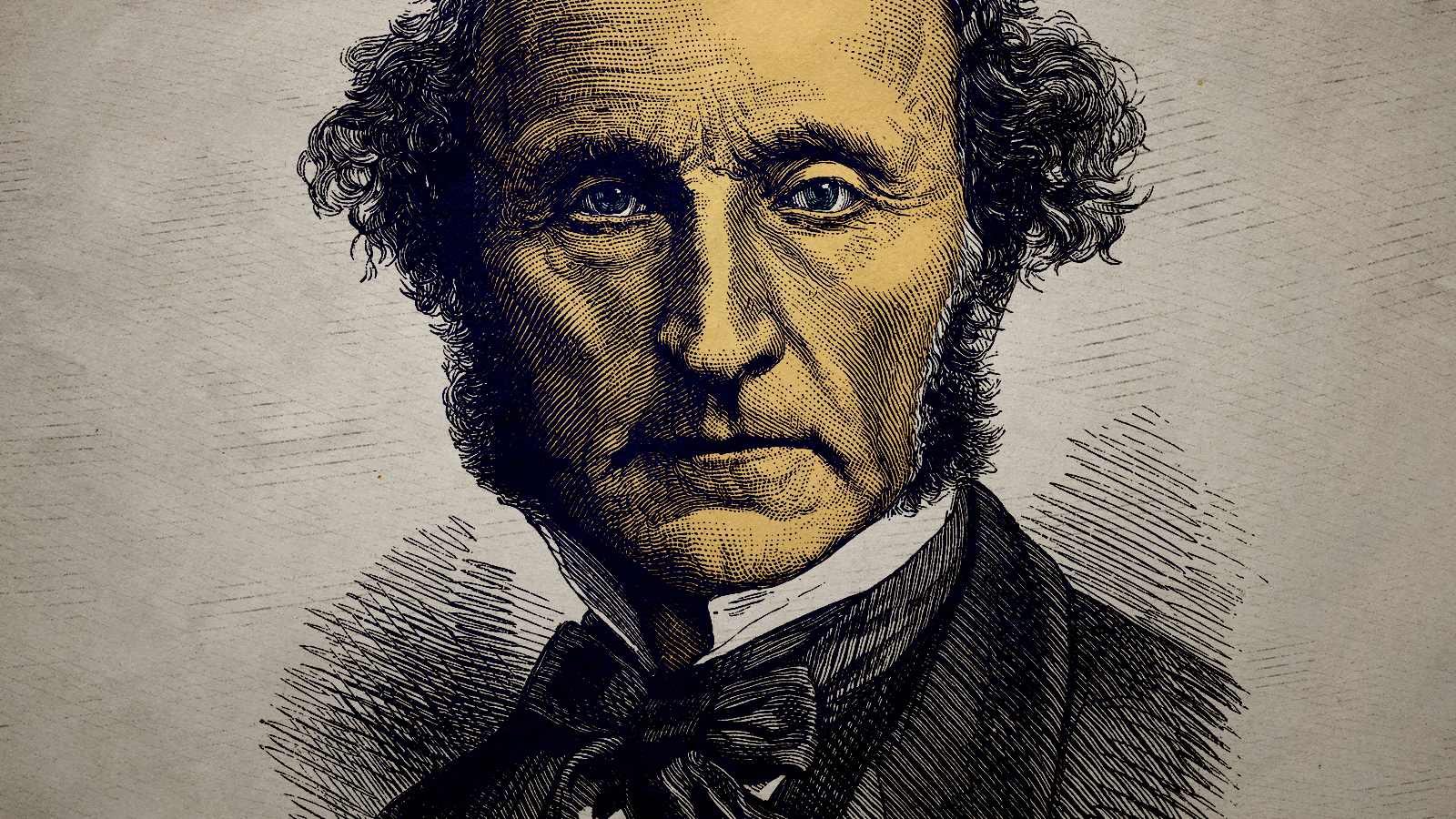

The thrill of teaching Mill

Free speech is a live issue again, and John Stuart Mill is an able guide

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

I used to dread teaching John Stuart Mill. A staple of introductory courses on political theory, On Liberty seemed more like a relic of Victorian conventionality than something relevant to the 21st century. Aristotle challenges students' assumptions about nature; Hobbes forces them to consider the connection between violence and order. But Mill? Who still needs his defense of a freedom to read and say what you like? Better to provoke students with his censorious antagonist, James Fitzjames Stephen.

I don't feel that way any more. The ubiquity of social media, coalescence of new taboos based on progressive theories of race and gender, and moralization of major institutions have rescued Mill from the syllabus of forgotten classics.

When I began teaching about 15 years ago, Mill's claim that the expression of bitterly contested and even deeply unpopular opinions should not only be permitted but encouraged seemed like a truism. Today, it is subject to debate, just as it was in Mill's day, when universities — at that time, often run by churches — were less hospitable to contested inquiry than were the press or political forums.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

But Mill's defense of liberty in "thought and discussion" isn't exactly what students expect — or what journalists and politicians often mean when discussing "free speech." In the first place, it's not primarily about the law. Even in the 19th century, Mill took for granted that legal constraints on what could be said or published were loose and ineffective, at least in "constitutional countries."

That assumption was wrong in the short term, as prosecutions of political, moral, and religious arguments continued to occur in Britain, the United States, and elsewhere during Mill's lifetime. In the long run, though, he accurately perceived the difficulty of justifying such restrictions in a nominally free society. Instead of targeting repressive laws, then, Mill focuses on social and cultural obstacles to dissent. "Our merely social intolerance kills no one, roots out no opinions," he wrote, "but induces men to disguise [their views], or to abstain from any active effort for their diffusion." Mill didn't use the phrase "cancel culture," but that's what he has in mind.

Mill's analysis is also limited to adults in full possession of their faculties. It doesn't include children, the mentally incompetent, or those with very little education. That qualification is important, if controversial, because it sets many of our present curriculum disputes to one side. While the proper content of K-12 instruction is open to disagreement, it's not what Mill's talking about. (The inevitability of such disputes made Mill skeptical of standardized government schooling, but that's a different story).

The one thing many people think they know about Mill is that he determines whether limitations of freedom are acceptable by means of the "harm principle." In On Liberty, Mill famously claims that "the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others."

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

If that sounds familiar, it's partly because the statement is memorably phrased and occurs in the first few paragraphs of the book. But it's also because the concept of harm has become a common justification for restrictions on speech and expression on the grounds that certain words, ideas, or arguments are damaging to some people exposed to them.

Despite the unfortunate similarity of terms, however, that's the opposite of Mill's position. "Harmful speech" is nearly inconceivable by his standards. To qualify as harm, Mill argues, an action must be directly connected to the negative consequence. Moreover, that consequence must be non-consensual, experienced by specific persons, and infringe of fundamental interests, including the liberty to make up one's own mind. By that standard, Mill concludes, it is impossible for speech to be harmful per se.

Mill doesn't deny that words or publications can have dangerous consequences, of course. He approves limits on threats, harassment, and incitement to violence. But most objections to words and ideas are based on offense, not concrete danger, and Mill insists on the distinction between the merely — if sometimes genuinely — offensive and the truly injurious.

More important, Mill maintains that the prevention of harm is a necessary condition of restraint, but not a sufficient one. The harm principle can be overridden if the regulation causes more harm than it prevents. Since the category of harm includes infringement of the freedom to consider a wide range of options and to make up one's own mind, the legal or social restraint of language and argument are hurtful to those from whom they take the opportunity to listen. Though Mill doesn't address the issue directly, his reasoning suggests that "deplatforming" or other seriously disruptive protests are inconsistent with freedom of thought and discussion.

One criticism of Mill that appears on the right as well as the left is it he appeals to a naive conception of neutrality. In other words, he seems to think all ideas compete fairly in a "marketplace of ideas." But market success can be influenced by advertising, incomplete information, or other forms of distortion, and indifference to the outcomes of discussion could leave society susceptible to political, moral, or other forms of corruption.

It's true some liberal theorists appeal to wide (though not absolute) neutrality among conceptions of justice and truth, but Mill is not among them. In ethics, he endorses a "Greek ideal of self-development" personified by the Athenian statesman Pericles. In epistemology, he assumes that as we strive to realize the ideal, "the number of doctrines which are no longer disputed or doubted will be constantly on the increase: and the well-being of mankind may almost be measured by the number and gravity of the truths which have reached the point of being uncontested." By forcing us to express the reasons for our beliefs to confront the possibility of error, Mill believes, unconstrained discussion not only brings us closer to truth but also makes us more capable of discerning truth when we find it.

These complications are important because they imply criteria for judging the "quality" of speech. High-value arguments promote the development of our faculties of judgment in pursuit of truth. Less worthy expressions ignore or hinders them. It's difficult to know in advance whether any particular idea serves a developmental purpose or not. But particular rhetorical tactics, including namecalling, accusations of bad faith, ad hominem attacks, or categorical dismissal of certain positions almost certainly won't.

Mill's argument has defects even on its own terms. For example, there's tension between Mill's confidence in progress and his insistence that objections should not be denied a hearing. Even if no one should be jailed or fired for believing that the Earth is flat, do their theories really deserve a hearing in physics courses? For all his relevance, Mill is quite old-fashioned in his assumption that moral and scientific improvement are mutually reinforcing.

Even harder to swallow is his support for the coercive improvement of undeveloped populations. Implicitly a defense of British rule in India, the claim is also open to reversal against Mill's own conclusions. If a moral and intellectual elite are entitled to coerce uncivilized foreigners for their own good, the objection goes, why not do the same to those deemed barbarians at home? The philosopher Herbert Marcuse used that ambiguity to make a case for "shifting the balance between right and left by restraining the liberty of the right." You don't have to believe cartoonish accounts of so-called cultural Marxism to worry Marcuse has more disciples, witting or unwitting, than Mill does these days.

For exactly that reason, though, teaching Mill has become exciting for the first time in my professional career. Once taken for granted, the purpose and extent of public expression and discussion is again a live issue, particularly in colleges struggling to combine intellectual freedom with conflicting demands that they promote economic opportunity, civic engagement, racial equality, mental health, and a litany of other purposes.

Mill doesn't tell us how to deal with the risk of viral notoriety, the sorites problem (in which individual expressions of criticism or objection add up to overwhelming disapproval), or the gender gap in tolerance for public disagreement. But for a serious conversation about the dilemmas of a liberal society, there's nowhere better to start.

More than 150 years ago, Mill wrote that "the practical question, where to place the limit — how to make the fitting adjustment between individual independence and social control — is a subject on which nearly everything remains to be done." The work is still not complete.

Samuel Goldman is a national correspondent at TheWeek.com. He is also an associate professor of political science at George Washington University, where he is executive director of the John L. Loeb, Jr. Institute for Religious Freedom and director of the Politics & Values Program. He received his Ph.D. from Harvard and was a postdoctoral fellow in Religion, Ethics, & Politics at Princeton University. His books include God's Country: Christian Zionism in America (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2018) and After Nationalism (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2021). In addition to academic research, Goldman's writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and many other publications.

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unity

Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl: A win for unityFeature The global superstar's halftime show was a celebration for everyone to enjoy

-

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?

The billionaires’ wealth tax: a catastrophe for California?Talking Point Peter Thiel and Larry Page preparing to change state residency

-

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one report

Bari Weiss’ ‘60 Minutes’ scandal is about more than one reportIN THE SPOTLIGHT By blocking an approved segment on a controversial prison holding US deportees in El Salvador, the editor-in-chief of CBS News has become the main story

-

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?

Has Zohran Mamdani shown the Democrats how to win again?Today’s Big Question New York City mayoral election touted as victory for left-wing populists but moderate centrist wins elsewhere present more complex path for Democratic Party

-

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ rallies

Millions turn out for anti-Trump ‘No Kings’ ralliesSpeed Read An estimated 7 million people participated, 2 million more than at the first ‘No Kings’ protest in June

-

Miami Freedom Tower’s MAGA library squeeze

Miami Freedom Tower’s MAGA library squeezeTHE EXPLAINER Plans to place Donald Trump’s presidential library next to an iconic symbol of Florida’s Cuban immigrant community has South Florida divided

-

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardon

Ghislaine Maxwell: angling for a Trump pardonTalking Point Convicted sex trafficker's testimony could shed new light on president's links to Jeffrey Epstein

-

The last words and final moments of 40 presidents

The last words and final moments of 40 presidentsThe Explainer Some are eloquent quotes worthy of the holders of the highest office in the nation, and others... aren't

-

The JFK files: the truth at last?

The JFK files: the truth at last?In The Spotlight More than 64,000 previously classified documents relating the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy have been released by the Trump administration