How a classic 1951 film understood journalism better than we do now

Why is the news is so bad? Watch 'Ace in the Hole.'

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Pick something, anything, you hate in the world of journalism: sensationalism; focusing on unimportant stories; not covering important stories; left-wing bias; right-wing bias; saying that real news is "fake news"; saying that "fake news" is real news; Gawker; Gawker getting sued into oblivion; mixing the worst imaginable ads into real stories — there are a million other things. It would be nice to blame it all on opportunists who exploit whatever they can to promote themselves and make money and be done with it.

But why are the opportunities there to begin with?

The 1951 movie Ace in the Hole, co-written and directed by Billy Wilder, understood that whatever gripe you chose from the list above, it didn't arise out of a vaccum — those responsible for it are responding to incentives. In the movie, Chuck Tatum, a hard-drinking reporter played by Kirk Douglas, has been fired from almost every big-city newspaper and finds himself in Albuquerque, where he gets a job on a paper. En route to an assignment one day, he discovers Leo Minosa (Richard Benedict), who's become trapped underground by a cave-in while he was looking for Indian artifacts. With the help of the corrupt local sheriff, Tatum has the excavation team use a drill that will take a week to get Minosa out instead of shoring up the walls, which would take a day, and prevents other reporters from speaking to Minosa. He then plans to alter the facts as necessary and use his week of exclusive copy to write such a massive story that it secure the sheriff's re-election and get his old job in New York back.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

Needless to say, it isn't a movie that paints journalism and its practitioners in a positive light. But it understands why Tatum keeps getting second chances and why he does, eventually, get his New York job back. He gives the people what they want — and they enthusiastically pay for it.

Tatum looks bad, but the people who consume the news look even worse. His reporting causes thousands of people to gather at the mountain Minosa is buried under, creating a carnivalesque atmosphere. Ace in the Hole spends the most time with one representative of the mob, an insurance salesman from Gallup named Al Federber. He read Tatum's reporting and decides to take a detour on his family vacation to see the place, and when he gets there he has his wife wake their kids up, telling her, "they should see this. This is very instructive." I can hardly fathom how; will he tell them that, contrary to what they might think, it's actually bad to be trapped in a cave-in?

Jokes aside, the comment reveals a lot about Federber's perspective on the news. To him, the site is instructive, and he found Tatum's news story instructive as well. But Tatum's story is not instructive, and whether it contains anything true — besides the part about a man being stuck underground — is doubtful. Tatum has invented a heartbroken wife (Minosa's wife actually loathes him and wants to leave him) and an Indian curse (his inspiration seems to be similar talk of curses when King Tut's tomb was discovered). If the public wants heartbroken wives and Indian curses, they can have them, and they can flatter themselves that, since this is the news, it's very instructive and educational. Tatum is a man out to appeal to the public, and he's happy to play to the desire to seem informed and knowledgeable and use the prestige of the news to let the masses avoid having to acknowledge its taste for sentimental pablum and cheap sensationalism.

Federber and his family stick around, and we see them again when the host of a radio show that has set up on location solicits him for some man-on-the-street commentary. He first uses his time on the air to suggest that, contrary to a claim made on the radio show earlier, he and his family were the first people there. He then opportunistically pivots to expressing his hope that Minosa had bought insurance and starts talking about a policy his company offers when the host cuts him off. But he is unfazed and starts handing out his business card to the people around him.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Federber and Tatum are two sides of the same coin. Both want to promote their brands (as we would say) by making sure everyone knows they were the first to arrive on the scene, and both seize the opportunity presented to them to make some money and advance their careers. The reason, according to Wilder, that Tatum can flourish is a symbiotic relationship with a nation of Federbers who act like Tatum, think like Tatum, understand the news the way Tatum does, and eagerly consume the news that Tatum produces. And Federber can pretend that he's doing something good and helpful by reading that news, even if it's designed to appeal to his worst instincts. After all, it's the news; it can't be bad.

Some things haven't changed about journalism since 1951, some have — but in 2022, when journalists talk openly about the importance of their brands and Americans carefully curate their appearance to the world on social media and consume increasingly targeted news, it's hard to deny that Wilder had a point. I can imagine a remake today, in which Tatum gets into drunken Twitter beefs with anyone questioning his handling of the story and Federber annoys his cousins on Facebook with an avalanche of unconventionally capitalized posts about The Most Important Story Ever, Leo Minosa, and how vital it is to read the news (by which he means clicking on links he sees on his feed).

I am begging any producers reading not to make this; it would be awful. But would it be wrong?

Steve Larkin is a writer from the state of Maine. His writing has appeared in The Week, the Catholic Herald, and other publications.

-

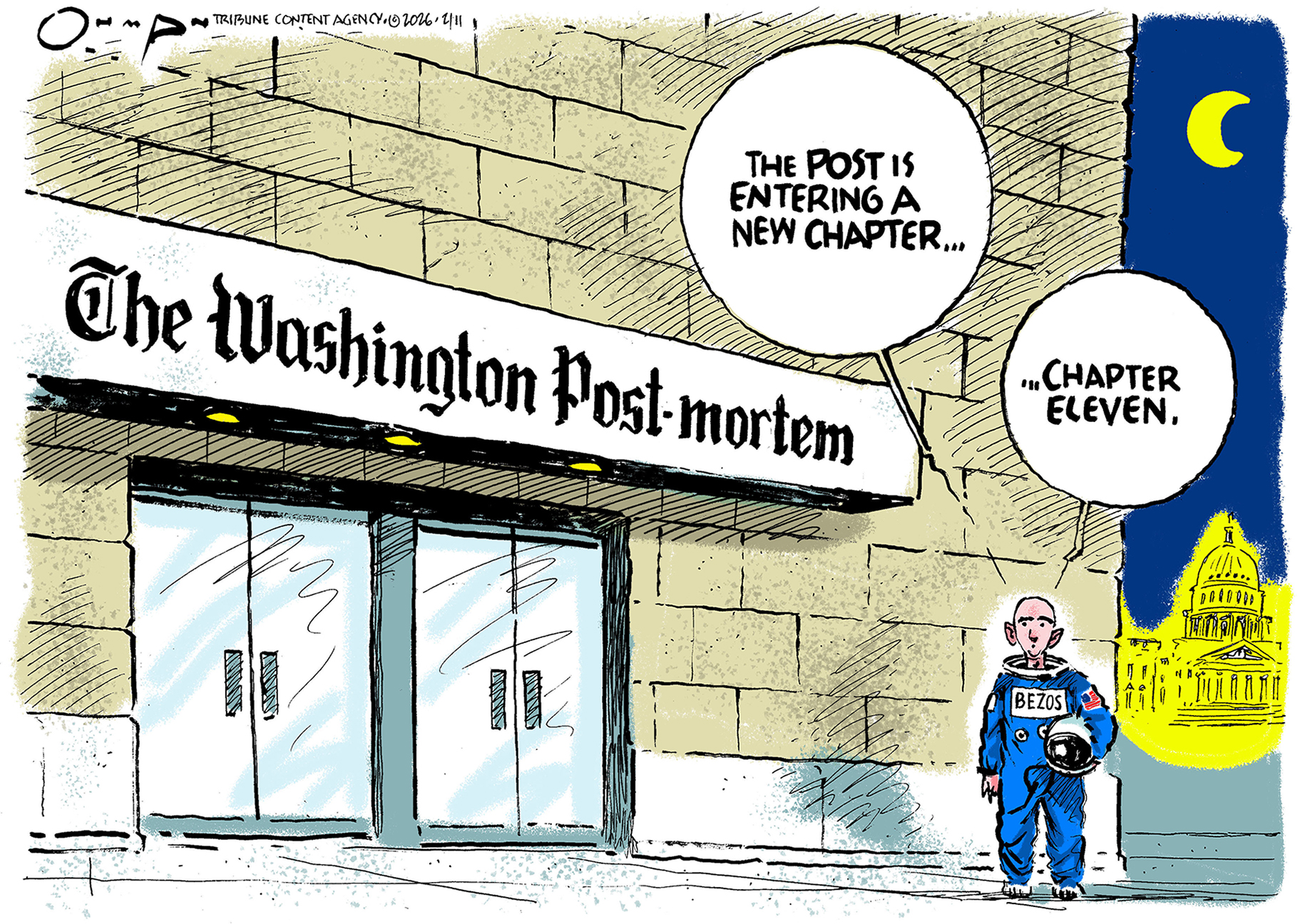

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffs

5 calamitous cartoons about the Washington Post layoffsCartoons Artists take on a new chapter in journalism, democracy in darkness, and more

-

Political cartoons for February 14

Political cartoons for February 14Cartoons Saturday's political cartoons include a Valentine's grift, Hillary on the hook, and more

-

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipe

Tourangelle-style pork with prunes recipeThe Week Recommends This traditional, rustic dish is a French classic

-

The 8 best superhero movies of all time

The 8 best superhero movies of all timethe week recommends A genre that now dominates studio filmmaking once struggled to get anyone to take it seriously

-

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TV

Heated Rivalry, Bridgerton and why sex still sells on TVTalking Point Gen Z – often stereotyped as prudish and puritanical – are attracted to authenticity

-

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’

Film reviews: ‘Send Help’ and ‘Private Life’Feature An office doormat is stranded alone with her awful boss and a frazzled therapist turns amateur murder investigator

-

February’s new movies include rehab facilities, 1990s Iraq and maybe an apocalypse

February’s new movies include rehab facilities, 1990s Iraq and maybe an apocalypsethe week recommends Time travelers, multiverse hoppers and an Iraqi parable highlight this month’s offerings during the depths of winter

-

The 8 best animated family movies of all time

The 8 best animated family movies of all timethe week recomends The best kids’ movies can make anything from the apocalypse to alien invasions seem like good, wholesome fun

-

Film reviews: ‘The Testament of Ann Lee,’ ’28 Years Later: The Bone Temple,’ and ‘Young Mothers’

Film reviews: ‘The Testament of Ann Lee,’ ’28 Years Later: The Bone Temple,’ and ‘Young Mothers’Feature A full-immersion portrait of the Shakers’ founder, a zombie virus brings out the best and worst in the human survivors, and pregnancy tests the resolve of four Belgian teenagers

-

The 8 best biopic movies of the 21st century (so far)

The 8 best biopic movies of the 21st century (so far)the week recommends Not all true stories are feel good tales, but the best biopics offer insight into broader social and political trends

-

Film review: ‘The Choral’

Film review: ‘The Choral’Feature Ralph Fiennes plays a demanding aesthete