Spelling out why the 'science of reading' movement is winning the Reading Wars

Lawmakers across the US are being swayed

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

How we teach children to read has been a contentious issue in the United States for decades, a debate that has "occasionally grown so vicious it's been dubbed the Reading Wars," Vox reported. On one side are the proponents of the "science of reading" movement, a phonics- and cognitive-based instructional method. The opposing side champions "balanced literacy," emphasizing word recognition and context clues.

Policies have vacillated back and forth for over a century, but since 2019, the science of reading camp "has scored a victory that, if not permanent, is at least decisive," Vox pointed out. More than 40 states have passed laws during the past five years to reform reading instruction to be more aligned with cognitive research. Amid "an era of intense politicization of education," the push toward revamping reading instruction has garnered "rare bipartisan consensus," per The New York Times.

After years of back-and-forth, the tide is turning, and the science of reading movement is sweeping the nation.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The 'science of reading' vs 'balanced literacy'

The general philosophy of the science of reading is that "teaching strategies should align with a wide body of cognitive research on how young children learn to read," per the Times report. The strategies align with decades of research that shows that in addition to broadening their vocabulary, "children need to understand phonics, or the relationship between letters and the sounds of spoken language," the outlet added. Studies show that many students need "explicit, carefully sequenced instruction in the letter combinations and spelling patterns that form the English language." Without it, they may struggle to become competent readers. Leading brain researchers and parents of children with dyslexia have been among those pushing for more science-backed instruction.

The recent turn towards the "science of reading" contrasts with the balanced-literacy theories that heavily influenced how teachers were instructed to teach reading over the past two decades. Balanced literacy puts a greater emphasis on surrounding kids with books that interest them so they can spend classroom time quietly reading. Phonics instruction is still a part of this kind of teaching methodology but in a less structured manner. Instead of teaching phonics sequentially, teachers might discuss letter-sound relationships as they come up. Critics say balanced-literacy instruction often relies on discredited strategies that educators and researchers said "leaves children ill-prepared to tackle more difficult texts, without illustrations, as they get older."

How the science-backed movement took over

The wave of reading laws calling for more cognitive-based reading curricula "traces its roots to four main factors," Rachel Cohen wrote for Vox. It began five years ago with "an influential radio series" by the journalist Emily Hanford, which critically examined how popular teaching strategies in America contradicted existing neuroscience and cognitive psychology research about the best ways for kids to learn to read. Her reporting helped launch the "science of reading" movement.

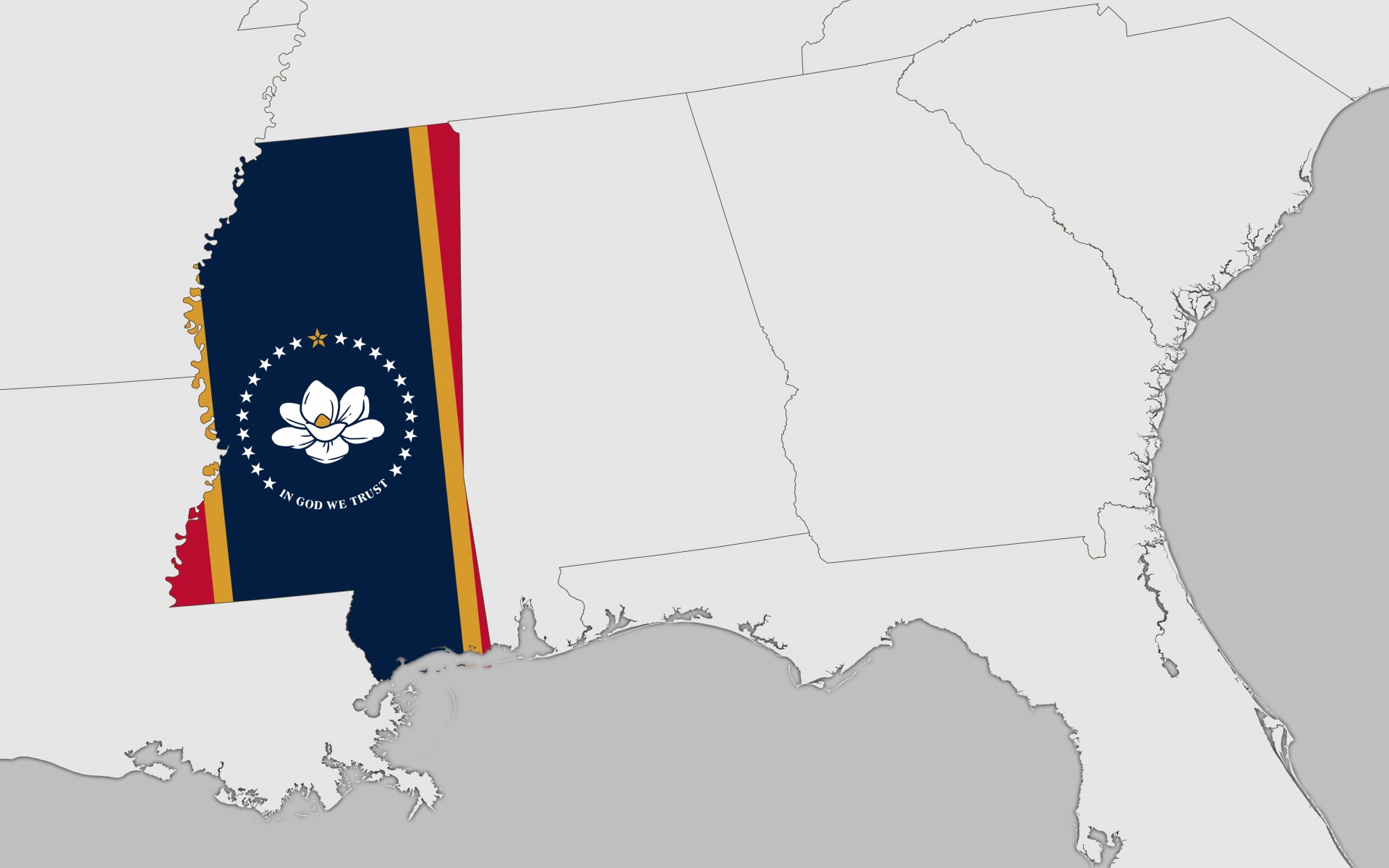

The second factor was when Mississippi's national test score rankings soared a year after a significant overhaul of the state's reading policies, including an embrace of the "science of reading." The third was "the emergence in the 2010s of national grassroots networks of parents of children with dyslexia," Cohen added. The parents have "brought their organizing prowess to bear for new state policies" that better suited their kid's needs.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

"And lastly, but no less important, was the pandemic, which fueled a major drop in student achievement and sparked an infusion of new federal funds for schools," she concluded.

Not everyone is on board with the shift toward cognitive research-based instruction. In the rush to recoup pandemic learning loss, schools are "scrambling in the wrong direction," Susan Engel, developmental psychology senior lecturer and founding director of the Program in Teaching at Williams College, and Catherine Snow, professor of cognition and education at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, wrote in a Washington Post op-ed. While fixating on teaching phonics to combat the loss, educators are "shortchanging something of equal importance: the role knowledge plays in helping children become good readers."

While correctly identifying sounds, letters, and words is critical for comprehension, "it is not enough," they opined. Students need to connect what they are reading to what they already know in order to be effective readers. "Unfortunately, U.S. schools emphasize decoding words over helping children acquire knowledge," they added.

Theara Coleman has worked as a staff writer at The Week since September 2022. She frequently writes about technology, education, literature and general news. She was previously a contributing writer and assistant editor at Honeysuckle Magazine, where she covered racial politics and cannabis industry news.

-

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 February

Quiz of The Week: 14 – 20 FebruaryQuiz Have you been paying attention to The Week’s news?

-

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?

The Week Unwrapped: Do the Freemasons have too much sway in the police force?Podcast Plus, what does the growing popularity of prediction markets mean for the future? And why are UK film and TV workers struggling?

-

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottages

Properties of the week: pretty thatched cottagesThe Week Recommends Featuring homes in West Sussex, Dorset and Suffolk

-

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterparts

American universities are losing ground to their foreign counterpartsThe Explainer While Harvard is still near the top, other colleges have slipped

-

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in education

How Mississippi moved from the bottom to the top in educationIn the Spotlight All eyes are on the Magnolia State

-

How will new V level qualifications work?

How will new V level qualifications work?The Explainer Government proposals aim to ‘streamline’ post-GCSE education options

-

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care system

England’s ‘dysfunctional’ children’s care systemIn the Spotlight A new report reveals that protection of youngsters in care in England is failing in a profit-chasing sector

-

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classrooms

The pros and cons of banning cellphones in classroomsPros and cons The devices could be major distractions

-

School phone bans: Why they're spreading

School phone bans: Why they're spreadingFeature 17 states are imposing all-day phone bans in schools

-

Education: America First vs. foreign students

Education: America First vs. foreign studentsFeature Trump's war on Harvard escalates as he blocks foreign students from enrolling at the university

-

Where will international students go if not the US?

Where will international students go if not the US?Talking Points China, Canada and the UK are ready to educate the world