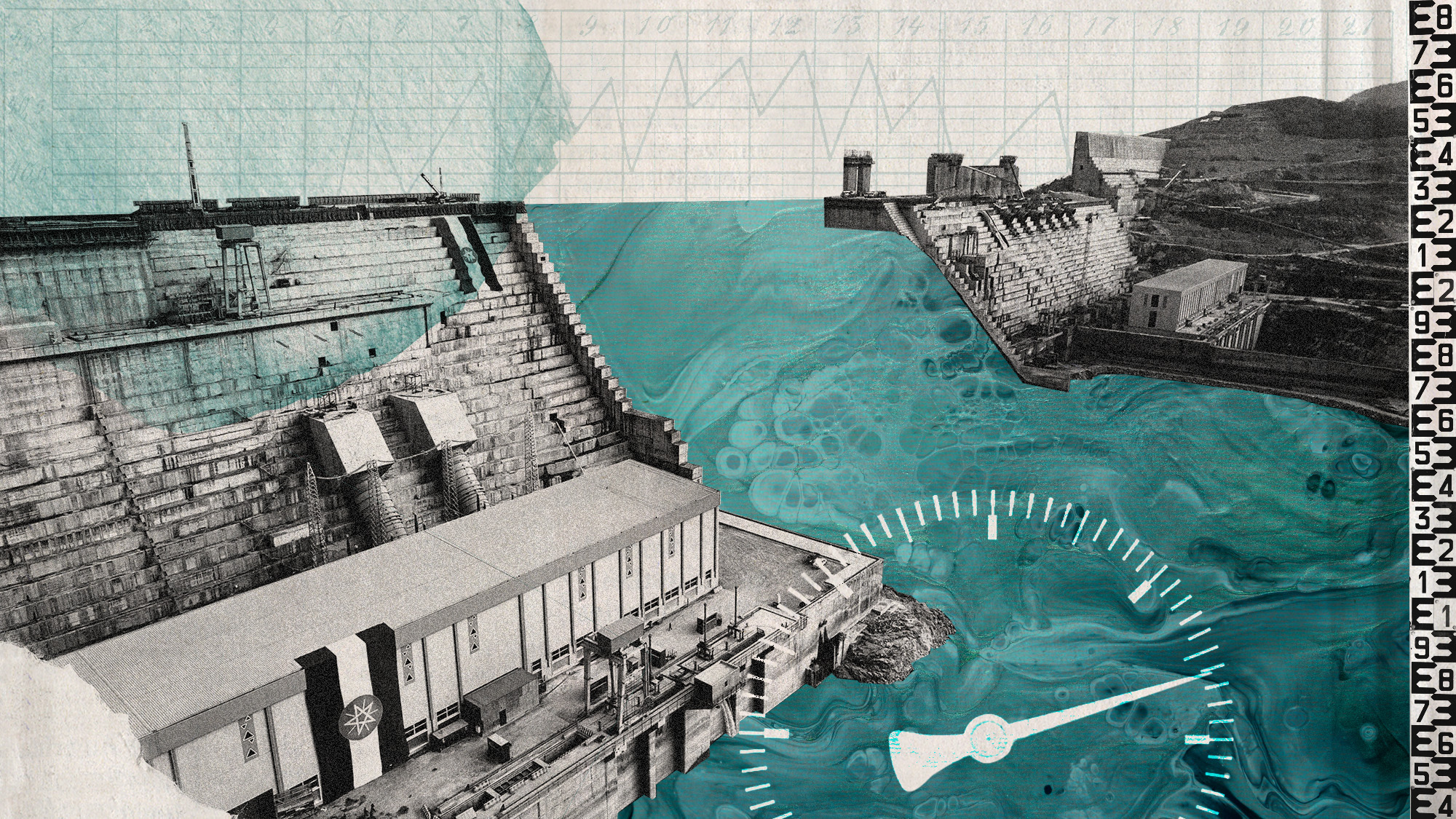

Africa's largest dam is making diplomatic waves

Ethiopians view using the Nile as a 'sovereign right' but the vast hydroelectric project has 'fuelled nationalist fervour' in Egypt and Sudan

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Ethiopians have celebrated the inauguration of Africa's largest dam as a defining moment in the country's history, even as downstream states warn of "grave consequences" without guarantees on how water flows will be managed.

Construction of the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam has "fuelled nationalist fervour in Egypt, which relies on the Nile for almost all of its water needs", said the Financial Times, but "also in Ethiopia, where use of the river is seen as a sovereign right".

'Energy hegemony'

Fourteen years in the making, the £3.7 billion dam built on the Blue Nile is more than a mile wide and 575 feet high. It is capable of holding back a reservoir covering an area roughly the size of Greater London.

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

For Ethiopians, Africa's largest hydroelectric plant is seen not just as a "pile of concrete in the middle of a river, but as a monument of their achievement", Moses Chrispus Okello, an analyst with the South Africa-based Institute for Security Studies think tank, told the BBC.

Members of the public have contributed to its financing through a series of crowdfunding campaigns, with the government also issuing bonds bought by companies and workers.

When fully operational the dam is expected to produce more than 5,000 megawatts of energy, enough to provide electricity for more than half of Ethiopia's 120 million people. It will also give the country "energy hegemony", help position Ethiopia as a major energy exporter in the region, and boost its foreign currency earnings, said Okello.

'Fuelling nationalist fervour'

For Egypt, "the dam represents the opposite of Ethiopia's hopes and ambitions", said the BBC.

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

In a country that relies almost entirely on the Nile for its water, there are "fears the dam could sharply reduce the flow of water to the country, causing water shortages".

For downstream states Egypt and Sudan, "the waters of the Blue Nile are vital" and already "increasingly scarce", said DW. A 2019 study published in the journal Earth's Future found that annual demand for water in the Nile Basin could regularly exceed supply by 2030.

Since Ethiopia began construction in 2011, Egypt and Sudan have "pushed for a legally binding deal to guarantee water flow, operational coordination and safety measures and a legal mechanism for resolving disputes", said DW. "But several attempts to reach an agreement over the years have failed."

Water experts in Egypt claim the dam has already "reduced the amount of water the country receives, and the government had to come up with short-term solutions such as reducing annual consumption and recycling irrigation water", said The Associated Press. "Sudanese experts say seasonal flooding has decreased during the dam's filling, but they warn that uncoordinated water releases could lead to sudden flooding or extended dry periods."

Ethiopia's Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed recently sought to downplay these concerns, stressing that the dam "is not a threat". However, it does mark a decisive break from the colonial-era deal negotiated by Britain in the 1920s that guaranteed Egypt around 80% of the Nile's water, as well as a 1959 bilateral treaty between Egypt and Sudan governing use of the river's resources.

"Britain did it to placate Egypt, and to secure its own interests because Egypt is a strategic state that controls the Suez Canal, the gateway to Europe," Rashid Abdi, an analyst at the Kenya-based Sahan Research think tank, told the BBC.

"But Ethiopia is now projecting power, while Egypt's fortunes have declined. It has lost its privileged status over the Nile."

-

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule works

How the FCC’s ‘equal time’ rule worksIn the Spotlight The law is at the heart of the Colbert-CBS conflict

-

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?

What is the endgame in the DHS shutdown?Today’s Big Question Democrats want to rein in ICE’s immigration crackdown

-

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’

‘Poor time management isn’t just an inconvenience’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Why broken water companies are failing England and Wales

Why broken water companies are failing England and WalesThe Explainer With rising bills, deteriorating river health and a lack of investment, regulators face an uphill battle to stabilise the industry

-

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’

The world is entering an ‘era of water bankruptcy’The explainer Water might soon be more valuable than gold

-

Taps could run dry in drought-stricken Tehran

Taps could run dry in drought-stricken TehranUnder the Radar President warns that unless rationing eases water crisis, citizens may have to evacuate the capital

-

The worst coral bleaching event breaks records

The worst coral bleaching event breaks recordsThe Explainer Bleaching has now affected 84% of the world's coral reefs

-

Anti-anxiety drug has a not-too-surprising effect on fish

Anti-anxiety drug has a not-too-surprising effect on fishUnder the radar The fish act bolder and take more risks

-

Thirteen missing after Red Sea tourist boat sinks

Thirteen missing after Red Sea tourist boat sinksSpeed Read The vessel sank near the Egyptian coastal town of Marsa Alam

-

Why the Earth's water cycle is under threat

Why the Earth's water cycle is under threatUnder The Radar Disturbances in the system that moves water around the world place more than half of global food production at risk

-

Why beaches are closing across the country

Why beaches are closing across the countryThe Explainer Step away from the water!