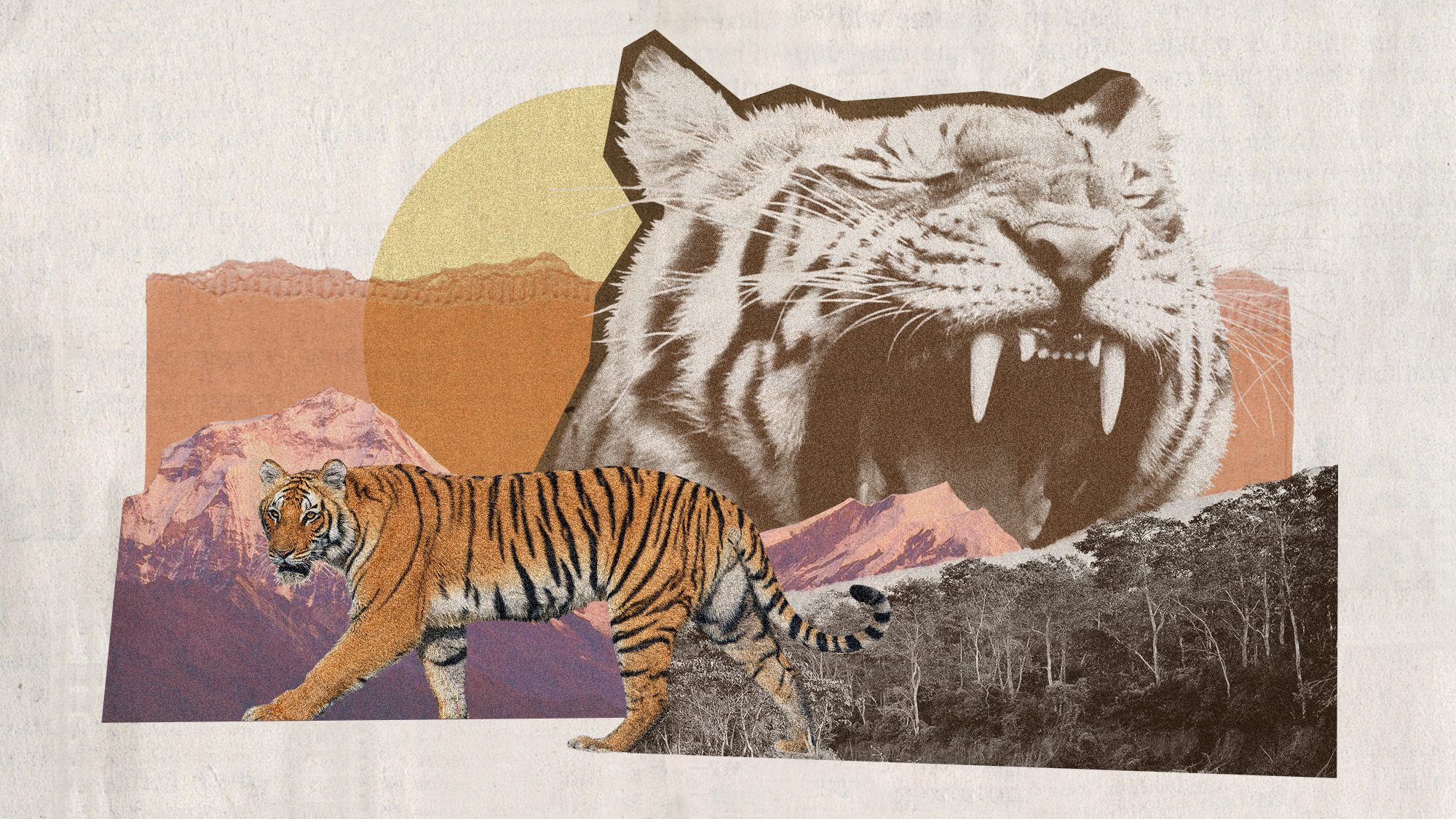

Does Nepal have too many tigers?

Numbers have tripled in a decade but conservation success comes with rise in human fatalities

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

For years conservationists hailed Nepal as a success after it tripled its wild tiger population in a decade.

Last year, the prime minister of the South Asian nation called tiger conservation "the pride of Nepal". But with fatal attacks on the rise, K.P. Sharma Oli has had a change of heart on the endangered animals: he says there are too many.

"In such a small country, we have more than 350 tigers," Oli said last month at an event reviewing Nepal's Cop29 achievements. "We can't have so many tigers and let them eat up humans."

The Week

Escape your echo chamber. Get the facts behind the news, plus analysis from multiple perspectives.

Sign up for The Week's Free Newsletters

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

From our morning news briefing to a weekly Good News Newsletter, get the best of The Week delivered directly to your inbox.

The success

A century ago, about 100,000 wild tigers roamed Asia. But thanks to rampant deforestation, poaching and trophy hunting their numbers plummeted. There are now only about 5,600 wild tigers left in 13 countries.

In 2010, those 13 nations met for a tiger summit in St Petersburg and committed to doubling their numbers by 2022: the Chinese year of the tiger. Nepal was the first to achieve that target, and to surpass it. Numbers rose from 121 in 2010 to 355 in 2022, thanks to a "strong government buy-in" for tiger conservation, expanded and heavily protected national parks, and strict anti-poaching laws, said National Geographic.

This "incredible feat" was "celebrated worldwide", said Al Jazeera, but the "roaring success" was accompanied by an "uncomfortable element in the room" – the "unfair, uncompensated burden" on local communities.

The cost

Fatal encounters are on the rise. Tigers killed nearly 40 people and injured 15 between 2019 and 2023, according to government data cited by the BBC, but locals say the true figure is "much higher".

A free daily email with the biggest news stories of the day – and the best features from TheWeek.com

Most attacks are happening in the "buffer zones" between national parks and human settlements. Locals often use them for cattle grazing or collecting firewood – but wildlife like tigers roam there, too. Forest corridors connecting different parks, allowing wildlife to pass between them freely, have become "yet another flashpoint". Locals who use them for foraging are "vulnerable".

Besides human fatalities, there are other costs, said Al Jazeera – "livestock losses, livelihood disruptions and plain fear".

Nepal's policy with tigers that attack humans was to put them in zoos – but each tiger costs about $50,000 per year to care for, plus $100,000 for the cage alone. The poor nation has stopped capturing "problematic tigers" because it "simply doesn't have the money".

The solutions

"For us, 150 tigers are enough," Oli said in December. "The tiger population should be proportionate to our forest area. Why not gift the extra tigers to other countries as economic diplomacy?"

And the prime minister isn't alone. In 2023, the then minister for forests and environment suggested auctioning tigers to trophy hunters. Birendra Mahato claimed Nepal could earn $25 million selling hunting licences. That "created widespread outrage as well as mockery from conservationists and environmentalists", said the Nepali Times, just as Oli's statement did last month.

Tigers are in fact "a major source of revenue": wildlife tourism and tiger safaris are a "big source of income" for communities near the national parks. An average of 3,000 people in Nepal are killed every year by venomous snakes, but "tiger kills get far more media attention".

Concern over the number of tigers is "misplaced", said tiger biologist Ullas Karanth. The issue is the number of prey animals: each tiger should be near about 500, he told the BBC. But humans are increasingly encroaching into tigers' habitats to cultivate the land, and reducing prey numbers, he said. Nepal should focus on "expanding protected areas" that have enough prey for the tigers.

For now, said the BBC, "the situation is at an impasse". It's unclear whether Oli's "tiger diplomacy" will gain traction, or who is to blame for the increased attacks – man or beast. But what is clear is that "humans and tigers are struggling to achieve peaceful coexistence".

Harriet Marsden is a senior staff writer and podcast panellist for The Week, covering world news and writing the weekly Global Digest newsletter. Before joining the site in 2023, she was a freelance journalist for seven years, working for The Guardian, The Times and The Independent among others, and regularly appearing on radio shows. In 2021, she was awarded the “journalist-at-large” fellowship by the Local Trust charity, and spent a year travelling independently to some of England’s most deprived areas to write about community activism. She has a master’s in international journalism from City University, and has also worked in Bolivia, Colombia and Spain.

-

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish minerals

The ‘ravenous’ demand for Cornish mineralsUnder the Radar Growing need for critical minerals to power tech has intensified ‘appetite’ for lithium, which could be a ‘huge boon’ for local economy

-

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?

Why are election experts taking Trump’s midterm threats seriously?IN THE SPOTLIGHT As the president muses about polling place deployments and a centralized electoral system aimed at one-party control, lawmakers are taking this administration at its word

-

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’

‘Restaurateurs have become millionaires’Instant Opinion Opinion, comment and editorials of the day

-

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’

Climate change could lead to a reptile ‘sexpocalypse’Under the radar The gender gap has hit the animal kingdom

-

Why the Middle East is obsessed with falcons

Why the Middle East is obsessed with falconsUnder the Radar Popularity of the birds of prey has been ‘soaring’ despite doubts over the legality of sourcing and concerns for animal welfare

-

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whales

How drones detected a deadly threat to Arctic whalesUnder the radar Monitoring the sea in the air

-

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming Arctic

‘Jumping genes’: how polar bears are rewiring their DNA to survive the warming ArcticUnder the radar The species is adapting to warmer temperatures

-

Death toll from Southeast Asia storms tops 1,000

Death toll from Southeast Asia storms tops 1,000speed read Catastrophic floods and landslides have struck Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia

-

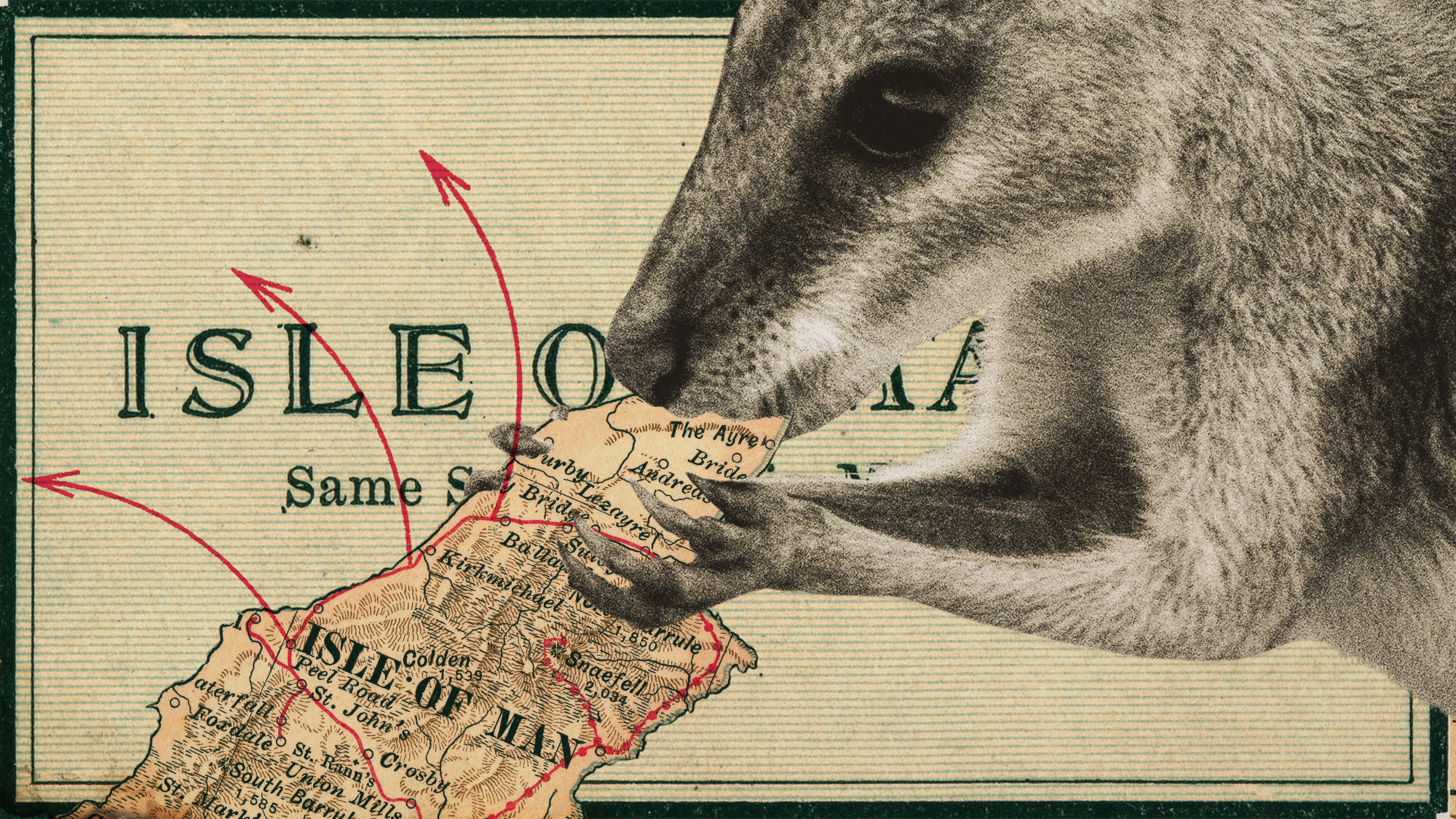

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’

The UK’s surprising ‘wallaby boom’Under the Radar The Australian marsupial has ‘colonised’ the Isle of Man and is now making regular appearances on the UK mainland

-

Taps could run dry in drought-stricken Tehran

Taps could run dry in drought-stricken TehranUnder the Radar President warns that unless rationing eases water crisis, citizens may have to evacuate the capital

-

The future of the Paris Agreement

The future of the Paris AgreementThe Explainer UN secretary general warns it is ‘inevitable’ the world will overshoot 1.5C target, but there is still time to change course