Lucy Letby: a miscarriage of justice?

Since Letby's conviction for killing seven babies at a neonatal unit, experts have expressed grave doubts about the case

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

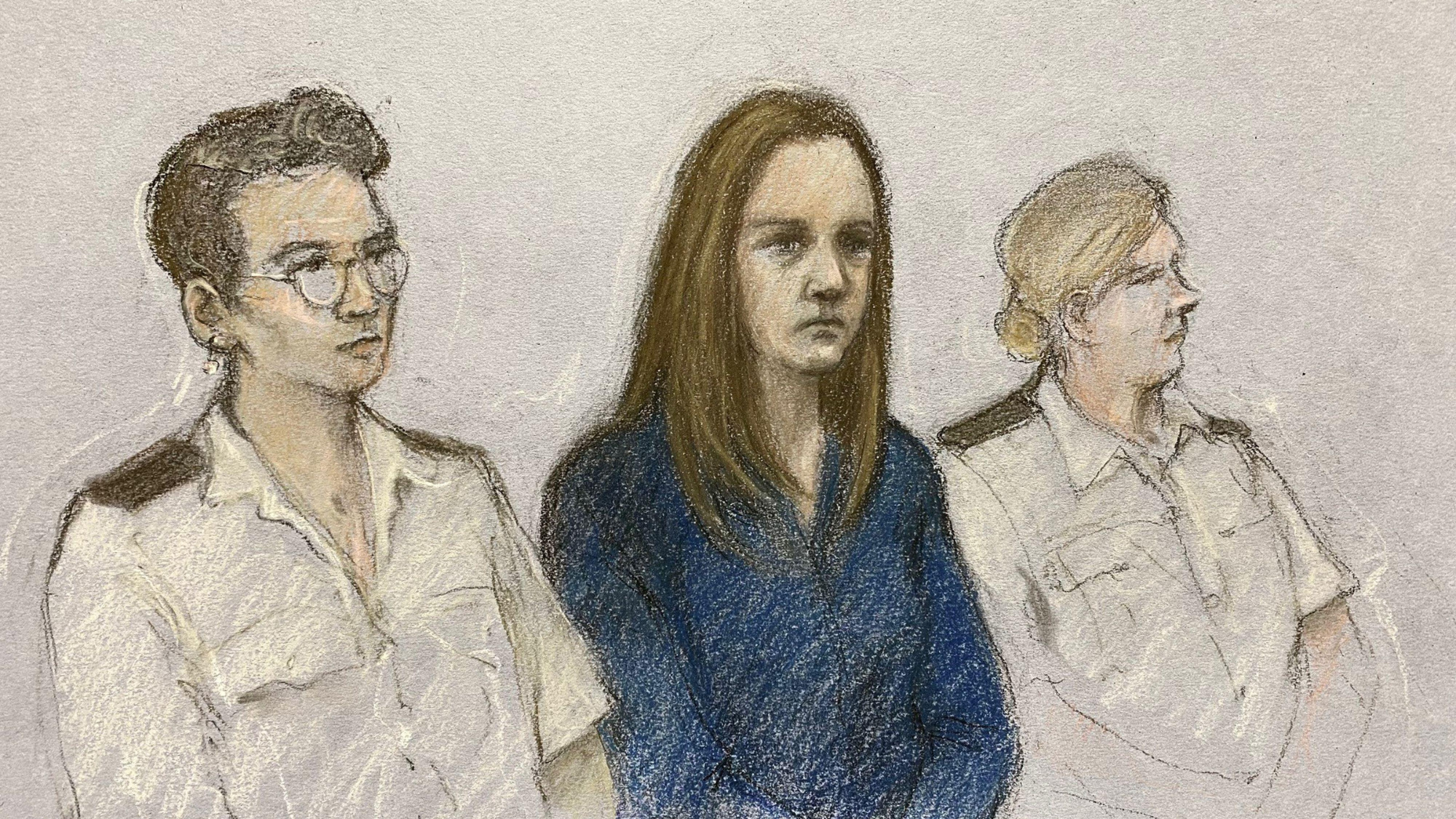

In early July, Lucy Letby, a former nurse now aged 34, was convicted of attempted murder. It was a retrial on a charge not decided in the main trial that ran from October 2022 to August 2023.

In total, Letby was convicted of murdering seven very young babies and attempting to murder seven others at a neonatal unit at the Countess of Chester (CoC) Hospital in Cheshire in 2015 and 2016. Her methods, the court concluded, included injecting premature infants with air or insulin, overfeeding them, and harming them with medical tools.

Sentenced to life imprisonment on a "whole life order", she is regarded as the worst child serial killer in British history. But now that the trials are over, the media is able to report in full on a chorus of doubts about the quality of the evidence against her.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What evidence was there against her?

The case against Letby was circumstantial: nobody saw her harming a baby, and there was no incontrovertible evidence that she did so. It rested on various strands, notably, statistical evidence about her shift patterns and how they coincided with children's deaths and crises; expert medical opinion on the possible causes of those; eyewitness testimony from colleagues who became suspicious of her behaviour; and written "confessions" – a series of Post-It notes on which she had written fragmentary phrases such as "help", "not good enough", "I killed them on purpose because I'm not good enough to care for them", and "I AM EVIL I DID THIS". Questions have been raised, in particular, about the statistical and the medical evidence.

What issues have been raised over the statistics?

From June 2015 to June 2016, the number of deaths at the CoC neonatal unit surged, going from an average of four per year to several times that. A chart presented to the jury showed 39 nurses' shifts plotted against 25 "suspicious events", seven deaths and 17 sudden "collapses": Letby, the prosecuting barrister pointed out, was on duty every time. She was the "one constant presence"; after she was taken off the ward, deaths reduced sharply.

However, the jury was not told about at least six other deaths at the unit, and scores of collapses, in the same period. This is a clear misuse of statistics, which has been widely condemned. Besides, there's a simpler explanation for the spike in deaths: the CoC neonatal unit was experiencing profound and well-attested problems due to understaffing and poor clinical practice. It was downgraded in summer 2016, so it took fewer high-risk cases – after which, unsurprisingly, deaths dropped.

The first suspicions about Letby came when two doctors at the Countess of Chester, discussing the sudden spate of deaths, said to each other: "It's always Lucy, isn't it?" They made the first diagram plotting shift patterns against suspicious incidents, a version of which was shown repeatedly to the jury, and featured prominently in media coverage.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Many statisticians say that the jury should never have seen it. It exhibits what they call the "Texas sharpshooter fallacy", based on a fable about a gunman who fires a series of bullets into a barn, then draws a bullseye around the cluster where most bullets landed. If you draw a circle around any artificially isolated dataset, it can be made to look like a pattern.

In this case, the selection was very artificial. It excluded six to ten other deaths (the hospital has given inconsistent figures) and tens, perhaps hundreds, of non-fatal incidents; Letby also took on more shifts than most of her colleagues did. "All the shift chart shows is that when Letby was on duty, Letby was on duty," said John O'Quigley, professor of statistics at UCL. Similarly flawed reasoning was used to convict Lucia de Berk, a nurse, in the Netherlands, in what is now seen as one of the country's worst-ever miscarriages of justice.

And the medical evidence?

Many doctors have argued that the prosecution case was based on implausible and inaccurate evidence. One of the key charges was that Letby injected air into babies' veins, blocking blood vessels and causing death. Dr Shoo Lee, author of a medical paper on "air embolisms" in newborn babies, has expressed strong doubts about the way that they had been diagnosed in this case.

Letby was also accused of injecting air into babies' stomachs using a nasogastric tube, causing collapse and death. Eight separate expert clinicians who spoke to The Guardian took issue with this theory, describing it as "rubbish", "implausible" and "fantastical". It was also charged that Letby tried to kill babies by administering synthetic insulin; among others, Professor Alan Wayne Jones, one of Europe's leading experts on toxicology and insulin, has argued that the tests used to reach this conclusion were fundamentally misinterpreted.

So why was the jury convinced?

Presumably, it was convinced by the evidence of the prosecution's medical experts, particularly the lead expert, Dr Dewi Evans, a retired consultant paediatrician. The expert for the defence, Dr Michael Hall, took an entirely different view of the case. In Hall's view, Evans "exaggerated" how well all the babies who died were, and constructed theories to suit the prosecution. It is not clear, in Hall's view, that any of the deaths were in fact murders: six out of seven of the children had postmortem exams at Alder Hey Children's Hospital in Liverpool, and no concerning evidence was discovered.

Strangely, though, Hall was never called by Letby's lawyers to challenge Evans's evidence; Hall, and others, were very troubled by this. The defence barrister, Benjamin Myers KC, did attempt to have Evans's evidence declared inadmissible, on the grounds that it didn't meet minimum standards, but the judge rejected the application.

But what about Letby's "confessions"?

The defence argued that the apparent confessions were not evidence of a guilty conscience, but of a young woman, under terrible pressure from false accusations, sliding into a breakdown. "That's how I was being made to feel," she told police during questioning. Throughout, Letby denied committing any crime.

Should her conviction be overturned?

Many would say not: the evidence was, after all, examined in detail for ten months; the defence had every chance to make its case; and the jury found Letby guilty. Her lawyers have appealed since, trying again to get Evans's evidence declared inadmissible, and to undermine his air embolism theory. The Court of Appeal rejected this, on the grounds that Evans's evidence was at times contentious, but not so tenuous as to need expunging.

In appeals, defence lawyers are not allowed a "second bite at the cherry": they can't go back through the evidence and make a better case than they did the first time, otherwise trials would be endlessly appealed. Lawyers have to show that new evidence has emerged, or that the judge made a legal mistake. The Court of Appeal found that neither condition was met. Now Letby's only hope is the Criminal Cases Review Commission, which can look anew at potential miscarriages of justice.