Emily Kam Kngwarray: a 'fantastic' exhibition

The Tate Modern showcases a gripping tribute to a 'titan of Australian art'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

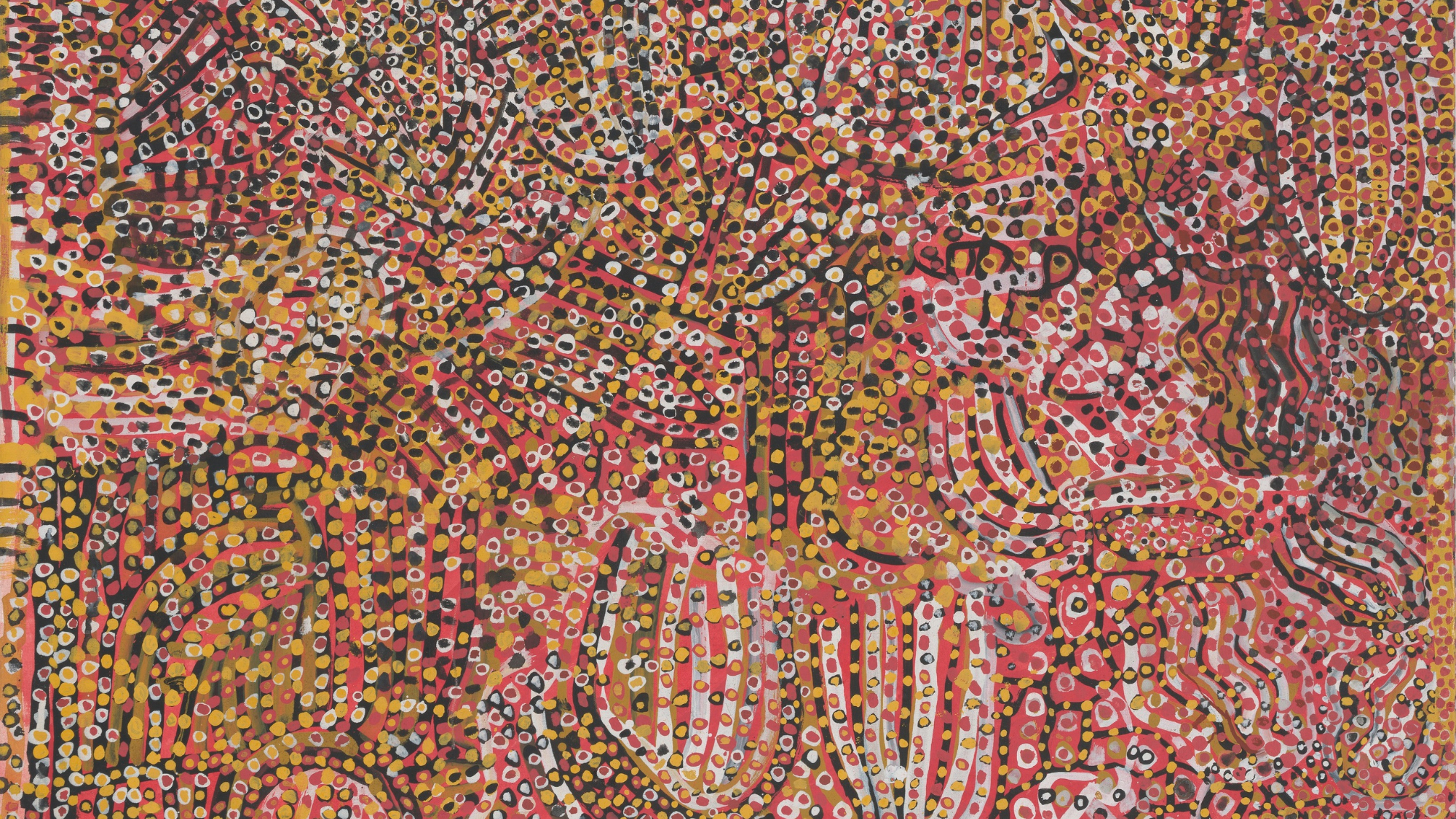

You may have never heard of her, but in Australia the Aboriginal artist Emily Kam Kngwarray is a household name, said Nancy Durrant in The Times. An elder of the Anmatyerr communities of the sparsely populated Northern Territory, "Kam", as she was known, had produced around 3,000 paintings by the time of her death in 1996, aged around 80 (her birthdate is "hazy").

Remarkably, all of them were made in her final decade. They are pictures that teem with life, patterns of dashes, or dots, in colour configurations that give the impression of individual marks dancing before the eyes. To us, they might look abstract – some bear a resemblance to the work of, say, Jackson Pollock – but everything she made was "firmly rooted in her ancestral lands", "an extension of cultural traditions specific to her people".

While recognition came late, it was well deserved: her works have "a vitality, a dynamism, a beauty, depth and complexity that sets them apart". This is only the first major exhibition of her work in Europe. It brings together a "fantastic" selection of paintings, accompanied by archival videos of the artist at work; the curators have done a great job at filling in the cultural background. This is a gripping and long-overdue tribute to a "titan of Australian art".

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Kngwarray spent much of her life doing agricultural and menial jobs, said Adrian Searle in The Guardian. She barely spoke English and generally worked for "rations", rather than money. Although she made batik textile pieces earlier in her life – some of which we see here – it was only when an Aboriginal organisation began distributing painting materials in the 1980s that she started to create the work for which she became famous.

While her canvases are accessible, "the imagery, motifs, iconography, and even spatial sense of Kngwarray's work come directly from her indigenous Anmatyerr culture": from communal body painting, sketches made in sand at ceremonies, ancestral stories. She was "hesitant about revealing" these meanings. You can, though, discern recurring features: footprints of emus in the sand; the vine of the pencil yam, a staple and sacred crop in Anmatyerr culture, from which the artist's name, Kam, derives.

Not everything here is great, said Alastair Sooke in The Daily Telegraph. Early canvases are so similar in style as to look "interchangeable": some resemble "star charts", others "aerial shots of arid landscapes". The Tate, however, treats them all with rather patronising reverence. In its second half, though, the show suddenly "takes flight": 1993's 22-panel painting "Alhalker Suite" is a work of "inspired, unbridled exuberance", formed of "blotches of wildflower-pink and clear-sky-blue", which are interspersed with "thick, gestural lines and squiggles". "The final room, filled with powerful compositions produced shortly before Kngwarray's death in 1996, burning bright against black backgrounds, is a knockout."

Tate Modern, London SE1 . Until 11 January 2026

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Political cartoons for February 6

Political cartoons for February 6Cartoons Friday’s political cartoons include Washington Post layoffs, no surprises, and more

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentary

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentaryTalking Point The film has played to largely empty cinemas, but it does have one fan

-

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’

Nouvelle Vague: ‘a film of great passion’The Week Recommends Richard Linklater’s homage to the French New Wave

-

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel Universe

Wonder Man: a ‘rare morsel of actual substance’ in the Marvel UniverseThe Week Recommends A Marvel series that hasn’t much to do with superheroes

-

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcom

Is This Thing On? – Bradley Cooper’s ‘likeable and spirited’ romcomThe Week Recommends ‘Refreshingly informal’ film based on the life of British comedian John Bishop

-

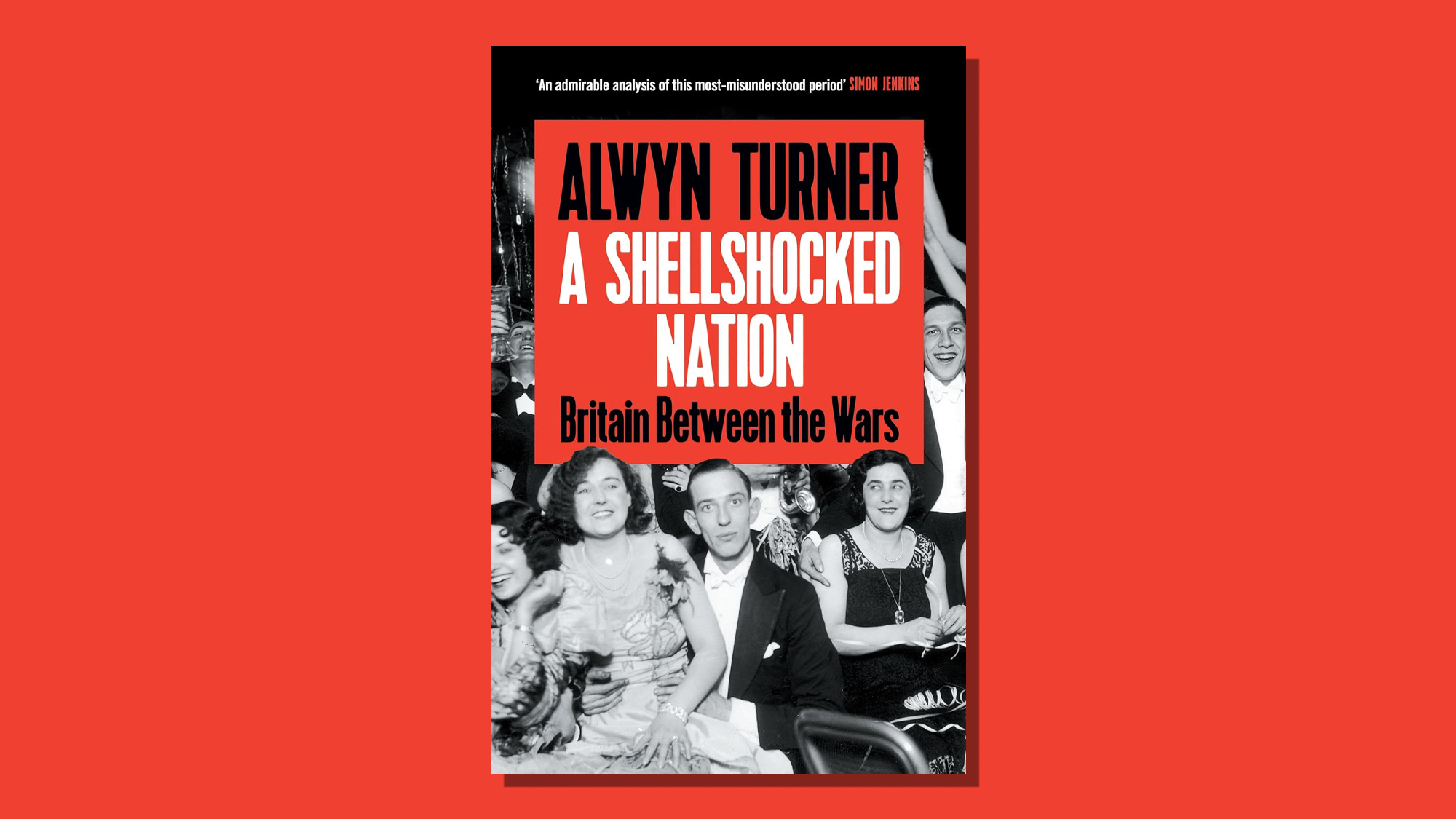

A Shellshocked Nation: Britain Between the Wars – history at its most ‘human’

A Shellshocked Nation: Britain Between the Wars – history at its most ‘human’The Week Recommends Alwyn Turner’s ‘witty and wide-ranging’ account of the interwar years