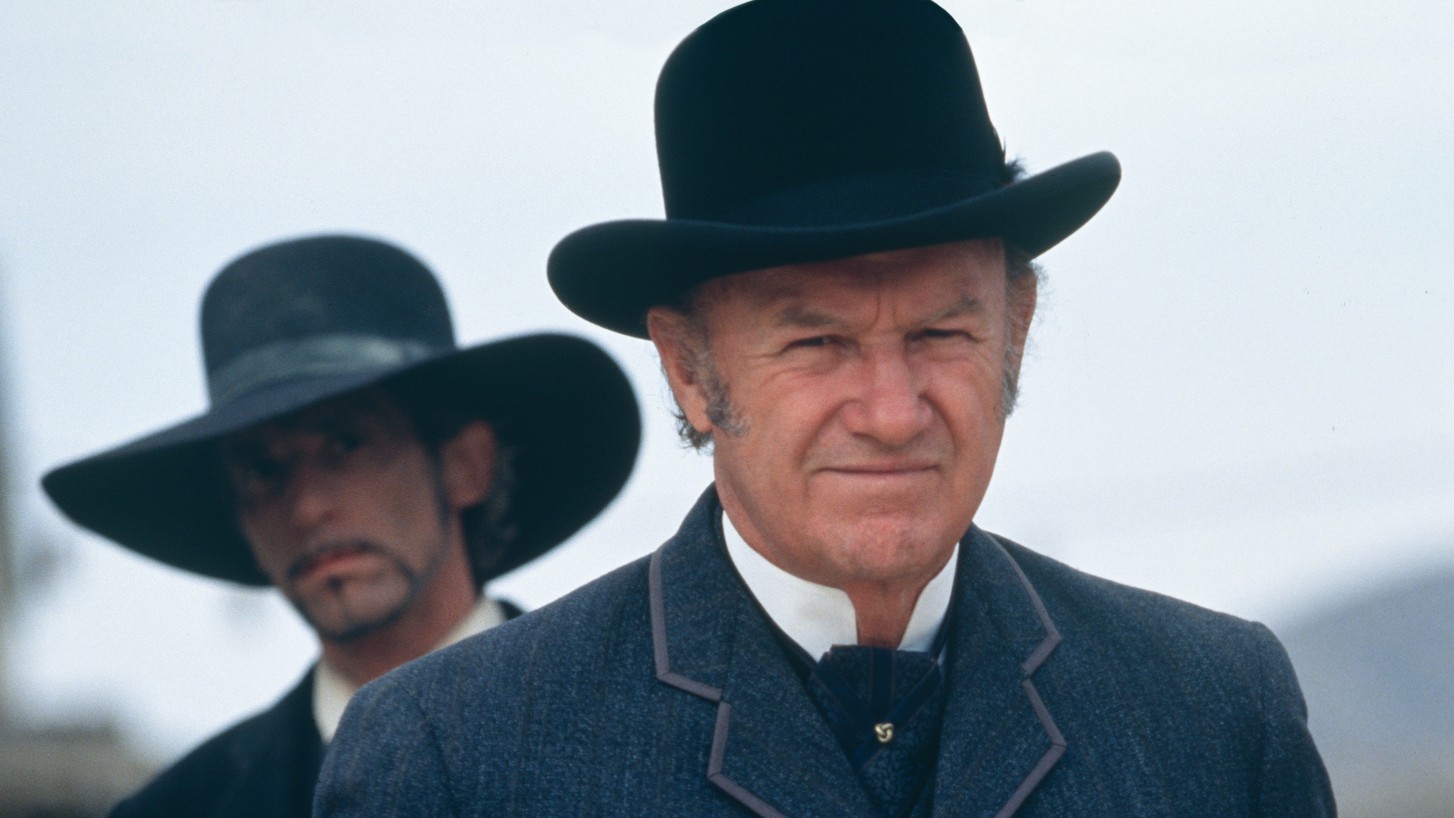

Gene Hackman: the death of a Hollywood legend

The French Connection actor had an extraordinary gift for making characters believable

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

With a distinctive gravelly voice and magnetic screen presence, Gene Hackman, who has died aged 95, was one of the great film actors of the late 20th century. Yet few have had such an unlikely route to stardom, said The Guardian. His family background was fraught; he had no early contact with showbusiness; and his looks were, at best, "homely" – he joked that he had the face of "your everyday mine worker", and he always looked middle-aged.

He only settled on a career in acting when he was in his 20s, and was in his late 30s by the time he got his breakthrough as the elder brother in "Bonnie and Clyde", in 1967, which garnered him an Oscar nomination. Four years later, he was cast as Popeye Doyle in "The French Connection". It won him the first of his two Oscars, and made him a household name.

An extraordinary gift

For the next three decades, Hackman was one of Hollywood's most respected and prolific character actors. He was in a lot of bad films: for a few years, he admitted, he had worked mainly for money, having run up a large unpaid tax bill. But whether he was the comically villainous Lex Luthor in "Superman" (1978), the world-weary FBI agent in "Mississippi Burning" (1988), or the sadistic sheriff in "Unforgiven" (1992), for which he won his second Oscar, he was rarely less than excellent, said The New York Times. An actor who seemed to inhabit his roles, rather than merely play them, he had an extraordinary gift for making characters believable. As the writer Jeremy McCarter put it: "In his performances, as in life, the good guys aren't always nice guys, and the villains have charm."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Although often cast as tough guys, Hackman insisted that he was not one himself: he thought of himself as sensitive, and took his acting extremely seriously. But he had, he said, anger in him that he was able to "touch on" to create a sense of danger, which may have been a legacy of his unsettled childhood.

Eugene Hackman was born in California in 1930 and raised in Illinois. His mother was a waitress; his father, a violent man, struggled to find work during the Depression, and abandoned the family when Gene was 13. Years later, Hackman recalled that as his father drove away for the last time, he gave him a wave as he passed, as if to say "OK, it's all yours. You're on your own now, kiddo." "I hadn't realised how much one small gesture can mean," Hackman said. "Maybe that's why I became an actor."

After that, he got into fights, left school early and, aged 16, lied about his age to join the Marine Corps. He served mainly in the Far East. But in 1952, he was invalided out after an accident, and had to find a new career. He briefly studied journalism, then moved into TV production. Finally, encouraged by his wife, Faye Maltese, he decided to pursue a long-held ambition to act, and enrolled at the Pasadena Playhouse in California, where he was far older than most of the cohort, but struck up a lasting friendship with fellow student Dustin Hoffman. Their classmates voted them both "least likely to succeed", and for a time it looked as though they might have been right about Hackman. Returning to New York, he took various dead-end jobs to support his family (he eventually had three children) while trying and failing to get a break in acting.

A relentless worker

Hackman refused, however, to give up, and eventually he was offered a bit part in a play off Broadway. He made his film debut in 1961. In the years after "The French Connection", Hackman found his fame hard to handle; and he was troubled by its impact on his family.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

He was also impatient with aspects of the film business: he hated having to have lunch meetings with executives and being fussed over by make-up artists, and detested being given line notes. For years, he worked relentlessly, but at other times he took career breaks to pursue other interests: he flew biplanes; he was an accomplished painter and the co-author of three historical novels.

His later roles ranged from a high-school sports coach in "Hoosiers" to a murderous president in "Absolute Power", and a reclusive surveillance expert in "Enemy of the State" – an action thriller that was, in part, an homage to Francis Ford Coppola's 1974 drama "The Conversation", which had provided Hackman with one of the greatest roles of his career. He made his last film in 2004.

His first marriage had struggled under the pressure of his work and ended in 1986. In 1991, he married Betsy Arakawa, a classical musician. Both were found dead in their home in Santa Fe last week; the cause of their death is as yet unclear. She was 65.

-

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peace

Buddhist monks’ US walk for peaceUnder the Radar Crowds have turned out on the roads from California to Washington and ‘millions are finding hope in their journey’

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’

How to navigate dating apps to find ‘the one’The Week Recommends Put an end to endless swiping and make real romantic connections

-

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’

Catherine O'Hara: The madcap actress who sparkled on ‘SCTV’ and ‘Schitt’s Creek’Feature O'Hara cracked up audiences for more than 50 years

-

6 gorgeous homes in warm climes

6 gorgeous homes in warm climesFeature Featuring a Spanish Revival in Tucson and Richard Neutra-designed modernist home in Los Angeles

-

Touring the vineyards of southern Bolivia

Touring the vineyards of southern BoliviaThe Week Recommends Strongly reminiscent of Andalusia, these vineyards cut deep into the country’s southwest

-

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibition

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency – an ‘engrossing’ exhibitionThe Week Recommends All 126 images from the American photographer’s ‘influential’ photobook have come to the UK for the first time

-

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classic

American Psycho: a ‘hypnotic’ adaptation of the Bret Easton Ellis classicThe Week Recommends Rupert Goold’s musical has ‘demonic razzle dazzle’ in spades

-

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walks

Properties of the week: houses near spectacular coastal walksThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in Cornwall, Devon and Northumberland

-

Josh D’Amaro: the theme park guru taking over Disney

Josh D’Amaro: the theme park guru taking over DisneyIn the Spotlight D’Amaro has worked for the Mouse House for 27 years

-

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentary

Melania: an ‘ice-cold’ documentaryTalking Point The film has played to largely empty cinemas, but it does have one fan