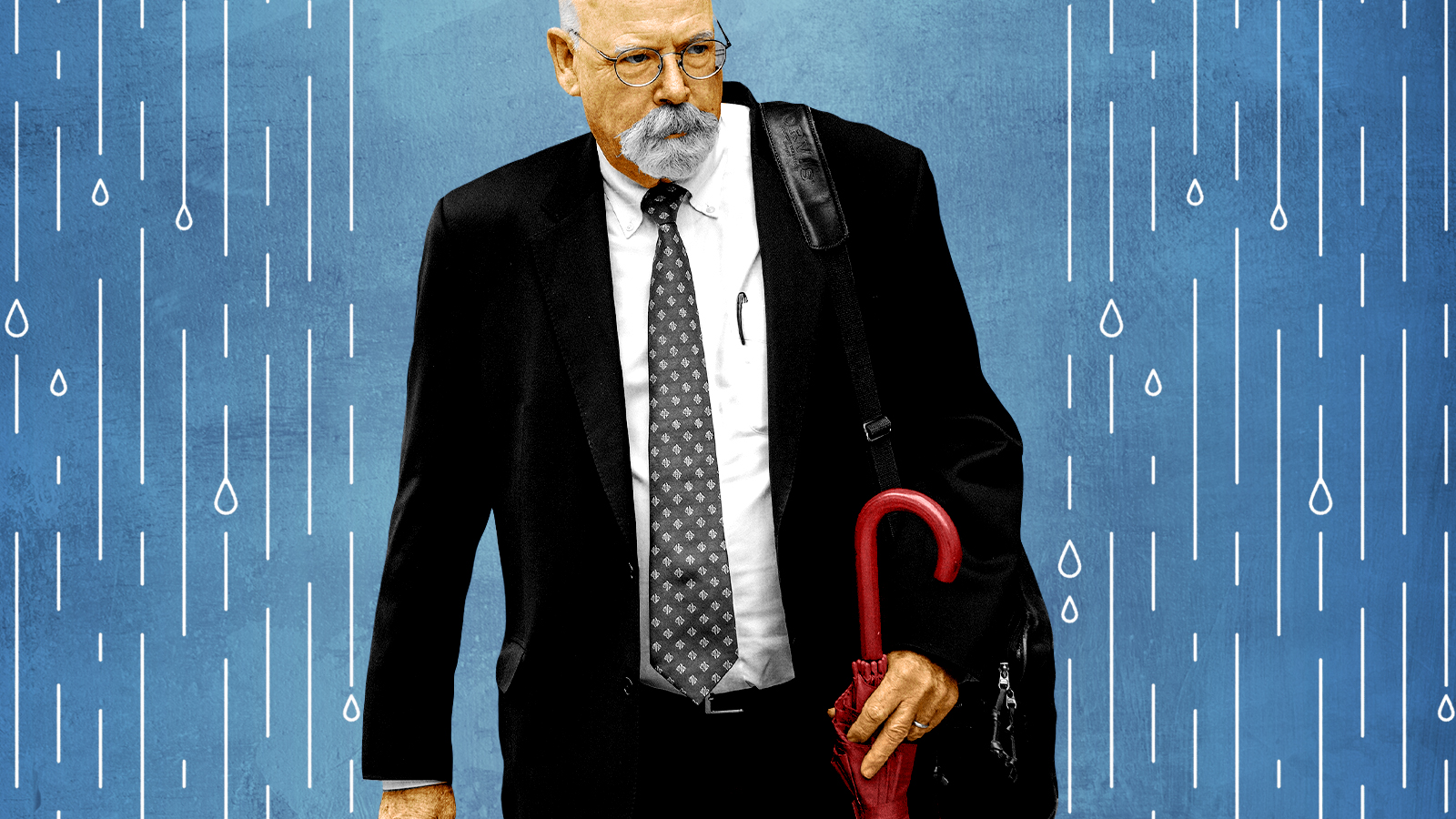

Special Counsel John Durham took his final loss. But did he fail?

Trump believed Durham would uncover 'the crime of the century.' This is what happened instead.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Special Counsel John Durham lost in court on Tuesday when a federal jury acquitted Igor Danchenko, a private researcher he had charged with five counts of lying to the FBI. It was Durham's second loss in the two trials he brought during his three-and-a-half years investigating the origins of the Justice Department's investigation of former President Donald Trump's campaign and its ties to Russia. It is also likely to be Durham's last case, and final loss, as special counsel.

"Trump and his supporters had long insisted the Durham inquiry would prove a 'deep state' conspiracy against him," The New York Times reports. "Trump predicted Durham would uncover 'the crime of the century' inside the U.S. law enforcement and intelligence agencies that investigated his campaign's links to Russia," The Washington Post adds. Instead, he secured a plea deal and 12 months of probation for an FBI lawyer who admitted to falsifying information to renew a secret surveillance warrant.

Here's a look back at what Durham was assigned to investigate, what he did investigate, and why he didn't find more:

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What was Durham's assignment?

William Barr, soon after Trump appointed him attorney general, ordered Durham, then the U.S. attorney in Connecticut, to review the origins of the Trump-Russia investigation. At that point, in May 2019, Durham's was the third active investigation of the FBI's Crossfire Hurricane counterintelligence investigation, along with inquiries by Justice Department Inspector General Michael Horowitz and by John Huber, the U.S. attorney in Utah.

By October 2019, Durham's administrative review had turned into a criminal investigation, though the Justice Department released no information on who or what crimes were being investigated. A month earlier, Barr and Durham had traveled to Italy to ask for the Italian government's help in the inquiry, and Barr also solicited assistance from Australia and Britain.

In December 2020, Barr announced he had upgraded Durham to special counsel right before the election, shielding him from political interference in case Trump lost. Barr's Oct. 19 order, obtained by The Associated Press, authorized Durham "to investigate whether any federal official, employee, or any person or entity violated the law in connection with the intelligence, counter-intelligence, or law enforcement activities" directed at the 2016 presidential campaigns or Trump administration officials.

Barr told AP that Durham's investigation began very broadly but had "narrowed considerably" and "really is focused on the activities of the Crossfire Hurricane investigation within the FBI."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

What has he accomplished as special counsel?

Durham's investigation has been shrouded in mystery since its inception, but his main public endeavors were the guilty plea for FBI lawyer Kevin Clinesmith and the unsuccessful prosecutions of Danchenko, a major source of information used by former British spy Christopher Steele in his largely discredited Trump-Russia dossier, and cybersecurity lawyer Michael Sussmann.

That may not seem like much, especially since the Horowitz investigation developed the case against Clinesmith.

But "Durham and his aides used the forum of the recent trials to air evidence of what they suggested was a failure by FBI personnel to pursue leads as they probed the sourcing of the Steele dossier," Politico's Josh Gerstein writes. "Durham's open criticism of the FBI produced an unusual spectacle at the trial, as he and his team attacked the competence of FBI agents and analysts who were the prosecution's key witnesses," but Durham's "disciples" see those salvos as "a silver lining in the veteran prosecutor's checkered courtroom record."

The Sussmann and Danchenko cases may have accomplished something else, too, the Times reports, citing Durham's crisis: "In pursuing charges, they damaged national security." In the latter case, especially, Durham's FBI witnesses said Danchenko had become a valuable paid informant whom FBI agents can no longer use because Barr effectively revealed his identity and Durham indicted him.

What's next in Durham's investigation?

"If Danchenko is indeed Durham's final criminal case, then his report will come next," The Washington Examiner reports. "The special counsel is reportedly working on finishing a lengthy set of findings laying out his investigation's conclusions, which will be handed over to Attorney General Merrick Garland," and Garland has testified he intends to release as much as possible to the public.

Durham has used his trials to portray his investigation as a kind of antidote to Special Counsel Robert Mueller's investigation of the Trump campaign's interactions with Russian election meddlers — though he misrepresented Mueller's findings in some cases. Barr released a redacted version of Mueller's final report; subsequent documents suggest Barr put his thumb on the scale in Trump's favor from the jump.

How does Durham's investigation compare to Mueller's?

Mueller accomplished much more than Durham in less time, but he had greater resources at his disposal and, presumably, better material to work with. Mueller turned in his final report 23 months after his appointment as special counsel, while Durham is now on the 42nd month of his investigation, according to a chart compiled by Marcy Wheeler.

While Durham charged three minor characters in the Trump-Russia saga and got one plea deal, Mueller charged 34 people — including top Trump aides Paul Manafort, Rick Gates, Roger Stone, and Michael Flynn — and three Russian companies. He obtained nine convictions or guilty pleas, and passed off to other prosecutors a handful of fruitful investigations that did not fit within his purview. Trump subsequently pardoned Manafort, Stone, Flynn, and Mueller prey George Papadopoulos, and Alex van der Zwaan.

Durham's investigation has cost taxpayers more than $5.8 million between October 2020 — when he was named special counsel, 18 months after his initial appointment to the case — and March 2022, the Justice Department reports.

Mueller's total investigation cost nearly $32 million, including Justice Department components that supported his office. He effectively returned much of that to the federal government through Manafort, who agreed to forfeit property in New York, funds in three bank accounts, and his life insurance policy, all valued at between $22 million and $42 million.

Did Durham fail?

That's a little subjective, and Durham still has his final report to make his case. But "simply put, federal prosecutors are not used to losing," Politico's Gerstein writes. "So, Durham's defeat at the Danchenko trial — which came less than five months after a similar acquittal in another case brought by the special prosecutor — represents an unmistakable defeat."

You can compare Durham's track record as special counsel against what had previously "been the highest-profile act of his career, when he led a special investigation of the CIA's Bush-era torture of terrorism detainees and destruction of videos of interrogation sessions," the Times reports. At that time, "Durham had set a high bar for charges and for releasing information related to the investigation. Throughout his 2008-2012 investigation, he found no one he deemed worthy of indictment even though two detainees had died in the CIA's custody, and he fought a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit to avoid disclosing to the public his findings and witness interview records."

Many people, having learned of Danchenko's acquittal, probably expressed "surprise that Durham was still going at all," while others were likely to shake their heads "and declare the probe a waste of time and money," David A. Graham writes at The Atlantic. These reactions "are correct, but they miss the point. Even if Durham approached the probe with earnest sincerity, the real reason he was appointed is that Donald Trump's political con requires the promise of total vindication right around the corner," and his investigation has already served that purpose.

"The hope for Trump supporters was that someone was going to crack open the case and show that the investigation was cooked up by Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton," maybe with help from George Soros and antifa, Graham elaborates. But Trump himself "recognized that the fact of an investigation was far more important than the results." It worked with Benghazi and Clinton's emails, and even earlier Trump-Russia counter-investigations, he adds. "By the time Trump was extorting Volodymyr Zelensky by withholding defense supplies in 2019, all Trump wanted was for Ukraine to announce an investigation into Hunter Biden. He didn't even care whether it actually happened, because the talking point is what he needed."

Peter has worked as a news and culture writer and editor at The Week since the site's launch in 2008. He covers politics, world affairs, religion and cultural currents. His journalism career began as a copy editor at a financial newswire and has included editorial positions at The New York Times Magazine, Facts on File, and Oregon State University.

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in Geneva

Witkoff and Kushner tackle Ukraine, Iran in GenevaSpeed Read Steve Witkoff and Jared Kushner held negotiations aimed at securing a nuclear deal with Iran and an end to Russia’s war in Ukraine

-

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House role

Kurt Olsen: Trump’s ‘Stop the Steal’ lawyer playing a major White House roleIn the Spotlight Olsen reportedly has access to significant US intelligence

-

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policy

Trump’s EPA kills legal basis for federal climate policySpeed Read The government’s authority to regulate several planet-warming pollutants has been repealed

-

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffs

House votes to end Trump’s Canada tariffsSpeed Read Six Republicans joined with Democrats to repeal the president’s tariffs

-

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearing

Bondi, Democrats clash over Epstein in hearingSpeed Read Attorney General Pam Bondi ignored survivors of convicted sex offender Jeffrey Epstein and demanded that Democrats apologize to Trump

-

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rolls

Judge blocks Trump suit for Michigan voter rollsSpeed Read A Trump-appointed federal judge rejected the administration’s demand for voters’ personal data

-

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train army

US to send 200 troops to Nigeria to train armySpeed Read Trump has accused the West African government of failing to protect Christians from terrorist attacks

-

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ video

Grand jury rejects charging 6 Democrats for ‘orders’ videoSpeed Read The jury refused to indict Democratic lawmakers for a video in which they urged military members to resist illegal orders