Are we excluding too many children from school?

Research shows school exclusion increases violent behaviour – so should we stop it?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

A growing number of local councils are pledging to reduce – or even stop – school exclusions, as studies highlight a link between excluded pupils, violent offences and a "pipeline to prison".

In the most recent study, focused on 40,000 teenagers with a history of behavioural difficulties and published in the British Journal of Criminology, researchers found that those who were permanently excluded from school were twice as likely to commit serious violence within a year as those who received a suspension.

"This new research provides evidence of what we have long known," Lib Peck, director of London's Violence Reduction Unit, told The Observer. "There is a clear link between children being excluded from school and involvement in violence."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

What did the commentators say?

A school pupil who is "acting out" may be facing "an unstable home environment, poverty, trauma, abuse" or mental health issues, educational psychologist Chris Bagley, research director of social enterprise States of Mind, said in The Bristol Cable. But instead of finding out why they are struggling, schools too often "dole out consequences" that can end in exclusion. This "ostracism" swiftly limits a student's "conception" of who they are and what they can be. They begin to believe they're "a 'bad kid' who can't learn and is destined for failure".

School exclusion also reinforces society's existing marginalisations, "disproportionately" affecting "poor children, those living in care, and children from Black Caribbean, mixed white Caribbean, and Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller backgrounds".

After a child is permanently excluded, they often end up in a Pupil Referral Unit, where a "tailored educational approach" is supposed to "provide them with a fresh start", special educational needs consultant Kate Grant wrote at East Anglia Bylines. But the curriculum is very "limited" and "the long-term psychological damage of rejection has already happened".

While campaigners are right to warn about the "pipeline from exclusion to prison", said Stephen Bush in the Financial Times, this issue is "more complicated than it first appears". After all, "is it really a surprise to discover" that the teenager who assaulted a fellow pupil or teacher is "the one who goes on to commit a violent criminal offence"?

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

And we must not forget that exclusion is "not just about the child who is made to leave school", but also about "the pupil who is not forced to attend the same institution as the teenager who physically assaulted them".

What next?

Limiting or stopping exclusions is an "extremely contentious issue," criminology professor Iain Brennan and epidemiologist Rosie Cornish, authors of the study published in The British Journal of Criminology, wrote at The Conversation. Many teachers and educationalists say "exclusions are necessary when a child's behaviour poses a threat to their classmates or teachers". But "allowing exclusion rates to keep rising risks letting down the most vulnerable and traumatised children".

The "warning signs" that can lead to a child's violence and exclusion "will have been clear in many cases". But, "too often, schools and teachers lack the time and resources to help" a child who is showing these signs. An "inclusive system" in which schools don't merely "respond to violence" but are empowered to "prevent it" would be a better solution than "disciplinary policies that may be doing more harm than good".

Chas Newkey-Burden has been part of The Week Digital team for more than a decade and a journalist for 25 years, starting out on the irreverent football weekly 90 Minutes, before moving to lifestyle magazines Loaded and Attitude. He was a columnist for The Big Issue and landed a world exclusive with David Beckham that became the weekly magazine’s bestselling issue. He now writes regularly for The Guardian, The Telegraph, The Independent, Metro, FourFourTwo and the i new site. He is also the author of a number of non-fiction books.

-

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?

Local elections 2026: where are they and who is expected to win?The Explainer Labour is braced for heavy losses and U-turn on postponing some council elections hasn’t helped the party’s prospects

-

6 of the world’s most accessible destinations

6 of the world’s most accessible destinationsThe Week Recommends Experience all of Berlin, Singapore and Sydney

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

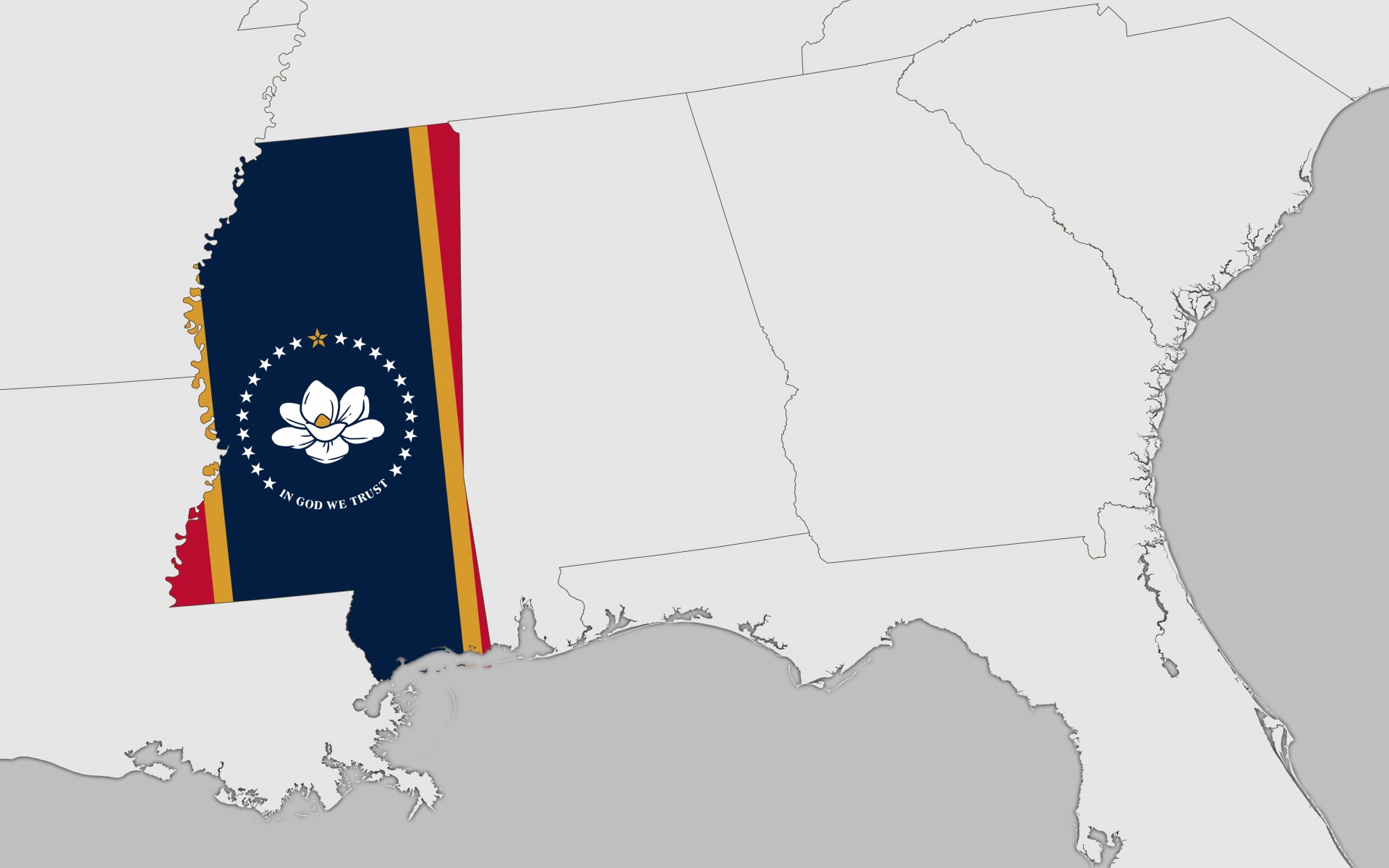

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in education

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in educationIn the Spotlight All eyes are on the Magnolia State

-

How will new V level qualifications work?

How will new V level qualifications work?The Explainer Government proposals aim to ‘streamline’ post-GCSE education options

-

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care system

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care systemIn the Spotlight A new report reveals that protection of youngsters in care in England is failing in a profit-chasing sector

-

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classrooms

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classroomsPros and cons The devices could be major distractions

-

School phone bans: Why they're spreading

School phone bans: Why they're spreadingFeature 17 states are imposing all-day phone bans in schools

-

Schools: The return of a dreaded fitness test

Schools: The return of a dreaded fitness testFeature Donald Trump is bringing the Presidential Fitness Test back to classrooms nationwide

-

Send reforms: government's battle over special educational needs

Send reforms: government's battle over special educational needsThe Explainer Current system in 'crisis' but parents fear overhaul will leave many young people behind