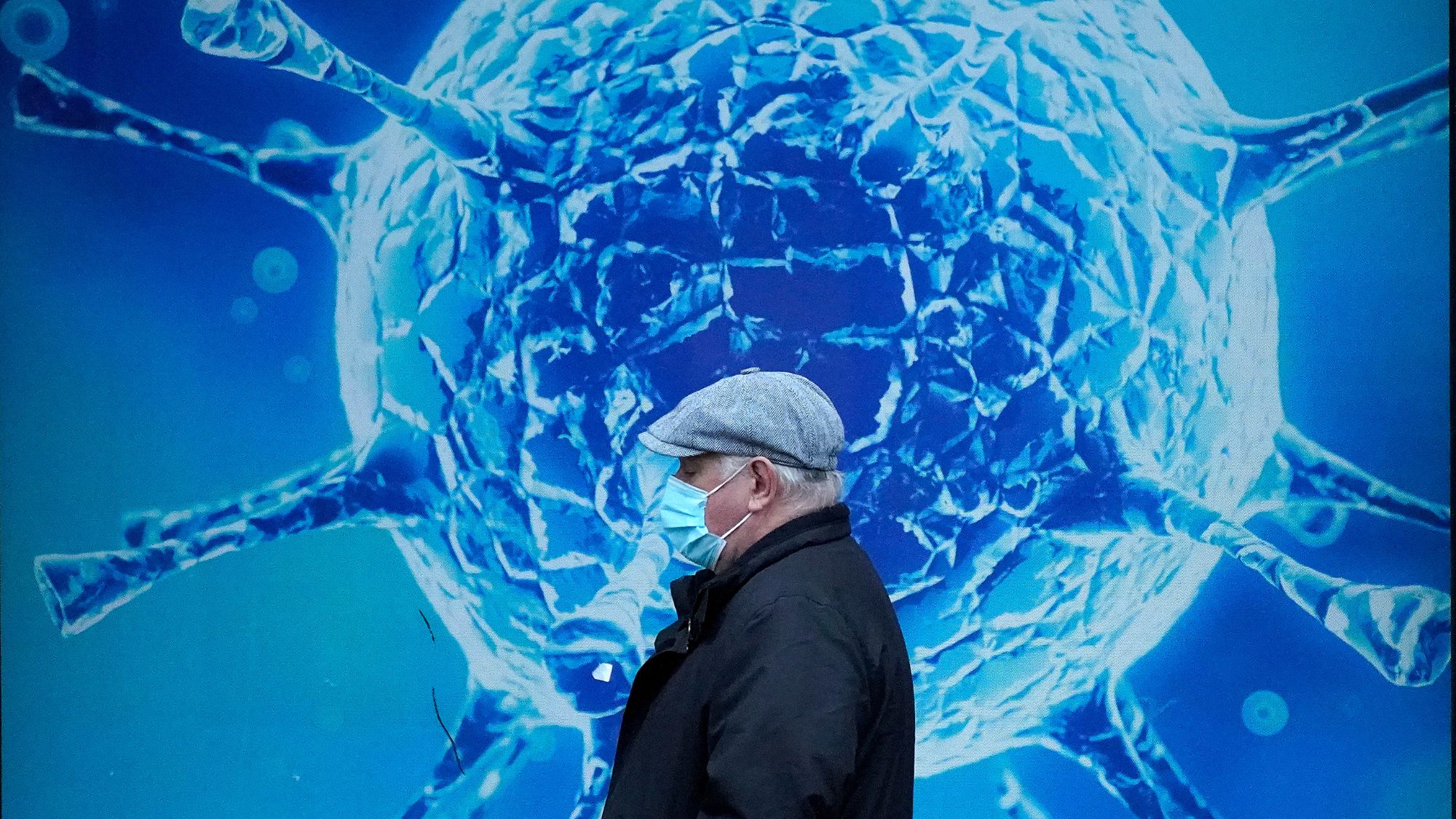

Coronavirus: the conspiracy theories

Misinformation has potential to be just as damaging as the outbreak itself, say psychology academics

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Daniel Jolley, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Northumbria University, Newcastle, and Pia Lamberty, PhD Researcher in Social and Legal Psychology, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, look at how coronavirus is becoming a breeding ground for conspiracy theories in an article originally written for The Conversation.

The novel coronavirus continues to spread around the world, with new cases being reported all the time. Spreading just as fast, it seems, are conspiracy theories that claim powerful actors are plotting something sinister to do with the virus. Our research into medical conspiracy theories shows that this has the potential to be just as dangerous for societies as the outbreak itself.

One conspiracy theory proposes that the coronavirus is actually a bio-weapon engineered by the CIA as a way to wage war on China. Others are convinced that the UK and US governments introduced the coronavirus as a way to make money from a potential vaccine.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although many of these conspiracy theories seem far-fetched, the belief that evil powers are pursuing a secret plan is widespread in every society. Often these relate to health. A large 2019 YouGov poll found 16% of respondents in Spain believe that HIV was created and spread around the world on purpose by a secret group or organisation. And 27% of French and 12% of British respondents were convinced that “the truth about the harmful effects of vaccines is being deliberately hidden from the public”.

The spread of fake news and conspiracy theories around the coronavirus is such a significant problem that the World Health Organisation (WHO) has created a “myth busters” webpage to try and tackle them.

Spread of conspiracy theories

Research shows that conspiracy theories have a tendency to arise in relation to moments of crisis in society – like terrorist attacks, rapid political changes or economic crisis. Conspiracy theories bloom in periods of uncertainty and threat, where we seek to make sense of a chaotic world. These are the same conditions produced by virus outbreaks, which explains the spread of conspiracy theories in relation to coronavirus.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Similar conditions occurred with the 2015-16 outbreak of Zika virus. Zika conspiracy theories proposed that the virus was a biological weapon rather than a natural occurrence. Research examining comments on Reddit during the Zika virus outbreak found conspiracy talk emerged as a way for people to cope with the extreme uncertainty they felt over Zika.

Trust in the recommendations from health professionals and organisations is an important resource for dealing with a health crisis. But people who believe in conspiracy theories generally do not trust groups they perceive as powerful, including managers, politicians and drug companies. If people do not trust, they are less likely to follow medical advice.

Researchers have shown that medical conspiracy theories have the power to increase distrust in medical authorities, which can impact people’s willingness to protect themselves. People who endorse medical conspiracy theories are less likely to get vaccinated or use antibiotics and are more likely to take herbal supplements or vitamins. Plus, they are more likely to say they would trust medical advice from nonprofessionals such as friends and family.

Severe consequences

In light of these results, people who endorse conspiracy theories about the coronavirus may be less likely to follow health advice like frequent hand-cleaning with alcohol-based hand rub or soap, or self-isolating after visiting at-risk areas.

Instead, these people may be more likely to have negative attitudes towards prevention behaviour or use dangerous alternatives as treatments. This would increase the likelihood of the virus spreading and put more people in danger.

Already, we can see “alternative healing approaches” to coronavirus cropping up – some of them very dangerous. Promoters of the popular QAnon conspiracy theory, for example, have said the coronavirus was planned by the so-called “deep state” and claimed the virus can be warded off by drinking bleach.

The spread of medical conspiracy theories can also have severe consequences for other sections of society. For example, during the Black Death in Europe, Jews were scapegoated as responsible for the pandemic. These conspiracy theories led to violent attacks and massacres of Jewish communities all over Europe. The outbreak of the coronavirus has led to a worldwide increase in racist attacks targeted towards people perceived as East Asian.

It is possible to intervene and halt the spread of conspiracy theories, however. Research shows that campaigns promoting counterarguments to medical conspiracy theories are likely to have some success in rectifying conspiracy beliefs. Games such as Bad News, in which people can take the role of a fake news producer, have been shown to improve people’s ability to spot and resist misinformation.

Conspiracy theories can be very harmful for society. Not only can they influence people’s health choices, they can interfere with how different groups relate to each other and increase hostility and violence towards those who are perceived to be “conspiring”. So as well as acting to combat the spread of the coronavirus, governments should also act to stop misinformation and conspiracy theories relating to the virus from getting out of hand.

Daniel Jolley, Senior Lecturer in Psychology, Northumbria University, Newcastle and Pia Lamberty, PhD Researcher in Social and Legal Psychology, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the rise

The new Stratus Covid strain – and why it’s on the riseThe Explainer ‘No evidence’ new variant is more dangerous or that vaccines won’t work against it, say UK health experts

-

Poor sleep may make you more prone to believing conspiracy theories

Poor sleep may make you more prone to believing conspiracy theoriesUnder the radar Catch z's for society

-

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variants

Covid-19: what to know about UK's new Juno and Pirola variantsin depth Rapidly spreading new JN.1 strain is 'yet another reminder that the pandemic is far from over'

-

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid science

Vallance diaries: Boris Johnson 'bamboozled' by Covid scienceSpeed Read Then PM struggled to get his head around key terms and stats, chief scientific advisor claims

-

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023

Good health news: seven surprising medical discoveries made in 2023In Depth A fingerprint test for cancer, a menopause patch and the shocking impacts of body odour are just a few of the developments made this year

-

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?

How serious a threat is new Omicron Covid variant XBB.1.5?feature The so-called Kraken strain can bind more tightly to ‘the doors the virus uses to enter our cells’

-

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?

Will new ‘bivalent booster’ head off a winter Covid wave?Today's Big Question The jab combines the original form of the Covid vaccine with a version tailored for Omicron

-

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?

Can North Korea control a major Covid outbreak?feature Notoriously secretive state ‘on verge of catastrophe’